The

Edgar P. Benjamin Healthcare Center on Mission Hill, shown March 6. In a

hearing July 31, Joseph Feaster announced Allaire Health Services as

his recommended bid for sale of ownership and operations of the Mission

Hill nursing home.

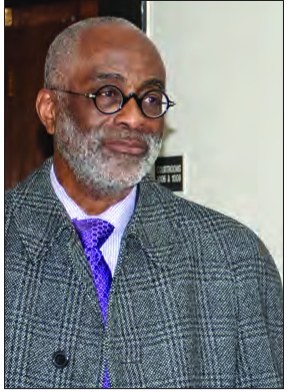

Joseph

Feaster, receiver for the Edgar P. Benjamin Healthcare Center, speaks

with staff following a Dec. 19 status conference in Suffolk County

Superior Court.

Receiver announces recommended bid in nursing facility buy-out

A pending sale of the Edgar P. Benjamin Healthcare Center took a step forward July 31 when Suffolk County Superior Court approved a suggestion by the facility’s receiver to sell ownership and operations to Allaire Health Service, a New-Jersey-based, for-profit operator of long-term care facilities.

The recommendation comes about four months after Joseph Feaster, the Mission Hill nursing home’s court-appointed receiver, first identified a sale as his suggested course of action to continue operations at the facility, and almost a year-and-a-half after Feaster was appointed by the court as receiver of the Edgar Benjamin. That move ousted former administrator Tony Francis amid a plan to close the center and allegations of financial mismanagement.

The receivership and commonwealth said they are seeking to close on the sale by the end of September. That timeline was endorsed by Superior Court Justice Anthony Campo, who presided over the status conference.

Feaster made his recommendation

of Allaire out of a field of seven bids received. He said that he,

along with the review team he put in place to consider the proposals,

narrowed the field to four — Allaire and local proposals from Mattapan

Community Development Corporation, TotalCare and a duo of physicians

including the Edgar Benjamin’s medical director, Dr. Kenya Hanspard.

The

review team, Feaster said, pushed the three local companies under

consideration to “buttress” their proposals by coming together to make a

joint venture, but the concept didn’t panned out.

In the end, he said, Allaire seemed best situated to take over operations of the facility.

“They

had the experience; they had the money; and while they’re not perfect,

they have, in my view, the right resume in order to be considered for

the position of the owner-operator,” Feaster said.

Allaire

Health Services, which was founded a decade ago, owns and operates 23

facilities in New Jersey, Pennsylvania and Vermont.

In

a document filed with the court on July 31 officially identifying his

recommendation, Feaster described Allaire as a company with a “strong

track record of transforming healthcare centers and has a history with

taking over distressed facilities and facilities in receivership.”

Allaire’s

$6.5 million bid includes an additional $2 million to $4 million for

renovations and an agreement to maintain the facility’s name and ensure

that no residents are displaced. Keeping the name and ensuring continued

operations as a long-term care facility were factors that Feaster

previously said were deal-breakers for him in pursuing a sale of the

center.

The company is

a for-profit organization, but despite a recent track record in

Massachusetts that includes companies like Steward Health Care — which

sold or closed its seven hospital campuses across the state during

bankruptcy proceedings last year — Feaster said that factor shouldn’t be

a disqualifying one.

“Everyone

seems to think not-for-profit is the nirvana of operation,” he said.

“Well, we have a notfor-profit and we’re a receivership right now, so I

don’t think that that’s necessarily the answer.”

The

sale process, he said, will have guardrails to try to encourage the

best outcomes for residents and the longevity of the facility, which

will be 100 years old in 2027.

Some

of those guardrails will come from the official processes that will

occur as the sale proceeds — the Department of Public Health will have

to provide approval as the licensing agency and the Public Charities

Division of the attorney general’s office will have input in the sale

from a nonprofit organization to a for-profit company.

But

Feaster said he’d also consider other possibilities like a deed

restriction or memorandum of understanding with his largest priority

being to ensure that the sale doesn’t lead to the facility being

shuttered and transformed into housing or other uses.

“The

process hasn’t ended,” Feaster said. “It’s really just beginning with

regards to moving towards that owner-operator consideration.”

In

recent months, the facility has faced ongoing financial challenges. The

center has had close calls with meeting payroll. In one instance,

Feaster said he had to pull $50,000 of his own money to close a gap.

Prior

to the receivership, under former Administrator Tony Francis’

leadership, the center repeatedly was unable to pay staff, a factor the

commonwealth cited as a reason it signed on, at the last minute, to the

suit that ousted Francis after months of declining to pursue a

receivership request against the center’s then-leadership.

And

a budget assembled by the center’s administrator Delicia Mark,

presented to the court in March, identified a $4 million shortfall by

the end of the year (in a report filed with the court in May, Feaster

said the facility performed better than expected, with the facility’s

total expenses clocking in about $284,000 lower than projected and total

revenue reaching about $162,000 more than forecasted).

Those

financial challenges come in part from outstanding debts and bills

leftover from the previous administration, which representatives from

the receivership said they hope will be knocked out by the pending sale.

Feaster

also said that it’s a matter of experience and operational factors,

too, pointing to Allaire’s more than 20 other facilities across the

Northeast.

“We have a

164-licensed-bed facility,” Feaster said. “Maybe this operator can get

closer to that number in the sense of the operation; that’ll keep the

revenue pieces in it. So, it’s not just throwing money at it; it’s

operating better as well.”

The

facility’s census has been a long-standing point of contention in the

court. At the time of the receivership, at the end of March 2024, the

facility had about 70 residents. As of May 2025 that number had risen to

79.

Throughout the

receivership process Feaster has butted heads with representatives from

the attorney general’s office and the state Department of Public Health,

who he alleged have failed to provide the appropriate support in

efforts to keep the facility operating.

The

state has argued that Feaster’s requests for advances on MassHealth

funding to support the facilities accounting costs, legal fees and

receivership costs oversteps what the state should or is able to

provide.

“The

commonwealth has paid more than $1 million,” said Assistant Attorney

General Mary Freeley at the conference, “it’s time to cut that off.”

The

ire was a pattern that continued in the July 31 status conference,

where Feaster and the receivership pushed for the state to advance more

funding to help the facility close gaps as it moves toward the buyout.

In

a document filed with the court on July 24, Feaster said the state

failed to provide court-approved advances from the start of the

receivership — April through December 2024 — when Campo ordered the

state to advance funds for legal fees and accounting and receivership

costs.

Superior Court Justice Christopher Belezos later paused that order in March.

The state has paid advances for the three-month period during which the order was active.

At

the July 31 status conference, Campo said that his December order

applied from then through March, when it was paused, and didn’t compel

the state to provide the funding Feaster requested from that spring

through December.

Disagreements

between Feaster and the state were a point of frustration for Belezos

while he presided over the case throughout the spring and continue to be

for Campo, who suggested the two parties could communicate better.

“It’s

not kumbaya, it’s just sharing information,” Campo said during the

status conference. “You don’t have to hug it out, just share

information.”