There was a time in this town when Second Street was today’s Koke Mill Road, at the western edge of the city. Back then the Industrial Age, nurtured for decades on the east coast, was sweeping west like wildfire, riding steel rails and embracing Illinois’ new capital city, the third town to hold the honor.

Springfield was the lucky benefactor not only of the age, but of the man who helped shape the city’s promising destiny: Abraham Lincoln. As part of a merry band of Illinois legislators known as the “Long Nine,” he successfully engineered the relocation of the capital from Vandalia to Springfield to the domed building on the square which was soon out grown by bureaucracy in bloom. Its incapacity led to the 1868 groundbreaking for the awesome assemblage of stone and steel that serves today as the Illinois Statehouse.

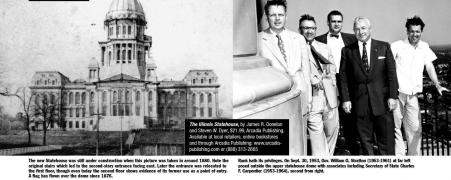

Springfield authors Jim Donelan and Steve Dyer have teamed with Arcadia Publishing to produce an informative pictoral book about the building which took 20 years to complete.

The timing of the book’s June 8 release, with a former state senator moved on to world prominence as chief resident of The White House, could not have been better.

It’s hard to imagine driving west on Capitol Avenue and looking through tall timber to gaze upon the Mather family mansion which once occupied what became the Capitol Complex.

The March 1865 photo of the house presented on page 9 reveals a home equal in grandeur to the contemporary Maisenbacher home over on Seventh, but the Mather mansion was destined to be razed to make way for the Lincoln tomb following the Great Emancipator’s assassination. When the tomb was built at Oak Ridge cemetery north of the city at the insistence of the widowed Mary Todd Lincoln, the site was selected for the new Capitol Building.

The book’s eight chapters present chronological views of construction, the new building from the ground to the top of the dome, including many of the Governor’s Offices through the years, the exterior of the building and grounds and views from Capitol Avenue.

Construction photos reveal 19th century life rarely encountered in other publications. Railroad tracks were used to bring building materials to the site. The clutter of piled stone, mounds of earth and detritus of progress dominated the scene for years.

Private homes remained on the grounds closeby during construction, and life went on. Perhaps inspired by the stretches of steps leading to the main entrance of the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington, D.C., an expansive stone staircase originally led to an entrance to the Statehouse at the second floor.

See also

|