Compassionate response to victims gives them confidence to report

Julia Dixon only knew her attacker a few hours before her exciting new college experience became a nightmare.

It was her second weekend at college, and Dixon, then age 18, was watching YouTube videos with a group of new friends at her dorm. She wasn’t drinking or doing drugs, and she had shown no romantic interest in her attacker.

“It was the most benign social interaction I can possibly imagine,” Dixon recalls.

That didn’t matter. When Dixon went to her room to retrieve some candy her mom had sent, her attacker followed her and raped her in her own dorm room.

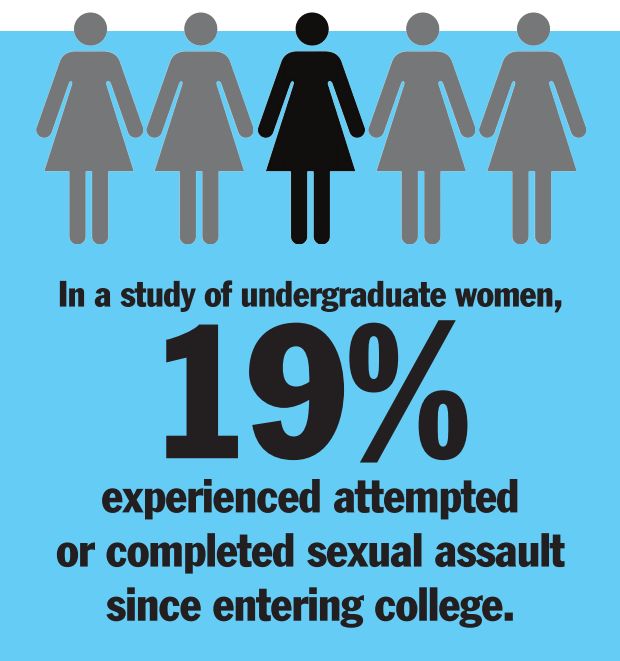

On college campuses across the nation, young women face the grim possibility of being raped or otherwise sexually assaulted. A 2009 survey commissioned by the U.S. Department of Justice revealed that 19 percent of women enrolled in undergraduate studies in the U.S. had been sexually assaulted or had been the victim of an attempted sexual assault. Considering that more than 8.6 million women attended undergraduate programs in 2013, it’s possible to extrapolate that roughly 1.6 million women in college were victims of sexual assault that year.

However, one would never know that from looking at the crime statistics gathered by colleges. The U.S. Department of Justice estimates that less than 5 percent of campus rapes or attempted rapes are reported by victims to law enforcement, and most colleges in Illinois and around the country report only a handful of incidents each year. Many report none. Although the federal government provides some guidance on handling sexual assault cases, schools often find it confusing, leading to uneven application. As a result, victims may be uncomfortable reporting their experiences and unsure about their rights and choices.

State lawmakers are considering legislation to help change that. A bill to standardize how schools handle sexual assault cases passed the Illinois House in April with strong support. The measure is aimed at combating the culture of rape that shames victims and too often fails to hold perpetrators accountable.

In Dixon’s case, she reported her rape to the local police department and submitted to a rape kit, the standard evidence collection procedure following a rape. She assumed the police would deal with her attacker and he would be out of her life within a couple of weeks. In reality, it was 20 months before she could begin to put the incident behind her. During that time, her attacker was free and continued attending the same university.

“I had no control over what he did during that time,” Dixon said. “I was trying to act normal and spectacularly failing at it. For me, it was almost two years of fear.”

Dixon’s attacker was eventually arrested and held accountable for his crime, but instead of being charged with rape, he pleaded guilty to a lesser crime and received a light jail sentence. He wasn’t required to register as a sex offender. Still, Dixon says that’s more justice than most victims receive. She says only two percent of rapists end up serving time.

In retrospect, Dixon wishes she had known about her rights, like the right to change her housing situation and the right to have a confidential adviser walk her through her legal options. Those rights are granted under Title IX, the federal anti-discrimination law for education, but many schools around the nation don’t follow the law. Dixon’s school wouldn’t even let her take her meals to her dorm room to avoid her attacker. She says she chooses not to publicly name the university – a public school in Ohio – to avoid giving the impression that the problem of sexual assault is confined to only certain schools.

Rolling Stone’s now-infamous story about “Jackie,” a pseudonym for a woman who alleged she had been repeatedly raped during a fraternity party at the University of Virginia, raised the issue of campus sexual assault to new heights of uncomfortable visibility in 2014. The magazine didn’t fully investigate Jackie’s claims in deference to what the author believed was a victim of a heinous crime, so when many details of Jackie’s allegations turned out to be implausible, it reinforced commonly held beliefs about rape victims making up stories for attention. Still, the story prompted several online commenters to share their own stories of being sexually assaulted at UVA and having their complaints brushed aside by the school.

Those commenters’ stories about UVA are hardly isolated to that school. Before the Rolling Stone article was published in November 2014, the New York Times ran

its own story in July 2014, detailing the story of a woman at Hobart

and William Smith Colleges in central New York. The woman in that story

reported her rape to the school, which subsequently found all three of

her alleged attackers – each a member of the school’s football team –

innocent, despite clear evidence of sexual contact and the victim’s

insistence that it was unwelcome.

The

U.S. Department of Education announced in May 2014 that it was

investigating whether 55 schools across the U.S. had violated Title IX

by failing to adequately respond to incidents of sexual violence or

failing to provide adequate protections against it. Two Illinois schools

- Knox College in Galesburg and the University of Chicago – are on the

list, which has since been expanded to 108 schools. A school may be on

the list due to a complaint or because of what the Department of

Education calls a “compliance check.” Asked for explanation, a

department spokeswoman sent an updated list of schools under

investigation but offered no further comment.

Under

Illinois law, sexual penetration under force or without consent is

called “criminal sexual assault,” the legal term for rape. It’s a Class 1

felony, carrying a mandatory sentence of between 4 and 15 years in

prison.

Proving rape

in the criminal justice system can be problematic, however. If the

victim wasn’t sober, the accused can claim that the victim consented to

the sex act at the time and has since forgotten. The accused can also

claim that the victim is lying about having given consent out of regret

or that the victim is trying to harm his reputation by spinning

consensual sex as rape. If a victim simply didn’t say “no” or didn’t

physically resist unwanted sexual contact, the accused can claim that he

interpreted her silence as consent.

Illinois

Attorney General Lisa Madigan held three public meetings on college

sexual assault earlier this year, speaking to survivors of sexual

assault and college administrators.

“I

don’t think there’s any question that sexual violence is at epidemic

levels on college campuses,” Madigan said in an interview with Illinois Times. “There’s

been a revolution across the country, because the response by colleges

and universities has been ineffective and devastating. I think we have a

legal and moral obligation to improve our response.”

What

Madigan and her staff found at the meetings is that many colleges are

unclear on their responsibilities regarding sexual assault. The federal

Clery Act requires schools to publish crime statistics and maintain a

daily log of crimes for public inspection, but many of the other

requirements for colleges come from a series of letters and

question-and-answer sheets published by the U.S. Department of

Education. The letters and answer sheets aren’t technically laws, and

many schools find them confusing.

Additionally, Madigan says victims of sexual assault often feel like no one is listening and no one cares.

“Sometimes,

if a school simply responds in a human way instead of a defensive or

even legalistic way, that resolution would occur so much better,”

Madigan said. “There would be a sense of ‘I was heard and provided with

the accommodations I needed, and I was able to move forward.’ ” Madigan

and Karyn Bass Ehler, chief of the civil rights division in Madigan’s

office, used what they learned in the meetings to craft legislation that

clarifies the federal requirements and standardizes how universities

across the state respond to sexual assault allegations.

Rep.

Michelle Mussman, D-Schaumburg, sponsors House Bill 821, which attempts

to provide victims with a safe environment to report incidents and

offer a fair process to investigate those claims. Mussman has worked

with Madigan’s office to shepherd the bill through the House.

Mussman

says women who experience sexual assault may not report it to

authorities for a variety of reasons. Besides the societal stigma that

comes with having been raped, young women may worry about whether

they’ll be believed. Drug or alcohol use can add a layer of uncertainty

in a victim’s mind about how much liability she may have had in the

incident.

“Girls

historically put a lot of blame on themselves,” Mussman said. “They

worry about having someone say they’re (making accusations) for

nefarious purposes, but I can tell you that this is not something

someone would choose to bring upon themselves.”

Julia

Dixon says she chose to report her rape because she didn’t know what

else to do. She understands why other victims choose not to report,

however.

“I am a piece

of evidence; my body is a crime scene,” she said. “My reporting was so

counterintuitive for a victim because you’re relinquishing a lot of

control. Your fate is up to a lot of people you don’t know. The last

thing you want to do after you’ve had control over your body taken away

is to give control to a bunch of strangers. Who would want to do that?”

If Dixon’s university had offered her more control over her day-to-day

life after the rape, giving up control to the justice system wouldn’t

have been so taxing, she says.

That’s

what Mussman’s legislation is meant to address. Under the bill, both

public and private schools would have to develop campus sexual violence

policies, including information like how to report incidents and how the

school will respond. Victims would receive notification of their

various rights and options, including the right to change their class

schedule or housing situation, how to obtain an order of protection and

their right to confidentiality. A trained adviser would be assigned to

help victims navigate their options and seek help, and schools would

have to train students and employees on how to respond to allegations of

sexual assault. Additionally, the bill would require each school to

adopt a process for investigating sexual assault allegations that is

fair to both victims and the accused.

The

bill passed the Illinois House with a 113-2 vote on April 22 and awaits

a vote in the Illinois Senate. Polly Poskin of Springfield, executive

director of the Illinois Coalition Against Sexual Assault, says her

group provided feedback to Madigan’s office on crafting the bill, and

she expects it to pass the Senate with broad support. Poskin says the

bill would mean increased accountability among universities, which she

believes often make decisions based more on legal liability than on

what’s best for victims of sexual assault.

“If

one in five women experience sexual assault but only 5 percent report

it, you’ve not created an accessible environment for the student to

report the most heinous crime short of murder,” Poskin said. “Something

has to shift inside universities. We’re not convinced they are

adequately informing students of their rights.”

Madigan

says the training mandated in the bill for students and staff will

especially make a difference for young women facing the daunting task of

trying to resume their lives. For example, the panel charged with

investigating claims of sexual assault must understand how to be

sensitive to the victim and must understand the effects of a traumatic

experience on a person’s memory. In situations where the victim was on

drugs or alcohol, there is training available to help police and

schoolappointed investigators determine whether the victim was able to

give consent at the time of the incident, Madigan says.

If

rape is a crime, why not send victims to local law enforcement agencies

to treat each claim as a criminal matter? Currently, schools aren’t

required to refer rape cases to campus police or local law enforcement

because the victim is allowed to choose whether to report the crime.

Mussman’s bill wouldn’t change that.

“If

a victim wants to go to law enforcement, they should,” Madigan said.

“But so many of the responses and the accommodations needed to go

forward with life are only going to be available through the college or

university.”Mussman says the cumulative effect of her legislation is to “create an

atmosphere in which people understand rape is not okay.” She especially

hopes to reach men in college, where the college lifestyle and the

pressure to be macho can sometimes override better judgment.

“It’s just important that we shed a lot more light on this,” she said. “These victims have remained quiet for a long time.”

For

the University of Illinois Springfield, the bill would essentially make

mandatory many things that the school already does. UIS spokesman Derek

Schnapp says the school has a sexual assault policy in place and

publishes an annual security report listing campus and community

resources for victims of crime. The university allows confidential

reporting of incidents and provides counseling services. Additionally,

the UIS Women’s Center functions as a place for sexual assault victims

to find a safe environment and information about their options. Besides

providing students with information on reporting sexual assault during

orientation, UIS sends campuswide announcements reminding students about

available support services throughout the year, Schnapp says.

UIS reported one forcible sex offense in 2012 and zero in 2011 or 2013. Data for 2014 has not been released.

Lt.

Brad Strickler with the UIS Police Department says the police host

“rape aggression defense” courses throughout the year, teaching

participants how to fight off an attacker. He says the course is

especially emphasized during the “Red Zone,” the time from August

through November when more than 50 percent of campus rapes occur.

Strickler also says part of his job is fostering a relationship with

students and university employees.

“We

try to make it a comfortable atmosphere,” he said. “I think most of our

students would tell you they feel safe, and we want them to feel open

and secure enough that they can come to us.”

Although

Julia Dixon, now age 25, is healing from her ordeal, she says it has

made her paranoid that other bad things could happen to her.

“We

talk about victims as survivors, but I definitely wasn’t a survivor

until my case ended,” she said. “For two years in college, I was a

victim. I almost miss being naïve. There’s so much safety and comfort in

waking up without knowing your life could be destroyed in a moment.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].