(Top)

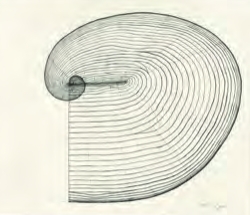

“Untitled,” c. 2003, graphite on paper; (Above) “Big Phrygian,” 2010 –

2014, painted red cedar, Glenstone Museum, courtesy the artist and

Matthew Marks Gallery. © Martin Puryear, courtesy Museum of Fine Arts,

Boston; (Left) “Confessional,” 1996 – 2000, Wire mesh, staples, nails,

steel rods, tar, various woods, © Martin Puryear PHOTO: ©MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON Interpreting the natural world through organic materials and exquisite craftsmanship

“Martin Puryear: Nexus” is the first sizable survey of the artist in almost two decades. Produced by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in collaboration with the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA), the large-scale installation showcases the sculptor’s masterful manipulation of materials.

More than 50 works from throughout Puryear’s career showcase his craftsmanship with wood, glass, marble, metal and leather, which is carefully manipulated into curves and latticework.

The natural world of plants and animals, particularly birds, are a consistent theme throughout the exhibition. Puryear uses a vast swath of materials but always comes back to wood; visitors can see across the span of his career how his work with cedar and poplar has evolved.

“He’s interested in everything from African architecture and artifacts to Scandinavian woodworking,” said Ian Alteveer, Beal Family Chair of the Department of Contemporary Art. “Everything from weaving baskets to building ships to making barrels and all of that comes through in the ways in which his work takes shape.”

Puryear also pulls on history and culture in his work. A series of worked rawhide strips lined up like a musical composition or a paragraph of text is titled “Some Lines for Jim Beckwourth.” Beckwourth was a multiracial trapper, rancher and entrepreneur who was born into slavery in Virginia in 1798. Puryear cleaned, dried and worked the rawhide himself just as Beckwourth might have in his travels.

In addition to the

sculptures Puryear is best known for, several works on paper are

displayed, some preparatory drawings juxtaposed with the finished pieces

and some more abstract etchings and aquatints. In both his large-scale

sculptures and two-dimensional works,

Puryear often comes back to curves. He crafts woods into seamless loops

and circles that look as effortless as the lines drawn on the page.

Alteveer

says there are also opportunities to connect Puryear’s work to the

museum’s collection. The gyrfalcon [a bird of prey] was a fascination of

Puryear’s and falcons can be seen throughout the exhibition. Alteveer

says Puryear loved to look at a Mughal miniature painting [a South Asian

painting style developed the Mughal Empire territory of the Indian

subcontinent] in the MFA’s collection. The painting, from 1619, depicts a

gift of a falcon to a Mughal emperor. Puryear has a reproduction of the

piece in his studio.

Here,

visitors to the exhibition can see a link between Puryear’s work and

centuries of art history, as well as a connection between Puryear and

the Boston collection specifically. This format, of presenting major

contemporary artists in Boston against the backdrop of art history, is

one that Alteveer hopes to continue in the contemporary department.

“Martin

Puryear: Nexus” will run at the MFA through Feb. 8, 2026. From there it

will travel to the Cleveland Museum of Art and the High Museum of Art

in Atlanta.

Alteveer encourages art lovers to visit the show; pictures just can’t do the works justice.

“It’s

a very physical experience to view Martin’s work, because you have to

walk around it, you have to see it in person to experience its forms and

its textures,” Alteveer said. “In person, the objects are just

fantastic to behold.”

ON THE WEB

Learn more at mfa.org