Smart on crime

Put fewer in prison to save money. Get more in rehab to save lives.

PRISONS | Patrick Yeagle

Each year, Illinois spends about $1.3 billion to lock up more than 48,000 prisoners. Nearly half of those who are released return to prison within three years. Parolees in Illinois face significant barriers to getting jobs, finding housing and even obtaining health care, which vastly increases their likelihood of committing new crimes. By all accounts, Illinois’ correctional system does a poor job of correcting anything, and it has been that way for decades.

The good news is that Illinois lawmakers are considering changes to the system which are intended to reduce the number of people who go to prison and the number of people who return there. Experts say that by being smart on crime instead of merely tough, Illinois can improve public safety, foster equality and create a system that actually reforms criminals instead of warehousing them.

That reform could include reducing prison sentences for minor crimes, sending certain criminals to treatment instead of prison and changing the parole system so parolees aren’t sent back to prison for minor violations.

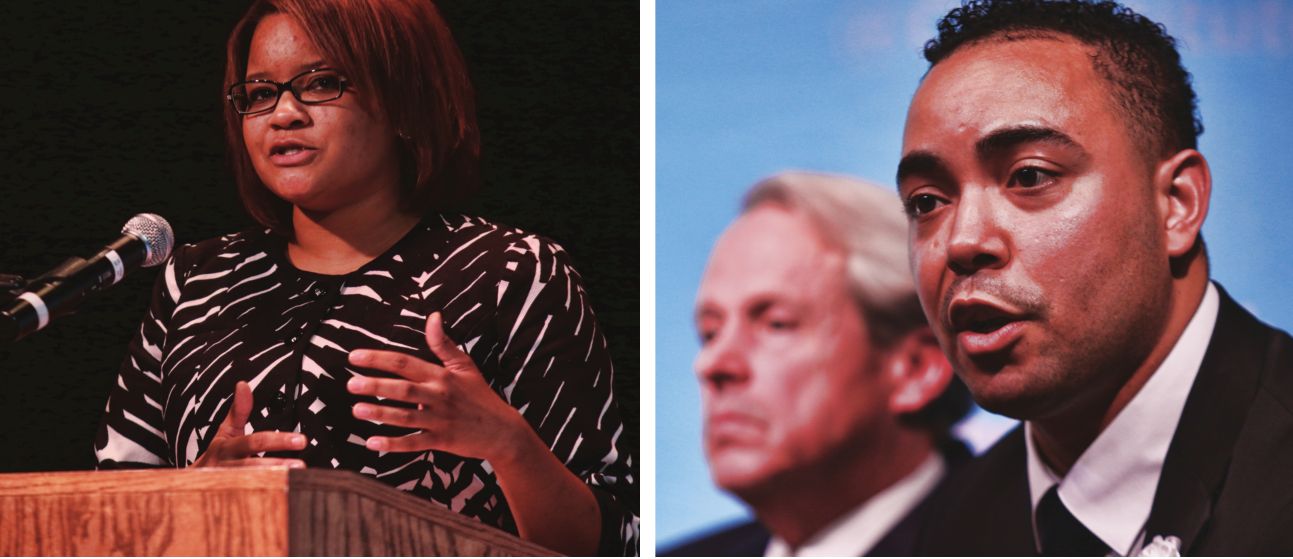

Samantha Gaddy, public safety policy adviser to Gov. Bruce Rauner, says Rauner visited Logan Correctional Center in Lincoln, about 30 minutes north of Springfield, earlier this year.

“The governor was appalled by what he saw at Logan,” Gaddy said during a May 20 panel discussion in Springfield on criminal justice reform. “He wanted reform – quickly.”

The John Howard Association, a prison reform advocacy group, released a report on Logan Correctional Center in December 2014, calling the prison “overcrowded, underresourced, and ill-conceived.” In 2013, former Gov. Pat Quinn attempted to save money by consolidating most of the state’s female prison population into the male medium-security prison at Lincoln, but the move instead created a host of other problems, including extreme overcrowding, failure to meet the needs of female prisoners, lawsuits over mental health treatment and even a spate of suicides at the prison.

In February, the newly inaugurated Rauner issued an executive order creating the Illinois State Commission on Criminal Justice and Sentencing Reform, a bipartisan panel of lawmakers and experts tasked with reducing Illinois’ prison population 25 percent by 2025 without negatively affecting public safety. While this isn’t the first time a high-level state commission has studied potential criminal justice reforms, observers note that there is unprecedented agreement between conservatives and liberals in the Illinois Statehouse on the need for reform. Additionally, Illinois’ perennial budget crisis has both Republicans and Democrats looking to the prison system for cost savings. It appears the time is ripe for change.

The problem During the 1980s and 1990s, Congress and state legislatures across the U.S. passed “tough on crime” laws meant to act as a deterrent against crime. Such laws included increased penalties for even minor crimes, mandatory minimum prison sentences and “three strikes” laws that imprisoned people for life after three convictions, sometimes for minor crimes.

As a result, the prison population in the U.S. now dwarfs that of any other nation. While the U.S. has about 5 percent of the world’s population, nearly 25 percent of all prisoners in the world are incarcerated here. More than 2.2 million people are behind bars in the U.S.

Illinois is a microcosm of this national problem. The state has 29 adult prisons, which were originally built to hold about 32,000 people but currently hold nearly 48,000. The prison population in Illinois has increased 350 percent since the 1980s, and the Illinois Department of Corrections expects that number to continue climbing. In 2014, Illinois spent $22,655 on average per prisoner, and incarceration consumes almost 4 percent of the state budget. [See “Illinois prisons: Standing room only,” March 4, 2010, at illinoistimes.com.]

There are so many prisoners and ex-prisoners in Illinois that the state

has trouble finding places for them to live when released. Most inmates

in Illinois must serve a parole period known as “mandatory supervised

release” after their prison sentence, which requires that the parolee

have a place to live. If the person can’t arrange their own

accommodations or stay with family, the inmate ends up serving out his

or her parole in prison.

Experts

warn that overcrowded prisons are unsafe for both prisoners and guards,

and the U.S. Supreme Court even ruled that California’s prison

overcrowding was unconstitutional, sending a warning to other states

with the same problem.

David

Camic, a veteran defense attorney and senior fellow at the

right-leaning research group Illinois Policy Institute, says one of the

main problems in Illinois is mandatory minimum sentences, in which a

judge must impose a prison sentence for a given offense, regardless of

the facts of a case.

“There are traffic offenses where you must go to jail,” Camic said. “It’s absurd.”

Camic

has represented clients who faced prison sentences for crimes as minor

as stealing an iPhone. Judges often tell Camic that they would like to

impose a lesser sentence based on the facts of a case, but the law won’t

allow them to.

“There

are certain people who everybody agrees ought to go to prison – for

example, if you commit murder or hurt somebody intentionally,” Camic

said. “But when you allow your knees to jerk, and let that reaction

control what you do, you miss a more reasoned, effective solution. There

has to be some realization that we can go too far.”

Todd

Belcore is the community justice lead attorney for the Sargent Shriver

National Center on Poverty Law, based in Chicago. Belcore acknowledges

there is some deterrent value in prison sentences, but he says 40 years

of mandatory minimum sentencing have revealed the limit of deterrence.

“A

grandma carrying a gun for safety in a dangerous neighborhood is

treated the same as a gangbanger in court,” he said. “Mandatory minimums

create victims of the law rather than protecting people. Opposing it

doesn’t mean you don’t want people punished, but that you want the judge

to have access to information and craft a sentence fitting the crime.”

Belcore

says another issue contributing to Illinois’ large prison population is

parolees being sent back to prison for technical parole violations that don’t constitute actual crimes.

According

to data from the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority,

between 1990 and 2013, Illinois sent 137,514 people back to prison for

technical parole violations. In the early 90s, the number of people sent

back to prison on technical violations each year never broke 3,000, but

in 2001 and in every year since, that number has hovered between 7,000

and 11,000 people each year. Parolees can be deemed in violation for

something as simple as being late to report to a parole officer or being

around someone else with a criminal conviction.

“In

certain communities, just going to church or the grocery store means

you’ll inevitably have contact with someone else who has a conviction,”

Belcore said. “We need to allow more grace in the process.”

Because

Illinois is so quick to hand out prison time for even minor offenses,

Belcore sees the state’s massive corrections spending as “a blank check

for an ineffective system.”

“It’s

not just ineffective,” he adds. “It devastates individuals. It cripples

families. It strips people of the opportunity to access the American

dream.”

Belcore is

also troubled by the disproportionate percentage of people of color

behind bars in Illinois, especially for drug-related offenses. Despite

being 15 percent of the Illinois population, African-Americans make up

57 percent of the state’s prison population. Although research from the

Centers for Disease Control shows that white people and black people use

drugs at similar rates, data from the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics

show black people are more likely to be convicted for drug offenses and

be sentenced to prison. In Illinois, the arrest rate between 2001 and

2010 for marijuana possession grew 14 percent for whites but 51 percent

for African-Americans. Statewide traffic stop data also show that black

people are more likely to be pulled over while driving and searched for

drugs.

Belcore says

when Cook County Board president Toni Preckwinkle hosted a delegation of

emissaries from Africa, she took them on a tour of the Cook County

jail. According to Belcore, the emissaries said “We’ve seen the jail for

black people; now where is the jail for others?” Former Illinois

appellate justice Gino DiVito says Illinois must deal with the effects

of addiction and mental illness as part of the reform push. DiVito, a

noted author and expert on criminal justice in Illinois, says addiction

and mental illness are the root causes of a significant amount of crime.

Drug courts aimed at helping addicts have been established in many

courts across Illinois, and mental health courts are also beginning to

spring up, but both are greatly underfunded and limited in scope. [See

“No room at the inn: Alonso Travis died waiting for help,” Jan. 24,

2013, and “Treatment instead of jail: Courts try new approach to mental

illness,” April 23, 2015, at illinoistimes.com.] “What can I as a judge

do with this person who may be selling small quantities of drugs but is

also an addict?” DiVito said. “You know darn well if you release them on

their own recognizance, they’re going to be repeating the same

offenses. Right now, judges don’t have options. We have to address the

root cause.”

The

solutions Illinois has toyed with criminal justice reforms in the past,

and the ideas that were implemented seem to have made a difference. In

2009, Illinois created Adult Redeploy, a program aimed at diverting

certain offenders away from prison toward rehabilitation and treatment

services in their own communities. As of February 2015, the program had

saved the state $50 million by sending more than 2,000 nonviolent

offenders to treatment instead of prison.

The

Sentencing Policy and Advisory Council (SPAC) was created in 2009 to

study the effects of criminal justice policy in Illinois and recommend

changes. SPAC’s past analysis has revealed several trends in Illinois’

criminal justice system. One example is the increase in the catch-all

“unlawful use of a weapon” charge, which contributed to the state’s

increasing prison population but produced only “minimal effects” on

public safety. The UUW charge was created in 2000 to deal with

gang-related crimes, and the penalty for a UUW conviction was increased

repeatedly in the years that followed. SPAC’s research shows that while

recidivism rates for UUW offenders fell slightly between 2001 and 2008,

so did recidivism among other offenders, indicating that the increased

penalties for unlawful use of a weapon had little deterrent effect.

The

legislature has done little with SPAC’s findings so far, but the group

is now providing Rauner’s reform commission with data, expertise and a

slew of recommendations for decreasing the state’s prison population

without endangering the public.

Rauner’s

criminal justice reform commission has met three times since late March

and established subcommittees to discuss possible cost savings, how to

implement changes and other topics. The commission most recently met in

Springfield on June 3 to examine how to develop and fund stronger

rehabilitation services. The commission will send Rauner an interim

report on July 1 and issue a final report in December. That means

reforms which result from the commission’s work may start appearing in

bill form at the Statehouse during the 2016 spring legislative session,

although there’s nothing preventing lawmakers from voting on reforms

earlier than that.

Among

the reforms under consideration are reducing or eliminating mandatory

minimum sentences in criminal cases, expanding programs that divert

offenders to treatment instead of prison and reducing the number of

parolees sent back to prison for technical parole violations. The

commission may also consider reclassifying certain crimes to carry

shorter potential sentences, repealing laws that ban felons from holding

certain jobs or living in certain places, and releasing geriatric

prisoners who pose no public safety risk and whose health care needs

create an outsize financial burden.

Todd

Belcore, the attorney with the Shriver Center, says that felons in

Illinois are banned from holding a barber’s license – an example of the

numerous restrictions in Illinois that prevent people with criminal

convictions from reintegrating into society.

“It

destroys the heart and soul of people who are trying to stay on the

right track,” Belcore said. “These are people who have paid their debt

to society.”

The rub

Despite the promising outlook for criminal justice reform in Illinois,

there are some potential complications which could derail progress.

The

contentious budget showdown between the Republican governor and the

Democratcontrolled legislature has seen both sides seemingly relishing

the battle and spending political capital that may be needed in future

clashes. Rauner has already alienated some prounion Republicans, who

have in turn alienated the unions they support – the same unions which

may fight reform if it means prison closures and the loss of union jobs.

That’s to say nothing of the union anger Rauner himself has courted by

pushing for “right-to-work” zones and other anti-union measures.

Still,

the bipartisan nature of Rauner’s reform commission and the strong

appetite in the Statehouse for systemic changes may be enough to carry

the reforms. Members of the panel include Sen. Kwame Raoul, D-Chicago,

an attorney and leading civil liberties voice in the Illinois General

Assembly, Rep. Scott Drury, D-Highwood, a former Assistant U.S.

Attorney, and Rep. John Cabello, R-Machesney Park, a detective with the

Rockford Police Department and sponsor of a bill to reinstate Illinois’

death penalty.

Reform

advocates will likely have to convince state’s attorneys and certain

lawmakers with law-enforcement backgrounds who may see the changes as

destroying the deterrent effect of prison.

Former

representative Jim Sacia, a Republican from Pecatonica in northern

Illinois, spent 28 years as an FBI agent before being elected to the

Illinois House in 2003. Sacia calls himself a strong advocate for the

death penalty and was considered in the Statehouse to be one of the

toughest of the tough on criminal justice matters.

“The heinous things I saw gave me perspective on the criminal justice system,” Sacia said.

But even Sacia acknowledges that Illinois spends too much money locking too many people up for too long.

“Could we handle people in prison better?

No doubt,” he said. “I believe we overly encumber our correctional institutions, but that’s not to imply that I’m soft on crime.

Quite the contrary.”

Sacia’s

stance may be the key to passing reforms in Illinois, because it

redefines “tough on crime” to mean “smart on crime.” Todd Belcore

summarizes it this way: “Soft on crime means making easy decisions that

make us feel safe but don’t actually stop crime,” while being “smart on

crime” means changing the criminal justice system to “not just

incapacitate but rehabilitate.”

There

are other signs of progress. Last month, both chambers of the General

Assembly approved a bill to decriminalize possession of small amounts of

marijuana. Instead of being a criminal misdemeanor, it would be a petty

offense similar to a traffic ticket. That measure alone, if it earns

final approval from Rauner, could prevent a significant number of

offenders from entering the criminal justice system. However, the narrow

passage of the bill revealed that several Republicans and even some

Democrats in the legislature still have reservations about easing

criminal penalties, especially concerning drug use.

Even

if reforms sail through the legislature, some changes – such as beefing

up rehabilitation services – will depend on funding. Putting fewer

people in prison will mean the state spends less on incarceration, but

those savings won’t appear immediately. In light of Illinois’ perennial

budget crisis, that could mean parole and treatment programs remain

underfunded.

Despite the challenges facing reform, Samantha Gaddy, Rauner’s policy adviser on criminal justice, is hopeful.

“It

is very encouraging to see both sides come together on this issue and

discuss reform in terms of being ‘right on crime’ and ‘smart on crime,’ ”

she said, “instead of just being ‘tough on crime,’ which the data show

just isn’t effective in keeping us safe.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].