Yeah, Roy so cool, That racing fool, he don’t know what fear’s about.

He do 130 mile an hour, smiling at the camera With a toothpick in his mouth.

– Jim Croce

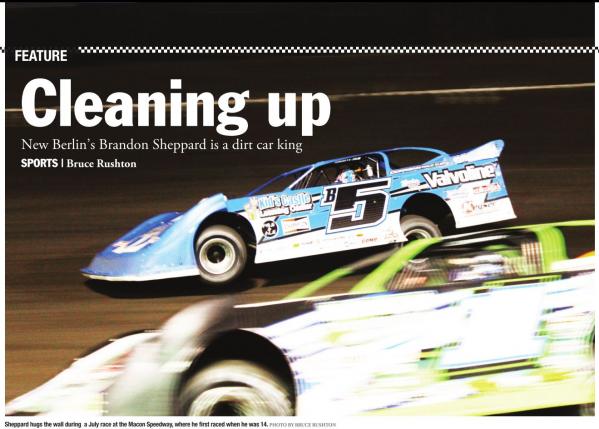

Before the evening’s first green flag at Macon Speedway near Decatur, Brandon Sheppard wipes down his race car.

The vehicle looks more a cross between a Civil War ironclad and Star Wars fighter than a car. It is, in the world of racing, a stock car, at least technically, but looks nothing like a Ford or Chevy save for its size, which is that of a full-fledged sedan. There is no windshield and just one seat. The cockpit resembles a manhole cut from surrounding metal, just enough room for the driver’s head to poke through. Nothing much more, really, than a roll cage, wheels, 800-plus horsepower motor and suspension made for banked dirt courses, some smaller than a high school running track, populated by two dozen or so racers traveling freeway speed or better.

The sheet metal body provides plenty of space for sponsor stickers but otherwise seems superfluous. In an hour, it

will be spattered with dirt. By night’s end, it will be torn and

scarred, large sections rubbed clear through to gleaming aluminum, a

byproduct of going fender-to-fender in two-wide turns where the curious

physics of racing on dirt require drivers to turn right to go left,

three wheels touching earth in controlled slides that leave the left

front tire spinning lazily in the air until halfway down laughingly

short straightaways – pauses in turns, really – on this track 45 miles

east of Springfield that measures one-fifth of a mile.

“You

can go to any other track in the country and you can fit this inside

it,” observes Sheppard, who first raced this oval a decade ago, when he

was 14.

If you can

race here, they say, you can hold your own anywhere. Once racing begins,

dirt will fly everywhere, including the grandstand, where it gets deep

into hair and inside clothing and makes it impossible to drink from

cups. The near-white cement wall surrounding the track is quickly caked

to the point that crews scrape away dark-chocolate loam between races so

that drivers can discern the difference between soft dirt and disaster.

If you’re doing it right, you’re coming within inches of that wall,

according to proponents of the high side, Sheppard being one. They call

it the cushion, the place where dirt piles up after being thrown outward

by cars sliding in

the middle and near the infield. Going high on the track, fans and

drivers say, is the best way to keep momentum and gain traction, never

mind that the low side offers a shorter trip to the finish line.

Given

all this dirt, why does Sheppard wipe down his car, which already looks

plenty clean, before heading to the track in hopes of winning tonight’s

$12,000 purse? It doesn’t appear to be nervous energy – he’s already

yawned his way through a driver’s meeting. Perhaps the aerosol spray

with a sickly sweet petroleum odor that he’s rubbing in with a rag makes

the car a bit slicker and so helps shed dirt – after all, the less

weight the better. Or maybe it’s a love for machinery that he has

learned to master.

There’s

also family to consider. Sheppard is a fourth-generation race car

driver, and smart money says that his three-year-old son Jase, who rides

double as his father putts around the pits on a small motorcycle, will

follow in his tracks. Most of Sheppard’s races are run in a teamowned

car, but his ride tonight is owned by his grandfather. He grew up

watching his father and grandfather race dirt track, but never with as

much success as he’s enjoyed.

“Honestly,

I don’t get to race around my family a lot,” Sheppard says. “I wouldn’t

do it if I wasn’t trying to make them proud. I don’t do it for me.”

“He’s becoming a superstar”

At 24, Sheppard is becoming the king of late-model dirt car racing,

with “late model” signifying the latest in design and technology.

Through

the end of July, the New Berlin native has notched 22 victories,

including a streak of five in a row that lasted from June 30 through

July 4. He races as many as five days a week and sticks mostly to the

World of Outlaws circuit, a series of more than 50 races sponsored by

Craftsman Tools and held on tracks in 20 states, plus Canada. Fans pay

$30 for tickets and an equal amount for pit passes to witness what many

consider the top echelon of dirt car racing.

“It’s grueling,” Sheppard says. “It takes a lot out of a guy to drive all night to the next track.”

Sheppard

won’t get NASCAR rich – while he’s surpassed $200,000 in winnings so

far this year, purses are split with the team’s owner, who provides the

car, mechanics and transportation between races while hustling up

sufficient sponsors to make ends meet. Although his name is plastered on

t-shirts sold trackside, Sheppard’s face won’t cause many double takes

at Walmart. But it’s a living that comes with the privilege of not

needing a day job and being able to say that you are a professional race

car driver, even if you have to help change tires in the pits.

“If you’re looking at making a living as a race car driver, Brandon’s in a

pretty good position,” says Mark Richards, team owner. “He has a chance

to make some money here, some pretty good money, for the next how-many

years – he’s good for at least 20, I’m sure, if nothing happens to him

and he stays healthy and everything. There are guys out there doing this

who are in their 50s.”

Sheppard

has won before. Last October, he captured his second Dirt Track World

Championship race in Ohio, nabbing a $100,000 purse for his biggest win

ever, uncharacteristically sticking to the track’s low side while the

runner-up ran high during a race that didn’t prove close. He also won

the championship in 2012. But he’s never taken so many checkered flags

in a year as he has this season, which started in February and will wind

up in November.

“This

is the season he’s becoming a superstar,” says Kevin Kovac, a senior

writer with dirtondirt. com, a website devoted to dirt track racing.

Even when he doesn’t win, Sheppard excites.

After winning a consolation race in Nebraska last month, he had a choice: Take home a $3,000 prize or start in

the back row of the main event, which paid $53,000 to the winner. For

Sheppard and his team, it was an easy call.

“That

(the consolation prize) is not an option for this team – we’re here to

win the race, so if we’ve got a chance to race, we’re going to race,”

says Richards. “There’s a lot of things involved. There’s sponsors

involved, and we’re here to represent them. The $3,000 is fine, but

we’re looking at $53,000.”

Starting

in 32 nd place, Sheppard picked his way through the field and ended up

taking second place. “He got up to fifth, and you could tell: He was

going to do what he’s got to do,” recalls Kovac. Richards said he

believes that Sheppard would have won if not for a caution flag with 11

laps to go. After the caution, the winner, Richards says, started taking

the same line around the track as Sheppard, who lost by less than a

second, according to the write-up on dirtondirt.com, which called

Sheppard’s effort a “fairy tale run.”

“The

kid’s got big balls, man,” winner Tim McCreadie told the website after

taking the checkered flag. “He came from dead last and

gave it a shot.”

There

is plenty of pressure. Racing is a business for Richards, who owns

Rocket Chassis, a West Virginia company that manufactures chassis for

race cars.

“If this

car wins, we sell race cars at Rocket Chassis,” Richards says. This is

also our researchand-development team – we research and test any new

parts with this team. We also gather information that we pass on to our

customers. We need it to make sense, too – it has to make financial

sense. We need to win races.”

For

all the technology, dirt track remains very much a human endeavor.

Speed records at many dirt tracks have lasted for decades. “Tires and

shocks and motors are better today, but yet, a lot of the old track

records still stand,” says Terry Young, general manager of Hoosier Tire

Midwest, a racing tire supplier, and a member of the Springfield

Metropolitan Exposition and Auditorium Authority board. “You reach a

point where you just can’t get any faster.”

Confident, not cocky Dirt car racing is not without risk. Two late-model drivers

died after crashes last year, one shortly after a horrific fire on the

track. And so some degree of nerve, confidence, courage – call it what

you will – is necessary to succeed, or even try.

“I

don’t think it’s nerve as much as it is confidence,” Richards says. “If

nerves are bothering you doing this, you shouldn’t do it. When you

climb in, you look at the risk you’re taking, or you should.”

Kovac says that you can just tell with some drivers.

“They

can step on the gas and they’re not afraid,” he says. “Brandon’s only

24, but he’s going to be good for a long time. … He’s confident, but

he’s not cocky.”

Before

and after races, Sheppard appears unflappable. Asked to deconstruct a

victory, he will typically break down the race into segments – first

this happened, then that happened – talk about tires and other equipment

for a bit, praise his crew, thank his sponsors, then head back to the

pits with all the emotion of a fellow who has just been asked to

describe his day as a certified public accountant. The lack of emotion

can drive his father Steve nuts.

In

February, Sheppard eked out a thriller in Florida, going from third

place with two laps remaining in a 50-lap event to win by a half-car,

coming around the outside to pull ahead on the final turn while the

crowd roared and the announcer screamed his name.

“We

just had a little luck on our side and we were fortunate to have a good

race car and we’re thankful,” he said, almost flatly, during a

post-race interview conducted with the barest of smiles.

“I’m

like, ‘Man, what is wrong with you?’” Steve Sheppard recalls of his

son’s post-race demeanor. “You just pulled off the move of the year.

That’s going to be considered the race of the year. That was the move of a lifetime. There was no emotion. I asked him, ‘Why weren’t you excited?’ He said ‘I was excited.’ I said, ‘You couldn’t tell.’”

Richards says the younger

Sheppard is the most humble driver he’s seen in victory lane. “A lot of

young guys in this business, they get overwhelmed with the notoriety, or

the perception of them being a winner, and they forget about, hey,

tomorrow’s another day, and we’ve got to go do it again,” the team owner

says. “That race is behind you. Do the pictures, get it over with and

we need to worry about the next one.”

It’s

the sort of focus that Steven Sheppard, Sr., Brandon’s grandfather,

encouraged years ago, when the boy, not yet in high school, was tempted

to play football. His grandfather told him that he was willing to foot

the bill for a very expensive pastime, but the boy had to choose between

football and the track.

“I

hated to do that to him, but if you want to be good at something,

you’ve got to do that – you can’t do everything, you know what I mean,”

the grandfather says. “I said, ‘If we’re going to do this, and you’re

going to do this, and you want me to spend the money, the only thing I

can tell you is we have to do it right and it can’t be a fly-by-night

thing.”

A humbling sport Steve Sheppard, Jr.’s racing career overlapped a bit

with his son’s. “When he started beating me, that’s when I decided to

hang it up,” the father says. Like his son, the elder Sheppard favored

the high side, where cars slide close to the wall. “Racing’s very

physical – when you run the high side, it’s demanding,” Steve Sheppard

says. “You’ve got to be so precise to run the high side.”

Aside

from preferring to race near the wall, the son drives nothing like the

father did. Steve Sheppard had a reputation for full-on, aggressive

driving. He is legendary for once stomping the hood of a car that pushed

him into the wall of a straightaway, knocking him out of the race.

The hood gave way like only

a piece of sheet metal can when jumped on by a full-grown man. After

destroying the hood, he went for the driver, who remained in the cockpit

as race officials tackled Sheppard and took him to the ground. He

cannot imagine such an outburst from his son, whom he says has had just

one speeding ticket since turning 16.

“He

don’t have the temperament for that,” the elder Sheppard says. “I’m

very hot-headed, and I think he learned from me not to be. … He’s a very

respectful driver. He won’t go and slam into the side of someone to get

to a certain position. I wouldn’t be afraid of doing that at all, if

that’s what I needed to do.”

Richards

first saw Brandon Sheppard race at a track in Lincoln when he was 13 or

14. “You could just tell he had it,” Richards said. “I said ‘Who’s that

in the five car?’ That’s when I started watching him.”

Sheppard

says that he hasn’t always been comfortable in a race car. “At the

beginning of my career, I was always really nervous,” he says. “I tried

to stay out of people’s way and earn respect.” Even now, he’s known as a

finesse driver who doesn’t force things. “You’ve got to be patient for

100 laps,” he says.

“Patience

is what he has, and a lot of drivers don’t,” the elder Sheppard says.

“I ask him, ‘Why don’t you drive harder?’ He says, ‘Dad, if the car’s

fast enough, be patient, and it will come to you.’” Smooth – that’s what

they call Sheppard’s style of racing, the sort of driving that’s easy

on tires so they’ll grip when you need them in the late going. “He runs

hard, but he doesn’t burn his stuff up,” Young says.

A July 26 race at the Fayette County fairgrounds in Brownstown, about 80 miles southeast of Springfield, was classic Sheppard.

He took the lead on the

first lap of the 40-lap contest, staying high, keeping his speed

consistent and gaining as much as a straightaway on his closest

competitor. But a yellow caution flag – they can be frequent as cars

spin out or break down – with four laps to go proved an equalizer as the

field bunched up for the restart.

While

Sheppard remained high on the track, Chris Madden, a driver from South

Carolina, found traction near the infield and nearly pulled even in a

battle for first. On the final turn, a sliding Sheppard kisses the wall

with his right rear quarter panel – surely Madden would best him now.

But it was an “excuse me” touch, just enough to cause a slight fishtail

but not hard enough to break momentum. Sheppard’s official margin of

victory was less than four-tenths of a second.

Afterward,

he talked about tires – no one, he says, seemed to have the right tires

installed. His brush with the wall goes unmentioned. One night earlier

in Macon, he talked about the realities of racing as he sat in the pits,

waiting for the evening’s first heat. Sure, he’d won a lot of races, he

acknowledged. But anything, he notes, can happen on the track.

“It’s

really a humbling sport,” he says. He runs near the front for the first

half of the 100-lap main event, but is forced out on the 77 th lap due

to a busted shock. Humble or no, frustration is evident in Sheppard’s

eyes as he climbs from his car, studies the rear suspension, then turns

to the track, watching stoically from the infield as cars roar past.

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].