Morrison is the first Black woman to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

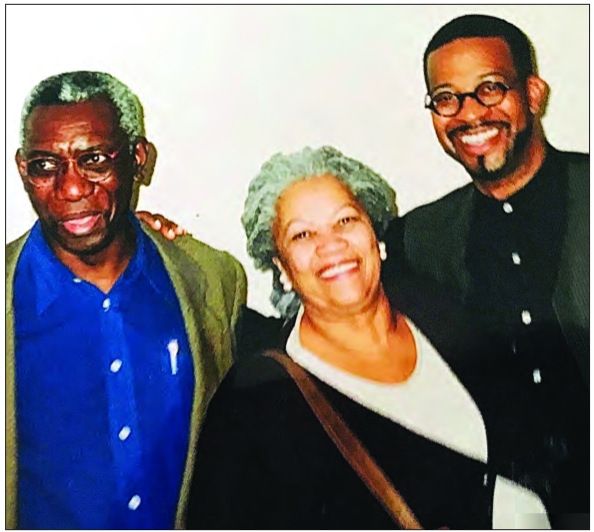

The author with Toni Morrison and American poet Yusef Komunyakaa

Photo of Morrison for the back cover of her debut novel, The Bluest Eye

“America became free, tested, tried, and triumphant, through that black pot experience.”

Of all the artists that I have come to understand as having a profound impact on arts, life, understanding our values, a sense of heritage and the powers particularly of literature, it’s Toni Morrison. She stands tall in the history of American literary arts as an author, writer, social critic, editor and spokesperson for humanities, education and culture.

With her elegant and powerful use of language and her gifted view into the world, she came to be a critical chronicler of our culture. Her role as a professor of literature at Princeton and her amazing career as a literary editor-turnedinternationally read and respected author, is legendary, unmatched in modern times. Few authors in our time enjoy iconic rock starlike public adoration. Her very presence, her words in response so thoughtful, informative, gracious and with critical bite.

Morrison’s collected work within the reflective realm creatively presents us with stories and characters whose actions and images point to social markers and symbols that reveal and recapture declarations that resonate with readers. These representations find some alignment with the values embodied in our literary heritages and the worthiness of her cultural expressions.

In her 2016 series of lectures at Harvard, collected in a book titled “The Origins of Others,” she uses the notion of “otherness” and takes the reader through numerous literature accounts, which illustrates the acuteness of social division due to a political prescription of “otherness” and provides a lens which is hugely disturbing to say the least. It is hardly a move toward a better society, as such suspicions and alienating our other sisters, brothers, neighbors and town dwellers we must avoid.

Morrison’s work gives us paths to recognize our failures and recover by telling stories in real terms through her characters.

Toni Morrison was born Chloe Ardelia Wofford on February 18, 1931, in Lorain, Ohio. She and her three brothers and sisters lived with their parents in the small Midwestern town along the Black River, integrated with many ethnicities.

It was called “the international city” because of its diverse population and being a major industrial center, with a shipyard and steel plants. Chloe’s father worked as a steel welder, her mom as a domestic. They were resourceful and respected members of a strong close-knit community. The area attracted many immigrants. These conditions were hugely impactful on Morison’s development as a person and thinker.

She learned to read at age three, and had heard their grandfather read the Bible five times. She came to understand that reading was “a revolutionary thing.” With the encouragement of her parents, she excelled in school. She studied Latin and read voraciously. As a child she worked in a library and spent more time reading the books than shelving them.

Chloe graduated with honors and attended Howard University in Washington, D.C. She graduated in 1953 with a bachelor’s degree in English and went on to graduate studies at Cornell University, receiving her master’s degree. Then she returned and taught at Howard from 1957 to 1964.

In 1958 she married Harold Morrison, a Jamaican architect, and had two sons. In 1965, Morrison began working as a textbook editor for a subsidiary of Random House in Syracuse, N.Y. Two years later she was recruited as an editor at Random House in New York City, where she worked for more than 15 years, being the first female African American editor in the company’s history.

Later, in a “second professional wind,” she began writing more steadily

as an author. She stated, “I look very hard for Black fiction because I

want to participate in developing a canon of Black work … where Black

people are talking to Black people.”

“The Bluest Eye,” her first

novel, was a book where Black girls were the centerpiece. Morrison

asks, “How does a child learn, self-loathing, and what are the

consequences? I won’t, I won’t be Black. I don’t want the Black one

(doll).” We remember those lines in the film “Imitation of Life.” This

is interior pain, so deep, that if the girls only had some

characteristic of the whiteness, she would be ok. That problematic

master narrative is imposed on everybody else.

The

central themes that define Morrison’s value sets as a writer are always

the Black American experience, as her characters find themselves and

their cultural identity. All this models a value system that’s end is to

find place, humanity and to celebrate the victories in the struggle to

assign meaning to a recognized humanity, in which love, struggle and

redemption are interwoven.

She

stated, “I knew words had power.” Toni Morrison, for our purposes here,

was a powerful leading champion of the arts and education.

“The

thought that leads me to contemplate with dread the erasure of other

voices, of unwritten novels, poems whispered or swallowed for fear of

being overheard by the wrong people, outlawed languages flourishing

underground, essayists’ questions challenging authority never being

posed, upstaged plays, canceled films — that thought is a nightmare. As

though a whole universe is being described in invisible ink.”

In

Black life and culture, arts, music, dance and very hugely books for

Black people have been, following the Bible, always held up and had an

incredible impact on our culture.

The

super prolific artist of words, ideas and concepts underlining our

human narratives, she wrote 11 novels, all of which are books she is

hugely known and celebrated for.

Morrison’s

work explores slavery, our history, gender influences, the lived

experiences of men and women, and celebrates Black American culture,

especially in music and geography, revealing the effects of generational

trauma particularly in regard to racism and sexism in families and the

larger community.

The

idea we raised about the total impact of artists’ ideas on value

construction and living is clear in the work of Toni Morrison. She

brought Black culture and literature into the previously exclusive world

of mainstream publishing. In Toni Morrison we have our griot.

Her

awards alone speak of the professional appreciation she garnered — the

1988 Pulitzer Prize for “Beloved,” National Book Critics Circle Award

for “Song of Solomon” and the 1993 Nobel Prize in Literature, making her

the first Black woman to be selected for the award. Toni Morrison

received as well the 2012 Presidential Medal of Freedom from Barack

Obama.

I love documentary films.

Toni

Morrison’s piece called, “The Pieces I Am,” softly fractured me, where I

am. I have never been so moved because it ripped questions through me

that I heard from her, and it showed up in my thinking about what we

might be now in the moment of now. So, what are you going to do? And

that question, for anyone, is riveting and compelling at once. Who am I

as I need to be now? I am not shy in sharing that as a younger man I

served as her 2001 Atelier visiting professor at Princeton, and she

commissioned an opera from me, on Black sculptress Edmonia Lewis.

She

helped me to not be fearful of failure, having anxieties, encouraging

not to focus on worry, noting that, “in the end, it’s about the results

of what you produce that really matters.” I’ve never forgotten that.

The

Pieces I Am film, more than any other, gives an account of not just a

person’s life, but how life can be understood through this person. That

person, the subject of the film, is Toni Morrison and understanding what

light she was.

Professor

Morrison credited her parents with instilling in her a love of reading,

music and folklore as they helped her develop a strong sense of clarity

and perspective.

In

the film, Oprah Winfrey notes, “Depth of meaning, knowledge and

education. ... There is not a sentence that does not teach us.”

The

film captures so many illuminating aspects of how Morrison was read and

respected by the general public, but in particular, her close

colleagues.

Morrison

in one segment states: “This is America, that is made from a melting

pot. All the people, are melting in the pot. Black people are the pot.

Everybody becomes melted together inside of us. Black people are the pot

that all got baked in because America became (free, tested, tried, and

triumphant) through that black pot experience.”

She

told TV journalist Charlie Rose, “If you can be tall because everyone

else is on their knees, what is tall? And who are you really?”

Near

the end of the film, Morrison states: “The older women I knew in my

family. …They were people of dignity and of value, and they knew they

had to pass that along.”

The

film closes as a loving postcard written by Morrison’s dear friend

poet, Sonya Sanchez. “And she was loved. To be human, to be alive and to

have done well on the planet and in the end someone saying, “you are

Beloved.”