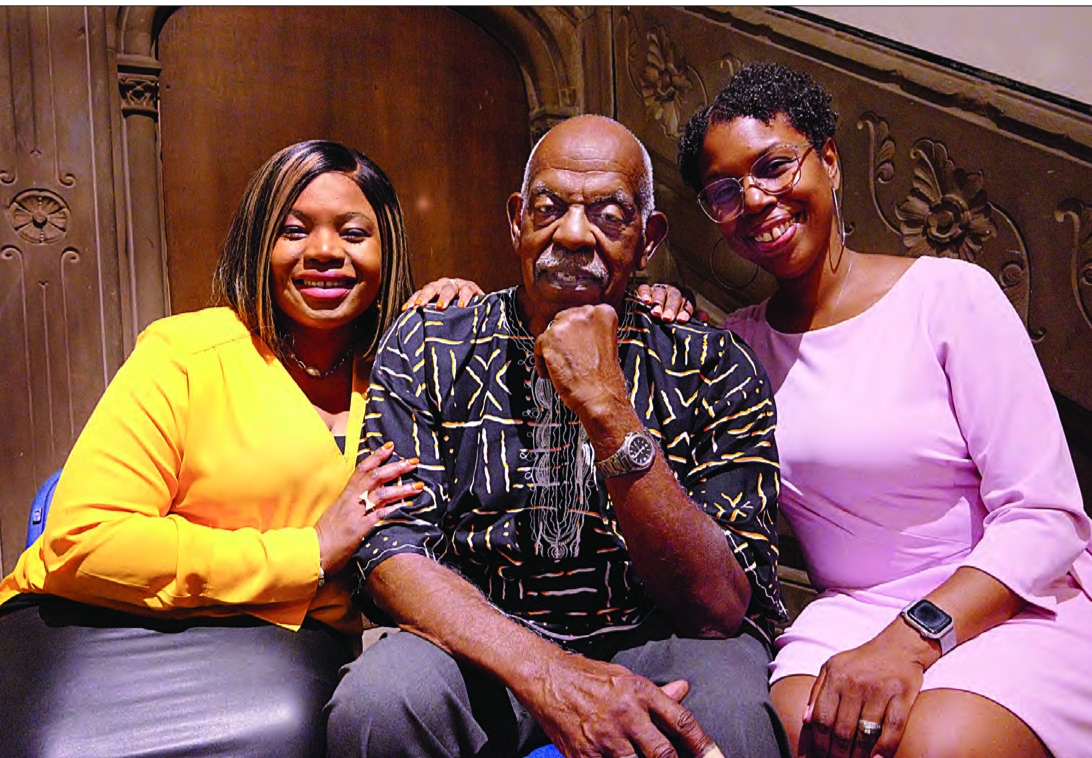

Barry Gaither (center), longtime executive director of the National Center of Afro-American Artists, is handing the reins to Akiba Abaka (left). At right is Kafi Meadows, co-chair of the center’s board.

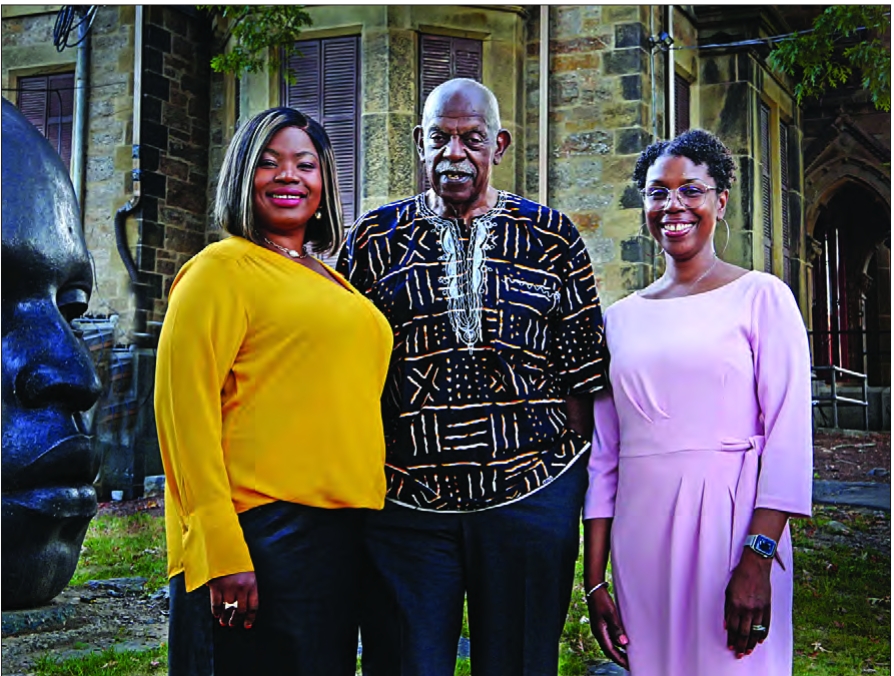

Dr. Barry Gaither (center) stands in front of the National Center of Afro-American Artists building with the new executive director Akiba Abaka (left) and Kafi Meadows, NCAAA board co-chair.

Barry Gaither steps down after half century at NCAAA helm

Roxbury’s premier Black cultural institution is undergoing a leadership change, with Barry Gaither stepping down as the longtime executive director of the National Center of Afro-American Artists founded by Elma Lewis.

Akiba Abaka, a theater producer and arts administrator, succeeds him as director of the center best known for its museum in a historic mansion and Christmastime production of “Black Nativity,” a play by Langston Hughes.

The transition, which began in the summer, was announced Sept. 24. Gaither, whom Lewis recruited in 1969 to create the art museum, will remain affiliated with the National Center of Afro-American Artists as executive director emeritus.

“I dedicated my life to the NCAAA and the work of Black artists because I believe deeply in the power of art to affirm the dignity, creativity and contributions of Black people everywhere,” Gaither, 80, said. “It’s been my life’s honor to build upon the foundation laid by my friend Elma Lewis and to foster a home here for Black artists.”

Gaither said he urged the center’s board to hire Abaka, 45, who he has known for about 15 years.

“We didn’t do a formal search. She was handpicked,” said Kafi Meadows, co-chair of the center’s board and a greatniece of Lewis.

Abaka will continue as interim executive director on a part-time basis while continuing to teach at the Orchard Gardens School in Roxbury. Meadows said the board plans to make her position permanent and full time after a fundraising campaign.

“I feel that I have been preparing for this role my entire career.

I’m knowledgeable and experienced in arts management, on all levels, as a technician, artist and as an executive,” Abaka said. “It is very rare to fall in succession to the dreams of your heroes. Miss Lewis was my hero. Mister Gaither is my hero.”

The center’s underappreciated museum, housed in the former Abbotsford mansion on Walnut Avenue, features a permanent installation on a Nubian king of ancient Egypt and an outdoor sculpture by John Wilson, “Eternal Presence,” commonly known as the “Big Head” statue. The museum’s extensive collection of Black art includes works by Romare Bearden, Charles White, Elizabeth Catlett, Jacob Lawrence and Allan Crite, the late South End artist.

“Black Nativity” is scheduled to begin its 55th run of performances in December. The center says it is “the longest running production” of the play in the world.

As a creative producer with Emerson College, Abaka in 2014 orchestrated the move of the play, which has been always staged downtown, to the college’s Paramount Center in the theater district.

Chuckling, Abaka said, “You know, sometimes it’s good to be a gatekeeper because sometimes you get to open the gates. It’s not just about blocking people. It’s about letting people in. That’s one of the proudest moments of my career.”

Abaka, a Jamaican immigrant, graduated from UMass Boston and holds a master’s in theater production and applied theater from Emerson.

Her experience curating stage performances, she said, translates to doing the same with visual arts in the center’s museum.

“My practice is curation,” Abaka said. “While my (past) work isn’t about putting art on display in the way of fine arts, it is putting stories on display.”

Meadows, a product manager at a life sciences company, noted that the center encompasses more than the visual arts.

“NCAAA is not just a museum.

It does both visual and performing arts,” she said. “Because we have a physical museum, a lot of times we are thought of as only a museum.”

Meadows said the board has given Abaka a charge that includes increasing the center’s visibility and raising $10 million in three years to “build out” visual and performing arts and grow the staff in phases, with department heads. That fundraising would also support a full-time salary for Abaka.

“We have cultivated some very strong relationships over time, but we don’t ask very much. We give a lot,” Abaka said. “So, I’m coming around with my hat. There’s going to be a lot of asking.”

Abaka said naming rights for the museum’s grounds and gallery spaces will be one of her fundraising strategies.

“That is a standard practice across the field. If you go to many of our neighboring art museums, there’s a name everywhere. I went to a suite of toilets at a neighboring art venue, and the toilets had names on them,” she said with a laugh.

Gaither said in recent years a new, million-dollar roof was installed on the museum, where overhead for utilities and insurance policies runs about $25,000 a year. He had hoped to put the center on firmer financial footing by building a new museum alongside commercial properties on Parcel 3 in the Southwest Corridor to provide “unrelated earned income.” But after years of planning, the center lost the development rights in 2023.

“I spent almost a year avoiding driving past that site, it was so painful to me,” he said.

Gaither, a South Carolina native who graduated from Morehouse College and earned a master’s in art history from Brown University, is known for giving insightful, elevating talks about works of Black art. For years, he has run the center and its museum largely by himself, with help from community volunteers, including members of the center’s working board.

During an interview in one of the museum’s galleries, Gaither expressed disappointment that wealthy Black individuals have not donated more to the museum.

“I am neither happy nor satisfied that what stands now represents fairly a good product for 52 years. I had in mind that we would by now have come to a place with much more solid support from our own community, in terms of endowing the support of our legacy,” he said.

Gaither added: “So that is a disappointment. I hope that it is not a terminal disappointment.”

He also expressed satisfaction that the works of some Black artists he championed for decades have at last been put on permanent display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where he served as a consultant.

The news release announcing the leadership change does not include any form of the word “retire.”

“I’m not sure Barry is going anywhere. It would be excellent to keep him in our hemisphere,” Meadows said.

Gaither said he plans to spend time assessing the 3,500 items in the museum’s collections, including 400 sketches, drawings, prints and completed and unfinished works by Crite. “We hold a really valuable view into his works,” Gaither said.

He said he looks forward to being able to “travel and write and rest. I’m going to do my best to see if I can accomplish that. But to accomplish that, new generations have to pick this up and move it forward.”

Gaither expressed “my undying confidence” in Abaka. “She’s a hard worker, she’s a visionary, and she knows important pieces of that artistic environment that I don’t. I never knew the theater world here nothing like she does,” he said.

Vivian Johnson, the retired Boston University professor who co-chairs the board with Meadows, said the generational transition “represents continuing growth and development” in the center and its programs.