(above)

Maquette for ‘Eternal Presence,’ William Francis Warden Fund, © Estate

of John Wilson; (right) Roz No. 9, Study for Eternal Presence, Virginia

Herrick Deknatel Purchase Fund and Lee M. Friedman Fund, © Estate of

John Wilson

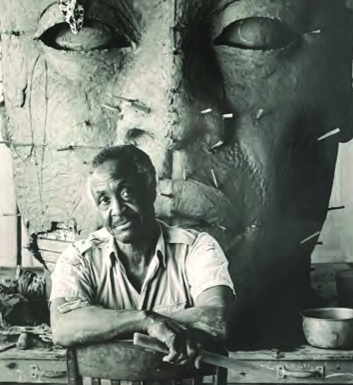

Wilson with the clay for Eternal Presence, John Wilson Archive.

The largest ever exhibition of John Wilson’s work opens at the Museum of Fine Arts

Artist John Wilson, the sculptor behind “Eternal Presence” at the National Center for Afro-American Artists, has been a revered artistic figure in Roxbury for decades. A new exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts aims to showcase Wilson’s talent on a national scale. “Witnessing Humanity: The Art of John Wilson” is the largest exhibition of his work.

“He is very much a presence within Boston, and one of the things which really framed the whole exhibition was our absolute conviction that Wilson needed to be much better known on the national platform,” said co-curator Edward Saywell, the MFA’s chair of prints and drawings.

Wilson was born in Roxbury in 1922 and won a coveted scholarship to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. He traveled abroad in Paris and Mexico and lived with his family in Chicago and New York before returning in 1964 to Boston, where he would teach drawing at Boston University for 20 years. Wilson was deeply immersed in the local arts scene, in particular with the Elma Lewis School of Fine Arts and the National Center of Afro-American Artists (NCAAA) in Roxbury.

Saywell curated the exhibition in tandem with Patrick Murphy, the MFA’s Lia and William Poorvu Curator of Prints and Drawings; Leslie King Hammond, art historian, professor emerita and founding director for the Center for Race and Culture at Maryland Institute College of Art; and Jennifer Farrell, the Jordan Schnitzer Curator in the Department of Drawings and Prints at the Met.

They consulted a number of local artists, educators and historians as well, including Constanza Alarcón Tennen, D. McMillion-Williams, Jabari Asim, Jamal Thorne, Jeffrey Nowlin, Paula C. Austin, Silvia Lopez Chavez, Tito Jackson and Zaria Karakashian-Jones and Edmund Barry Gaither, the director and curator of the Museum of the NCAAA, who has championed Wilson’s work for decades.

A maquette for “Eternal Presence,” colloquially referred to as “The Big Head,” anchors the exhibition. From the moment art lovers step into the show they can see the strong bronze profile, one of Wilson’s bestknown works and a powerful connector to his native Roxbury.

Some 110 works are on display in the exhibition, ranging from drawings, prints and sculptures to examples of Wilson’s sketchbooks.

Wilson’s work was remarkably consistent throughout his 60-year career. His work centered on social justice issues, particularly the violence and racism targeted toward Black Americans. He both depicted and criticized that

societal bent, while creating the dignified, beautiful portraits of

Black figures that he couldn’t find in the art historical canon.

“One

of the incredibly powerful things that we see in Wilson’s work is this

thread from his very earliest work all the way through to his last works

in which he is so focused on issues of racial injustice, economic

precarity and a whole host of other social justice issues,” said

Saywell.

The artist is

perhaps best known for his portraits in which the subject often engages

directly with the viewer, reclaiming power and demanding to be

recognized as humans worthy of dignity and respect.

In

“Streetcar Scene,” a lithograph drafted in 1945, a Black gentleman sits

on a streetcar crowded with white patrons. Here he reflects on the

anxieties of the war in Europe as a Black American. The figure stares

out directly at the viewer.

In

the same room as “Eternal Presence,” viewers will see a series of

large-scale portraits from Wilson’s 1970s “Young Americans” series.

These are portraits of Wilson’s children, their friends and other

associates of the family. Though these are made differently, on a large

scale using colored crayon and charcoal on paper, the figures engage

with the viewers in the same way, 30 years into Wilson’s career.

But Wilson did not shy away from confronting the horrors of racial injustice.

During

his time in Mexico he painted “The Incident,” a 1952 mural (now

destroyed) depicting a Black family watching a lynching through their

window. The terrified mother shields a small baby while the father

figure holds a gun and looks on angrily.

A

number of works related to “The Incident” are on view in the

exhibition. It is one of Wilson’s most graphic depictions of racial

violence, and one of the starkest confrontations of the theme at this

time.

“This really is

an extraordinary encapsulation of the devastating effects of racial

terror and violence on Black families in a way that really had not

happened in American art up to that point,” said Saywell.

Education

is another theme explored in “Witnessing Humanity.” Wilson often spoke

about how impactful his experience reading with his father was and how

it inspired a lifelong love of education and reading in him.

A

small version of “Father and Child Reading,” a bronze sculpture that

locals will recognize from Roxbury Community College, is displayed

inside a bright yellow interactive reading room. Here parents and

children, or any guest, can sit on comfortable chairs and read the

youth-oriented books Wilson illustrated, including one about Malcolm X,

or similar titles selected in partnership with the Boston Public Library

and provided by Frugal Bookstore in Nubian Square.

“Witnessing

Humanity” is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts from Feb. 8 through

June 22. Then it will travel to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New

York.

The curators

worked extensively with Martha Richardson, Wilson’s longtime gallerist

and friend who manages his artistic estate with his family. Richardson

has been cultivating Wilson’s archive since the artist passed away in

2015. On Feb. 15, “John Wilson: Self Portraits and Spot Drawings,” opens

at the Martha Richardson gallery, on Newbury Street, to complement the

MFA exhibition.

The

Museum of Fine Arts has historically struggled to walk the line between

its reputation as a globally recognized art museum and its identity as a

museum in and for the city of Boston. This exhibition is an example of

how those identities can coexist.

“His skill from the get-go is remarkable.

He was unflinching and had an unbelievably clear vision,” said Saywell. “And he’s been here in Roxbury all along.”

ON THE WEB mfa.org/exhibition/witnessinghumanity-the-art-of-john-wilson