Jackie Jackson caps her literary career with publication of The Round Barn, Vol. 4

Saying Jackie Jackson’s magnum opus is about a barn, is like saying Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is a history of rabbit holes. The Round Barn encompasses

a way of life that has all but disappeared. It captures the history of

an extraordinary family whose members will live forever, thanks to a

girl who kept notebooks beginning in second grade, and kept a promise to

her grandfather that someday she would write a history of his farm.

Jacqueline

Dougan Jackson’s notes, her extraordinary memory and her gift for

telling stories, paint a vivid narrative of agrarian life in the first

three-quarters of the 20th century. Her writing is colorful, intricate,

funny, heartbreaking and informative. Not only did she keep notebooks,

she also

collected a plethora of family photographs that illustrate the richness

of life on a working dairy farm in Wisconsin beginning in 1900.

At

times Jackie worried that the story of the farm would never be written.

She made many attempts to start but it wasn’t until 1976, when teaching

a writing class at Sangamon State University in Springfield, that her

inspiration came. She told her students, “Don’t write a line. Write a

page.” That year she took a sabbatical, went back to Beloit, set up a

card table in her old bedroom and began to write. Over the years she had

the first two books, Stories from the Round Barn, and More Stories from the Round Barn. After those two, she then went on to write the four volumes of The Round Barn: A Biography of an American Farm. Vol. 4 was published this week.

The

story began nearly 80 years before it would be put to paper. Jackie’s

father, Ronald, born in 1902, was the son of Wesson Joseph and Eunice

Dougan. Ronald would spend the rest of his life devoted to working with

his father, founder of the Dougan Dairy. Grampa is perhaps the central

character in Jackie’s book. The enterprise he and his family worked so

hard to make successful would grow to be considered one of the premier

dairy farms in the country. Later years saw Jackie’s dad expand the

business into one that included a hybrid seed company and later one of

the first to experiment in breeding cows using artificial insemination.

If she cared to, Jackie

could romantically trace her beginnings Paris, France. It was there,

while working as American Methodist volunteers to work with children who

had lost parents in World War I, that her mother and father met. Jackie

entered the world in May of 1928, and spent her childhood in what many

of us would describe as bucolic setting. The myriad stories that

comprise the Round Barn books are more realistic. Many at the farm were

hit by the Spanish Flu pandemic. The year after Jackie’s birth, the

Great Depression descended; farmers were hard hit. Vaccines for people

and animals had not yet been discovered. Bad weather and poor crops were

all part of the hardships of farm life. Bankruptcy papers were drawn up

in 1930, but never filed. Also part of farm life, however, were good neighbors and an abiding faith in God.

Grampa

had always felt he was called to be a minster. He was raised in the

Methodist faith, and had a lifelong aversion to smoking and drinking,

both of which he considered serious sins. But at an early age, he began

to lose his hearing. It soon became clear that a deaf preacher would

face insurmountable barriers. So he turned to his other strong suit --

farming. Jackie insists that The Round Barn is not her memoir,

that it is a memoir of the farm. Within that framework W.J., Jackie’s

grandfather, looms as the central character of the book. Like the barn,

he stands at the center. Life on the farm radiates from him. He was

clear on what he felt his family’s life there should encompass, and on

the silo of the barn, he painted his “aims for the farm” for all to see:

1. Good Crops

2. Proper Storage

3. Profitable Live Stock

4. A Stable Market

5. Life as Well as a Living

In a series of articles for the magazine Hoard’s Dairyman, Grampa

expounded on the last aim. He urged people to “enjoy the simple

pleasures – the sweep of the landscape, the open sky, the forest and the

field and stream, as well as all animate life. … In

the home we have an abundance of light, some inexpensive art, music and

literature, and withal, a home spirit.” He must have taken his aims to

heart, because in 1925 he was named a “Master Farmer,” one of 23 Midwest

farmers so honored.

When

he died in 1949 Jackie felt remorse that she had not yet kept her

promise to write a book about the farm. Life had intervened. After

graduating from Beloit College in 1950, Jackie married, and she and her

husband move to Ann Arbor to receive graduate degrees from the

University of Michigan, she in Latin and he in English. They live on the

outskirts of town in what she describes as “shanties,” and what others

called graduate student housing. She’s taking a full course load and

playing cello in the university orchestra. She realizes she is homesick.

The end of the semester approaches and she comes to terms with how her

life has changed. She describes how she feels in this beautiful passage:

There

has been another clock within her. She didn’t set it nor place it

there. It’s been geared not to hours but to cycles; the daily precession

of milking and bottling, feeding and cleaning, the yearly procession of

planting, cultivating, harvesting. It’s been set to sun, moon, heat,

cold, wed, dry. But now if there’s a heavy spring freeze, she puts on a

coat without sensing the loss of crisp that might result from too-late

planting. If the sky lowers black, she takes an umbrella without feeling

the sway of the hay wagon racing to reach the barn before the

cloudburst. Her dailiness is now this class, that lecture, the next trip

to the stacks. This was true before, too, but the steady

throb of the milking machine was the heartbeat of the dailiness, the

Greenwich underneath that all the other clocks were timed to. It was the

ground she’d stood on, the air she’d breathed. She has no special

moment, no epiphany to explain the realization of loss that comes over

her. She only knows that something elemental is gone and has been gone

for some time. That it’s probably irretrievable, unless she changes the

path she’s treading.

It

would take almost 20 more years, four children, and a divorce before

that “something elemental” would return to her. It came as a result of

her father’s illness and a longremembered promise to Grampa.

In

1967 Jackie’s dad, Ronald, fell ill and was in the hospital for several

weeks. She traveled to Beloit many time to sit by his bedside and take

what some would call an oral history, asking him to tell her stories

about the farm and family. One of those stories was one of the earliest

Jackie had written as a child and would find decades later in an old

brown notebook. It is a tale about a girl and her blue-ribbon calf at

the local 4-H fair. While the girl in the story is a top prize winner,

Jackie’s real-life fate was not so glorious. She and her brother, Craig,

both entered calves in the fair. Craig’s calf behaved, but Jackie’s

bolted and she found herself face down in the show ring with the calf

having headed for the barn. The story of the successful girl, Jackie

said, was a way of “licking her wounds.”

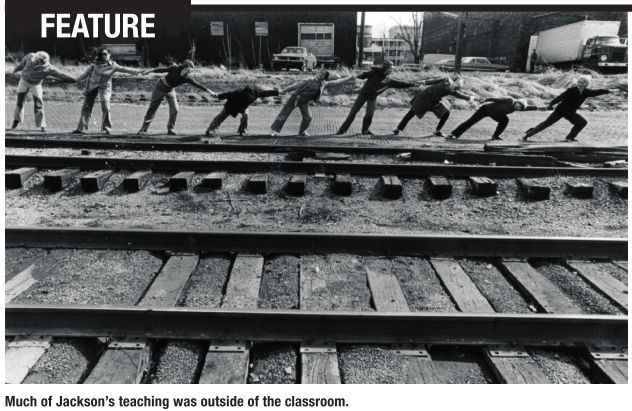

Beginning in 1950 Jackie saw her life turn from farm girl to scholar

to wife and mother. In 1970 she began one of the most important turnings

in her life. She moved with her four daughters, Damaris, Megan, Elspeth

and Gillian, to Springfield, Illinois, to be part of an educational

experiment on the prairie called Sangamon State University. W.J. had

described an educated person, as a person who has taught “her mind to

think, her hand to act, and her heart to feel.” With these arrows in her

quiver, Jackie would begin to teach others how to embrace these goals.

Jackie found her true

calling in teaching when she became a part of SSU. It was the perfect

proving ground. Established as a two-year university for juniors and

seniors, the school had an open admissions policy and, for the first two

years, no grades. This liberal learning philosophy encouraged

independent study programs. The plan called for recruiting the finest

and most innovative teachers to begin what was, in fact, an experimental

idea. The initial faculty comprised 45 pioneering professors. Many of

them are still among Jackie’s closest friends. Over the course of her

career one of the course of her career

one of her greatest pleasures was co-teaching with her colleagues. The

focus was to be on establishing a public affairs university with

corresponding colloquia sessions on local, national and international

affairs. Its other emphasis was to graduate superior elementary and

secondary teachers.

Jackie’s

degree from the University of Wisconsin was in Latin. At SSU she taught

courses in English literature, perceptual writing, and a history of

children’s literature (everyone who took this class left having written

their own children’s book). When it comes to children’s literature,

Jackie had the credentials. Starting in the early 1960s, Little

Brown and Company has published several of her children’s books (see p.

15). She also taught in the genres of fantasy and mystery, and the

aspects of women’s liberation.

Because

SSU was a junior and senior university and because it offered so many

night classes, most students at the beginning were adults. Jackie

recalls a writing class she taught at night. She imagined her students

having worked all day, making evening arrangements for their families at

home while grabbing a quick bite for themselves, then rushing to be at

class on time. Knowing that such a frazzled pace would not encourage

creativity, the first thing she did after all her students were at their

desks was to turn out the lights. And then she played Mendelssohn’s

Rondo Capriccioso Opus 14. At the end of the

piece, students were relaxed ready to write. Jackie herself grew up in a

musical family. She played the violin, but when both of her sisters

played that same instrument, they encouraged her to learn the cello. She

went on to play in more than one symphony orchestra.

Jackie

Jackson could not be described as shy. She may have met a few strangers

but they weren’t strangers for long. When she meets someone, she is

engaged in that person’s interests and eager to share her own. Her

outgoing personality often turned into opportunities for her students.

Jackie planned summer field trips to England and Scotland. One of the

books she had taught in her fantasy class was Richard Adams’ famous Watership Down. She

remembers biking in the country to find Mr. Adams’ house. He opened the

door upon her knock. She introduced herself and asked if her students

might come back to see the setting of his book. He invited her in for

tea, and later her students were privy to a private tour of the down,

led by Adams himself. She also arranged a visit with C. S. Lewis’

stepson, and a trip to the Black Museum at Scotland Yard, and an Oxford

pub visit with Colin Dexter for her students studying mystery writing.

For 20 years, beginning in

1975, Jackie produced a radio show on WSSR, later WUIS. “Reading,

Writing and Radio” was an outreach program to elementary school children

across central Illinois. Students in 90 classrooms were given radios to

listen to the program. SSU faculty and experts from many fields were

recruited for programs on a variety of topics. Pen pals were established

across communities. Every class visited the radio station. And in the

spring, they attended a Jamboree. Jackie remembers it as “the liveliest

day on campus,” and suspects that many of the children later attended

SSU.

One of Jackie’s books, The Endless Pavement, was

the first dramatic performance at the Sangamon Auditorium Theater.

Bemoaning the fact that the automobile seemed to have taken over our

lives, Jackie envisioned a world where people were ruled by their cars

and only dreamed of using their legs to get somewhere. She fondly

remembers dozens of children in toy cars zooming around the stage.

After

she retired from teaching, Jackie has concentrated on what she loves –

writing and her family. She has six grandchildren and two

great-grandchildren. In her big house on Fifth Street (rumored to have

been visited by Abraham Lincoln) Jackie has hosted a writers group for

years. Many members of the group have gone on to have their work

published. She has been the Illinois Times poet for more than 12

years. When John Knoepfle gave up that post, then editor Roland Klose

approached Jackie. “I’m not a poet,” she told him, to which he replied,

“But I want you and I know you can do it.” The poems are enriched by the

rich life Jacqueline Jackson has lived. She has shared this wellspring

in a series of “Liberty” chapbooks.

Agingpoem #1

when tradepeople waiters ushers and such start calling you “young lady Then you know you’re getting old

Jackie

Jackson is 89 years old. When I expressed my disbelief of this fact,

she joked that on a recent trip to London, her older sister Pat, 92,

chided her for not keeping up with group.

Corrine

Frisch is a freelance writer. She has known Jackie Jackson for more

than 20 years. She first met Jackie at Lincoln Library, Springfield’s

public library, when she was working as its PR director and Jackie was

presenting a children’s program.

Julie’s Secret Sloth – 1953. Julie hides a pet sloth in the house, right under the noses of her parents. Little Brown and Co. The Taste of Spruce Gum – 1966. Libby learns to appreciate the different qualities of life in New England. Little Brown and Co. Missing Melinda –

1967. Sisters Cordelia and Ophelia move to their uncle’s house, and

discover Melinda, a valuable antique doll. When the doll disappears, a

mysteryadventure ensues. Little Brown and Co.

Chicken Ten Thousand –

1968. Chicken 10,000 was just like chicken 9,999 until she escaped the

egg factory’s incubator and discovers what the life of a hen should be. The Paleface Redskins –

1968. Children on vacation in Wisconsin are upset when a Boy Scout camp

moves in, disturbing their idyllic summer. Little Brown and Co. The Ghost Boat –

1969. Five children are convinced that the rowboat they see moving

across the lake is propelled by the ghost of a dead fisherman. Little

Brown and Co. Spring Song – 1969. An ode to spring based on a traditional poem. Kent State University Press The Orchestra Mice –

1970. Clarissa longs for a musical life. She marries Sam Mouse and

together they teach their little mice to appreciate classical music.

Contemporary Press The Endless Pavement – 1973. Living in a time

when people are the servants of automobiles and ruled by the master auto

of the planet, Josette longs to leave her rollabout and try her legs.

Seabury Press Turn Not Pale, Beloved Snail: A Book about Writing Among Other Things –

1974. Using excerpts from her own writing and that of her children and

other authors, Jackson suggests a variety of approaches to learning to

write.

These books are currently out of print but are readily available from booksellers online.

Book Coming Out Party

Jackie

Jackson will host a Coming Out Party for the last volume of Round Barn

on Wednesday, Nov. 9, from 5 p.m. till 7 p.m. at First Presbyterian

Church, Seventh and Capitol Streets, in the Cook’s Lounge. Copies of the

Round Barn book will be for sale at a discounted rate. Other writers

will have their books available for sale. Volume 4 of “The Round Barn

Book” will also be available at Prairie Archives downtown, at Barnes and

Noble, and from Jackie herself. For more on the book, or to order, go

to roundbarnstories.com.