HISTORY | Tara McClellan McAndrew

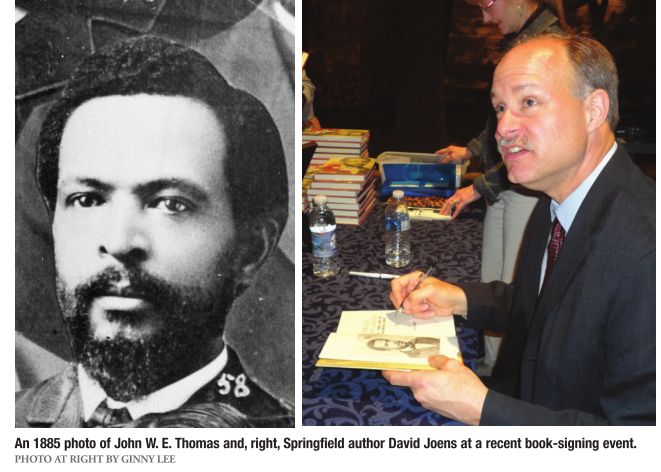

From Slave to State Legislator: John W.E. Thomas, Illinois’ First African American Lawmaker, by David A. Joens. Southern Illinois University Press, 2012. 288 pages, $34.95.

In 1877, Illinois became the first state in the Midwest and only the second state in the north to send a black man to its state legislature. That man, John W. E. Thomas, was Illinois’ first African-American legislator and he had a special relationship with Springfield.

Thomas was a former slave who had moved in 1869 to Chicago, where he became a teacher, a real estate investor and later an attorney working in the police courts. Thomas also became a leader in the African-American community, which had received the right to vote a year after he arrived in Chicago. It used that vote to send Thomas, a Republican, to the Illinois House of Representatives in 1877, in 1883 and again in 1885, where he successfully passed the state’s first civil rights legislation and helped pass election reform and other good government measures, despite obstacles.

Sadly, Thomas’ accomplishments are littleknown, but a new book by Springfield resident Dave Joens changes that. From Slave to State Legislator: John W. E. Thomas, Illinois’ First African American Lawmaker, published this year by Southern Illinois University Press, chronicles Thomas’ interesting story.

“Thomas always knew he was the first African-American legislator in Illinois,” Joens says. “He was always made aware of that, and I think this had to weigh heavily on him. He knew there would be some animosity toward him, so he had to behave himself accordingly because he wasn’t just a state representative, he was there representing his entire race.”

During his first term, Thomas was called on by the House speaker to take the speaker’s position temporarily. “Democrats from southern Illinois began to congregate in the back of the chamber and loudly voice their indignation,” writes Joens.

Another day, Rev. George Brents, an African-American minister from

Springfield, opened the day’s session with a prayer. Hours later a

downstate Democratic lawmaker submitted a resolution to bar

African-American ministers from giving the daily prayer. The speaker

immediately deemed it out of order.

Besides

discrimination, Thomas faced challenges from internal party politics.

During his tenure, Illinois’ African-Americans, who were largely

Republican, became disenchanted with the party for not giving its

community more patronage and political opportunities. Thomas remained a

loyal Republican despite these issues and, while that didn’t always sit

well with his African-American peers in Chicago, it was a different

matter downstate.

“Thomas

got to know Springfield pretty well, and he was well liked here,

especially in Springfield’s African-American community,” Joens says.

It

helped that Thomas spent a lot of time in the capital city. “For three

legislative sessions, he was in Springfield at least six days of the

week for six months of the year,” Joens adds. Thomas was here for other

events as well, including conventions of the state’s leading African-

Americans and state Republican meetings.

Thomas became such good

friends with one Springfieldian that his daughter was born in the man’s

house. That man was Rev. L.A. Coleman, minister for Springfield’s Union

Baptist Church (founded in 1871 and still thriving). Active with his

home Baptist church in Chicago, Thomas met him through a coalition of

African-American churches.

Rev. Coleman lived at 438 N. Fourth St.

and

had Thomas stay with him during the 1877 and 1883 legislative sessions,

according to Joens. During the spring of 1883, Thomas’ wife, Justine,

was pregnant and “very fragile.” Thomas couldn’t leave the legislative

session to be with her in Chicago, so he had her come to Springfield.

She gave birth to their daughter on April 4 at Rev. Coleman’s house.

Sadly, both she and their baby died within weeks of each other.

Despite

his double loss, Thomas returned to the legislature only “five days

after his wife’s death and just three days after his daughter’s,” Joens

writes.

In 1885,

Thomas successfully sponsored the state’s first civil rights

legislation, mandating that all Illinoisans were “entitled to full and

equal enjoyment of public accommodations or places of amusement.”

Violators were required to pay their victims a penalty ranging from $25

to $500. After the General Assembly passed it that June, Springfield

African-Americans celebrated in the Illinois Senate chambers. At the

celebration, which Thomas attended, “a Springfield African- American man

named James Young introduced a resolution thanking Thomas for his

efforts at passing the bill and called him ‘our legislator,’” Joens

says.

A Springfield black man followed Thomas’ footsteps into the legislature. Shadrach Turner was a correspondent for the Cleveland Gazette, an

African-American newspaper based in Cleveland. He wrote favorably about

Thomas and his passage of the civil rights legislation. Later, Turner

started an African-American newspaper in Springfield, then moved to

Chicago and was elected to the legislature.

In 1899, Thomas died at his Chicago home at the age of 52.

Contact Tara McAndrew at [email protected].