Lincoln’s scandalous nephew

Eugene Clover, married to Lizzie Edwards, killed a man in the Sangamon County Courthouse

HISTORY | Erika Holst

If

the Lincolns continued to take a Springfield newspaper even after they

moved to Washington, D.C., no doubt they would have been shocked by the

May 12, 1864, issue of the Illinois State Journal, which carried

the news that their nephew by marriage, Eugene P. Clover, had shot and

killed a Union soldier at the Sangamon County Courthouse.

It

wasn’t the first time Clover had shocked the family. On May 11, 1863,

he eloped with 20-year-old Lizzie Edwards, younger daughter of Mary

Lincoln’s sister, Elizabeth.

Clover’s

father, Lewis P. Clover, was not only the highly respected minister of

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, he was also an artist who had trained with

Asher B. Durand and painted a portrait of Abraham Lincoln in 1860.

Eugene, however, had some problems with alcohol – family friend Mercy

Conkling noted that “he seems not to have any friends except one or two

saloon keepers.”

The

Edwards family strongly disapproved of him as a suitor for Lizzie. While

visiting the Lincolns in 1862, Mary’s sister, Elizabeth, wrote home to

her older daughter, “Do persuade [Lizzie] to see less of Eugene Clover,”

adding hopefully, “she will never become seriously interested in him,

without, I have been grossly deceived.”

She

had been grossly deceived. Eugene and Lizzie ran away together on May

11, 1863. Her family was devastated – and furious. Three weeks after the

wedding, a neighbor commented, “The family are not in the least

reconciled to Lizzie’s marriage and take not the slightest notice of her

or Eugene, and say they never will.” A month later, they were still

giving her the cold shoulder: “Her father & Mother are not in the

slightest reconciled to Lizzie’s marriage yet, and [are] quite as

determined as ever to cut her off.”

One

year after the elopement, a sordid series of events went down in the

Clover family. While walking in downtown Springfield, Eugene’s

9-year-old sister, Bertha, was kidnapped by John M. Phillips, a soldier

in the 7 th Illinois Infantry. Phillips pulled her into his buggy and

drove her two miles out of town, where he tried to rape her. According

to the Clover family, the rape, “though attempted, was unsuccessful.”

Phillips drove her back to town and was soon arrested.

News

of the fiendish act swept through town like wildfire, leaving outrage

in its wake. At 8 o’clock on the evening of the attack, a crowd of

citizens seeking vengeance broke down the door to the jail with an axe.

The sheriff, however, had moved Phillips to a safe place, and cooler

heads prevailed on the crowd to let the due process of the law take its

course.

The next day

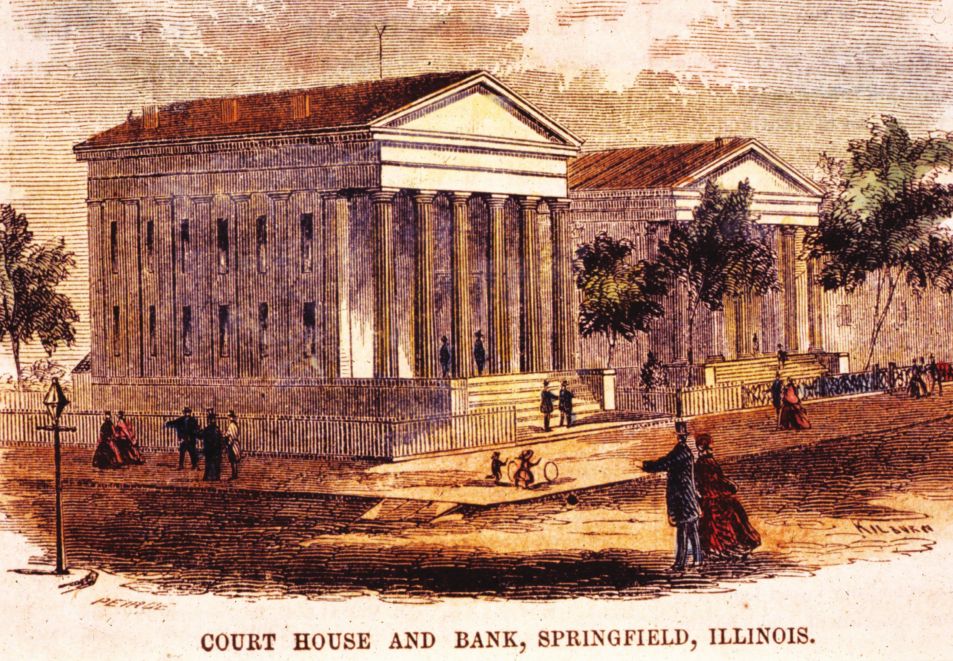

all hell broke loose. En route from his jail cell to the Sangamon County

Courthouse, Phillips was met with an angry mob that followed him into

the courtroom. As Phillips was standing in front of the judge, Eugene

Clover stepped forward and fired three shots from a large revolver, one

of which struck Phillips in the shoulder. Phillips ran to the other side

of the room and begged the crowd to spare his life, but, as the

newspaper reported, “the firing and the sight of blood seemed to madden

the crowd to the highest degree, and the court room soon resounded with

curses and cries of ‘hang him,’ ‘damn him,’ ‘shoot him,’ ‘kill him.’” A

length of rope was procured, and the cries of “hang him” intensified.

At

this point a local attorney, A. W. Hayes, jumped up on a table and

pleaded with the crowd to let the prisoner be tried for his crimes in

court rather than murdered in cold blood. His entreaty gave the sheriff

enough time to pull the wounded prisoner into a small room, close the

door, and send a message urgently requesting a military guard.

Meanwhile,

the crowd’s bloodlust reached a fevered pitch. Another revolver was

pressed into Clover’s hand, and he with the rest of the mob surged

toward the room in which Phillips was hiding. Hearing the advancing

footsteps and assuming they belonged to the guard, the sheriff opened

the door.

Clover fired

six shots in quick succession at Phillips, who was lying on a bench.

The only shot to connect with its target struck Phillips in the thigh

and caused him to fall face first on the floor.

At

long last a military guard arrived. He addressed the crowd, asking them

to return to their homes and assuring them that, should the prisoner

live, he would be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law.

The

prisoner didn’t live. The wound to his shoulder proved fatal, and he

succumbed to his injuries at about six o’clock that evening.

Eugene

Clover was charged with manslaughter but does not seem to have been

convicted. He and Lizzie went on to have two sons together.

At

some point, Eugene enlisted in the United States Cavalry. On Nov. 27,

1868, Clover’s cavalry regiment, led by George Armstrong Custer,

massacred a band of peaceful Cheyenne Indians on the banks of the

Washita River in the Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma). Clover was

killed in the attack. His body, later recovered, had been stripped,

mutilated, and decapitated.

Lizzie

Edwards Clover apparently mended fences with her parents, as census

records indicate that she and her sons moved back home after her husband

died. Lizzie and her kids were living in the Edwards’ house when Mary

Lincoln moved in after her stay at the asylum, and they were still there

when Mary came home to her sister’s house to die in 1882.

Erika

Holst is curator of collections at the Springfield Art Association. She

is grateful to Mary Beth Roderick for bringing this story to her

attention.