Killing bobcats

Is it time for Illinois to lift the ban?

WILDLIFE | Bruce Rushton

Bobcat hunting, Ron Edgerly swears, is about as much fun as a man can have in the woods. Just listen to him tell what happened when the quarry doubled back on its tracks in the frozen Gogomain Swamp in the upper reaches of Michigan.

“It was a cold year, 20 below zero,” recalls Edgerly, who started hunting bobcats when he was 13 and is still chasing cats as a septuagenarian. “I’m down on my hands and knees with my 12 gauge. This bobcat is running toward me, really coming on. The bobcat, all of a sudden, he jumped up into the air, 12 feet up off the runway.”

While the cat looked down from a tree, Edgerly’s two hounds sailed past, Wile E. Coyote style, intent on chasing down prey that bolted the opposite direction as soon the dogs were no longer behind it.

“The moral of the story is, my dogs were trained,” Edgerly boasts. “They probably ran that empty track 35 yards before they realized something was wrong. Within a halfhour, the two fast dogs caught him.”

Then there was the 40-pounder – huge for a bobcat – that Edgerly, then 73, bagged in 2012 without the help of dogs. He spent more than two hours tracking the cat through snow, then lured it into shooting range with the help of an electronic game caller that simulates the sound of a rabbit in distress. In addition to a pelt, he was rewarded with write-ups in newspapers and outdoor publications from coast to coast.

It is simple, really. All you have to do is find some bobcat tracks, guess where the creature might be headed, then set loose the hounds and keep up as best you can. If you don’t have dogs, stand next to a tree or climb up into an elevated stand, then stay absolutely still for an hour or so and hope that a cat fooled by fake rabbit cries comes along. Don’t worry about wind – unlike deer, bobcats don’t much care what the air smells like. But one tiny move and a bobcat, which relies on sight to hunt, will be gone. Edgerly swears they have 180-degree peripheral vision that extends to whatever might be above their heads.

“He’s stealthy, but he never gets in a hurry,” Edgerly says. “When it’s 20 below zero and you’re keeping silent and still, it’s pretty hard to stay warm no matter what you have on – to get cold, that’s just part of the game. The instant you see a bobcat, you warm up instantly. You’ve got to love the sport or you’re not going to do very well at it.”

Not everyone is so enthusiastic. Even Edgerly’s own son, raised as a hunter, no longer stalks bobcats.

“It is a lost art,” Edgerly bemoans. “It’s a dying, crying shame to see the young generation not having any interest in this. They’ve got their gosh darn cell phones and computers. Breaks my freaking heart.”

For cat hunters like Edgerly, who recalls bagging 23 cats in a single winter back in the 1950s, the good old

days are gone. The season bag limit in Michigan, he notes, has dwindled

from unlimited to one. But in Illinois, where bobcats have long been

protected, the door to hunting and trapping is starting to open. And not

everyone is happy about it.

A rebounding population

Former Gov. Pat Quinn is a bobcat’s best friend.

In

one of his last acts in office, Quinn vetoed a bill that would have

established a season for bobcat hunting and trapping. A ban on killing

bobcats that began in the 1970s, when the species was in serious

decline, was good for both people and bobcats, Quinn wrote in his veto

message, and lifting the ban would threaten the state’s ecosystem.

“To

subject the species to indiscriminate killing for recreational

amusement presents many serious risks and costs without much in return,”

Quinn wrote.

The

bobcat bill had sailed through the House on a 91-20 vote. The margin was

considerably smaller in the Senate, where it passed with just one vote

to spare and bobcats and their sympathizers left to wonder which way

nine senators who didn’t cast ballots might have gone.

“ It’s not the bobcat eradication bill. It’s the bobcat management bill.”

Sen. Sam McCann,

R-Carlinville, is sponsoring an identical bill this session. He says

that he loves cats and has a feline named Lily to prove it, but that’s

not the point.

“I was

asked by a group of constituents and the Department of Natural

Resources,” McCann says. “It’s not the bobcat eradication bill. It’s the

bobcat management bill.”

Whether

it’s blood lust or resource management, McCann’s bill is one of three

introduced so far this session to allow bobcat killing. Jen Walling,

executive director of the Illinois Environmental Council that lobbied

against the bill vetoed by Quinn, says that she’s optimistic that

bobcats will remain off-limits to hunters and trappers. The bill that

passed the Senate with a one-vote margin wasn’t debated in committee,

and so legislators didn’t get to hear from opponents, she said. The

council keeps a legislative scorecard, Walling said, and bobcat bill

vote tallies are included.

“We

had just started working on it,” Walling said. “I don’t see any of

those voting against it changing their votes. There are several

legislators who are aware they voted the wrong way.”

While

the measure ultimately failed, it was the closest the state has come to

having a bobcat season since hunting and trapping ended in 1972, with

the species being listed as “threatened” five years later thanks to

population decline. But notoriously elusive bobcats are rarely seen no

matter their numbers, and so deciding whether populations are at healthy

levels isn’t easy.

In

the seasons between 1966 and 1970, the Department of Natural Resources

tabulated approximately 1,100 pelts taken each year, suggesting that

bobcats were abundant, according to a 2002 report prepared by Southern

Illinois University researchers. Nonetheless, the state banned killing

them, and an SIU researcher later determined that the ban was a good

idea, given that just 89 sightings were reported between 1979 and 1982

in 52 counties. Researchers elsewhere postulated that intensive

agriculture in the Midwest had reduced bobcat habitat.

But

bobcats, like rats and whitetail deer, don’t necessarily mind living

close to people, and so the population climbed during the 1990s to the

point that cats were sighted in 99 of the state’s 102 counties,

including Cook County. The bobcat was removed from the state’s list of

threatened and endangered species in 1999.

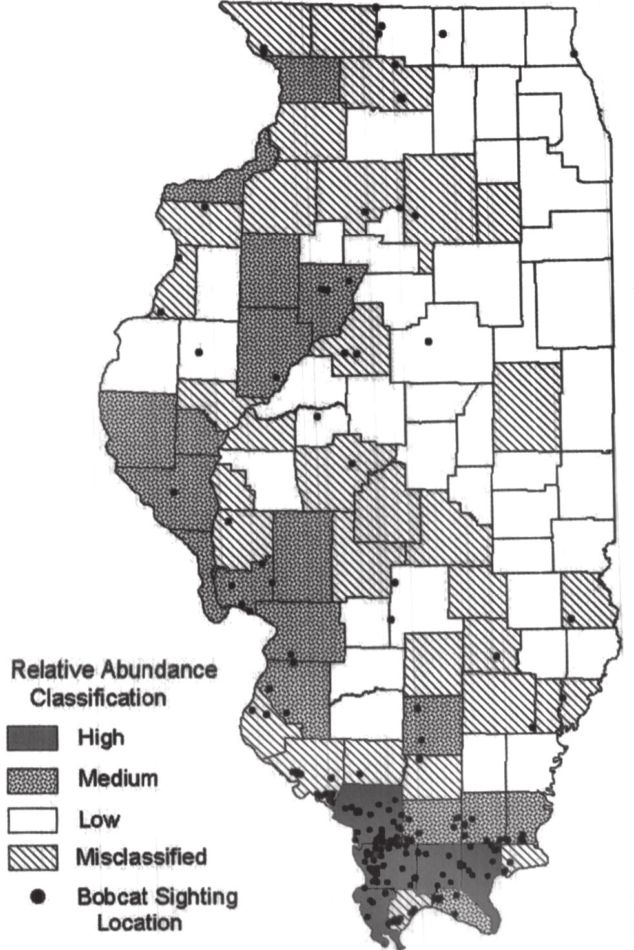

The

bobcat was delisted after SIU researchers trapped 96 cats between 1995

and 1999 and found them to be healthy, if not particularly clever –

several bobcats were trapped more than once, including one that was

captured seven times. Researchers put radio tracking collars on the cats

and also studied carcasses of dead ones felled by cars or natural

causes, finding full stomachs and little sign of disease. Nearly 30

percent of the state, mostly in the south, along the Illinois River and

in northwest regions, had suitable habitat for bobcats, researchers

reported, and patches of suitable habitat were scattered throughout the

remainder of Illinois.

“It

seems clear from the data now available…that bobcats are secure in

Illinois,” SIU researchers wrote 13 years ago in their study report

partially funded by the state Department of Natural Resources. “The

widely distributed population occurs at moderate densities…and there is

no biological reason evident to suggest that bobcats could not stand a

regulated, limited harvest in Illinois.”

Bobcats

are found throughout the nation, with fewer than 10 states requiring

that hunters and trappers leave them alone. In California, for example,

more than 1,000 bobcats are killed each year. Science, SIU researchers

predicted in 2002, would not decide the fate of the bobcat in Illinois.

“Certain

stakeholders will likely oppose any strategy less than continued full

protection from harvest in Illinois,” researchers wrote. “Any proposal

to initiate a season, however restrictive, to hunt and trap bobcats will

likely be opposed in public forums and by legal action. … Because

agencies such as IDNR require

public

support of their policies to effectively manage natural resources,

whether or not a bobcat harvest is ever allowed in Illinois will be

decided by public opinion rather than biological data.”

Killing and cruelty

The

Department of Natural Resources pegs the number of bobcats in Illinois

at between 3,000 and 5,000 – enough, department officials say, for

hunters and trappers to kill 300. Opponents note that the population is

concentrated in southern counties and that the bill vetoed by Quinn did

not specify where bobcats could be killed. That would be decided by the

Department of Natural Resources, which is backing a bobcat season.

“We

have this history where this animal was threatened and now it’s turned

into a success story,” says Walling, who is concerned that there are too

few bobcats, especially outside southern Illinois, to allow for a

hunting and trapping season. “Why can’t we wait until the population

recovers more?” Proponents of bobcat killing warn that the population

must be controlled or bad things will happen. There are fewer wild

turkeys than there used to be, some say, and bobcats are to blame.

Bobcats kill deer, others warn, despite scant evidence that cats that

typically weigh less than 20 pounds dine on venison with any regularity –

and never mind that deer are hardly at risk of extinction.

Trail

cameras have captured bobcats attacking deer, but whether such killing

is commonplace isn’t clear. SIU researchers found remains of deer in

just three stomachs of 91 dead bobcats, and it was impossible to tell

whether the cats had killed, or just stumbled across carrion. Mostly,

the cats were eating voles, rabbits and squirrels, researchers found.

“We’ve

had a small but growing number of complaints about bobcats, usually

with poultry,” says Bob Bluett, a DNR wildlife biologist. “At least in

the eyes of a lot of landowners and sportsmen, when you bring an animal

back, you have a responsibility to manage it. … We’ve relied on hunters

and trappers and landowners to make this a successful recovery since the

1970s. Now that we have a healthy bobcat population in the state, there

is interest in a harvest. In some people’s minds, we might have a few

too many.”

Neal

Graves, president of the Illinois Trappers Association, says that

bobcats don’t generate nuisance complaints because they’re nocturnal and

so rarely seen. He accuses bobcats of attacking fawns and threatening

the state’s deer herd.

“A bobcat kills just to kill,” Graves says.

“You

watch a domestic cat, it’s the same thing. Your bobcat will be really

bad on turkey and pheasant eggs, as will the coons. If you’re out in the

wild and you’re starving, you’re going to eat anything you can get your

hands on.”

Standing

motionless in frozen woods for hours on end, clutching a gun and hoping

for a bobcat to pass your way is one thing. Setting out a line of traps

and coming back tomorrow is something else altogether. And so opposition

to bobcat killing, at least for some, is inextricably tied to whether

trapping them is cruel. There is also the question of what happens to a

bobcat once it is dead.

“Nobody

eats bobcats – they’re hunted entirely for fur and trophies,” notes

Kristen Strawbridge, Illinois state director for the Humane Society of

the United States that is

fighting

bills to legalize bobcat killing. “This misguided legislation would

subject bobcats to cruel and unsporting killing methods, such as the use

of steel-jawed leghold traps and being chased down by packs of hounds.”

Then

again, all mammals might not be created equal. While the Humane

Society, the Sierra Club and the Illinois Environmental Council have

battled to protect bobcats, there was no such organized effort to

protect river otters, which were declared legal for trapping by the

legislature in 2011 after being successfully re-introduced into the

state with critters caught in Louisiana and sent north to the land of

Lincoln. Unlike bobcats, trapped river otters – the sort featured in

Disney films that cavort and play and slither happily down muddy slides

and into rivers just for the fun of it – are drowned by design in traps

that keep them submerged until the trapper returns. Trapped bobcats are

generally dispatched quickly.

Noting

that there are far more otters – the Department of Natural Resources

puts the number at between 15,000 and 20,000 – than bobcats, Walling

said the Illinois Environmental Council decided not to oppose the otter

bill after speaking with ecologists and reading population studies.

“They’ve done really well,” Walling said.

“We don’t oppose hunting.”

Strawbridge

could not immediately say why the Humane Society, which opposes leghold

traps, did not fight otter killing with the same vehemence that it has

opposed bobcat hunting and trapping. But surveys commissioned by the

state Department of Natural Resources have shown that public opinion is

against trappers no matter the animal.

Telephone

surveys conducted in 1994 and 2002 for the Department of Natural

Resources showed that fewer than 30 percent of state residents approved

of hunting and trapping animals for their fur, with fewer people

supporting trappers than hunters. In 2009, surveyors tweaked the

question by emphasizing that hunting and trapping are closely regulated

and found that approval increased to more than 70 percent, with many

respondents changing their minds after being told that the state

regulates harvests and requires that trappers younger than 18 complete a

trapping education course. However, opposition to killing for fur

remained high, with just three in 10 respondents in 2009 saying that it

was OK to hunt or trap animals for their fur as opposed to killing for

food or to prevent overpopulation.

Gripping questions

The

modern leghold trap is a far cry from jagged-jaw traps of yesteryear.

Traps with teeth that tear into limbs are now illegal, and many come

with offset jaws so that the business ends of the trap don’t clamp

tightly together, which allows some room for circulation. Wildlife

biologists use leghold traps to capture animals for study and for

relocation. Still, the stigma remains strong enough that eight states

have barred commercial and recreational trappers from using leghold

traps.

A video posted

on the National Trappers Association website shows foxes and other

furbearing animals waiting patiently for kindly trappers to free them.

Once let go, the animals scamper off, apparently unharmed, after

trappers rub their paws a bit, not unlike giving someone a wrist massage

after handcuffs come off.

“The

norm is for the animal to hunker down and wait,” the narrator intones.

“Some drop off to sleep. … The experience is not much different from the

restraint of a pet dog with a leash or tether, only the animal is held

by the foot, not the neck.”

It

would be a more convincing demonstration if the trappers had put their

own hands in traps, an idea that wasn’t encouraged during the Illinois

Trappers Association annual fur auction in Fairfield last month.

“I

wouldn’t suggest doing that,” a trapper advises when a neophyte asks

about putting his finger in a trap intended to capture raccoons. Another

warns that the raccoon trap likely carries enough power to snap a

pencil in two.

There

is no shortage of fur at the auction held at the Wayne County

Fairgrounds in Fairfield. It takes nearly seven hours to auction off

hundreds of hides from beavers, otters, foxes, raccoons and other

oh-so-soft animals. No one is getting rich. The 14 buyers present rarely

pay more than $30 for a pelt, with prices of less than $10 being the

norm, depending on the species and quality of fur. The concrete floor of

the unheated building is covered with plastic so that oils from the

untanned, or green, hides can’t leach into the concrete and leave behind

spots. A local service club sells chili.

“You do it because you love the outdoors,” Graves says. “All we are is a tool to help keep our wildlife in balance.”

Many

of the pelts will end up overseas, particularly Russia, China and

Korea, and so outdoorsmen – and they are virtually all male – at the fur

auction are keenly aware of the strength of the ruble, the direction of

the oil market and the coldness of the winter in countries thousands of

miles away. They also know that Illinois has come closer than ever

before to legalizing bobcat

trapping.

And they’re optimistic that Gov. Bruce Rauner, who professed himself an

outdoorsman on the campaign trail, will see the bobcat issue

differently than his predecessor.

These

guys spend a lot of time in the woods, and they say they started seeing

bobcats and bobcat tracks as far back as eight years ago.

“I

thought it was a coyote to start with,” says Jeff Merrick of Geff, who

saw his first bobcat four years ago while turkey hunting. “It raised its

tail and I saw white. I thought I was seeing things.”

There are two bobcat pelts for sale, one from Tennessee, the other from Kentucky, and interest is high.

“Is

there another one?” someone asks after the pelt from Kentucky sells for

$87.50, the highest price paid for any pelt the entire day. “Where did

that bobcat come from?” another person demands. “Is that a big one?”

someone else wonders.

Chane

Lyons of Sandoval, who both traps himself and buys fur to resell at

larger auctions, figures he paid more for the Kentucky bobcat pelt than

it was worth, but that’s what novelty will do. This pelt, he says, will

end up on a wall at his house.

Lyons

says that he’s trapped and released several bobcats while seeking

coyotes, once finding four in a single day. The way he figures it, the

chances of a bobcat bill passing are good, and so the days of freeing

bobcats caught in traps are coming to an end.

“I think it will eventually come into law,” Lyons says.

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].