By then, funeral directors who later became plaintiffs were worried. Their first inkling that something was amiss had come in the fall of 2007, when the comptroller’s office revoked the IFDA’s license, saying that it should never have been issued in the first place and that the trust needed to be in the hands of a properly licensed fiduciary. Under state law, funeral directors would have to pay for funerals themselves if the fund went kablooey, and money from more than 40,000 consumers was in the trust.

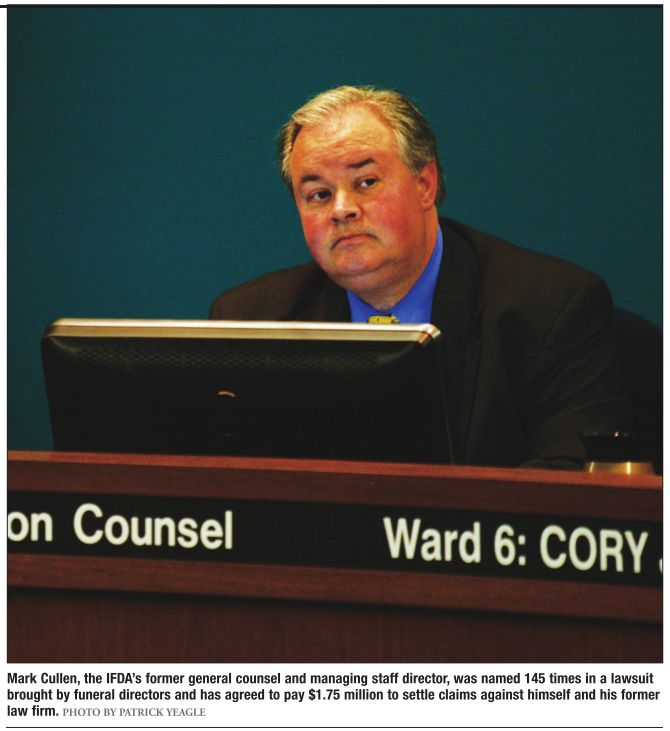

Concerned funeral directors met with Cullen three times in June, 2008. When directors demanded that their money be transferred to Regions, Cullen told them that the association would release funds only if they signed forms releasing the association’s officers from liability, funeral directors say in court papers.

Funeral directors backed off on their demands that the IFDA transfer their money when the association’s president asked them to “stand down” and said that an actuarial firm would analyze the fund and deliver findings so that funeral directors could know the true state of the trust and its prospects. But funeral directors say they never got the promised findings.

End game

In late 2008, the IFDA finally transferred trusteeship to a licensed fiduciary: Merrill Lynch’s trust division.

The investment giant that had sold the association on life insurance as an investment tool began liquidating the insurance policies, and the value of the fund was written down by $59 million.

The scandal turned public in early 2009, when newspapers reported on the first lawsuit filed by funeral directors against the association, Merrill Lynch and Cullen. Alerted by the media, the Secretary of State stepped in and suspended Schainker’s license to sell securities and give investment advice.

With funeral directors fretting about bankruptcy, the Department of Insurance, which had been a division of the Department of Financial and Professional Regulation, fined Schainker $100,000 in 2009, the maximum allowable penalty, and reached a settlement with Merrill Lynch, which admitted no wrongdoing but agreed to pay $18 million to funeral directors. But there was a catch.

To get the money, funeral directors had to agree to release Merrill Lynch from future liability. Directors refused and sued the comptroller, the Division of Insurance and Merrill Lynch, ultimately winning their case and forcing the state and the investment company to drop the requirement that would have prevented them from seeking more money via lawsuits.

Thanks to private attorneys and the Secretary of State, a lot more money came, but it took three years to calculate losses.

“It was complicated,” says David Finnegan, senior enforcement attorney with the securities division of the Secretary of State. “We wanted to make sure the analysis was done correctly.”

From the start, the Secretary of State’s office vowed that it would force Merrill Lynch to make the fund whole. While there have been at least three analyses of the fund to determine the size of the deficit, the Secretary of State required Merrill Lynch to pay for another study that included an actuarial analysis.

“We’re professionals here,” Finnegan said.

“We weren’t going to rely on other studies, so I didn’t look at them.”

Over the years, the life insurance arm of Merrill Lynch received more than $32 million in premiums from the IFDA, according to the Secretary of State’s consent order, and the arm that sold the policies collected nearly $7.2 million in commissions. Between lawsuits and agreements with the government, Merrill Lynch will pay more than $55 million to funeral directors who had money in the association’s pre-need trust.

Finnegan said the investment firm was “very cooperative,” although there were some “frank discussions” when the analysis was complete and

his office demanded a payment that assumed the most conservative return on investment.

“We could revoke their registration in Illinois – that could have a huge impact in Illinois, that could also reverberate across the country,” Finnegan said. “It was always out there. Because of their cooperation, it wasn’t something we discussed with them.”

Bill Halldin, Merrill Lynch spokesman, wouldn’t say whether the scandal has prompted the company to change its business practices.

“Our focus in our discussions with the state and other parties has been on ensuring that consumers receive the services that they paid for,” Halldin said.

The state has revoked licenses to provide investment advice and sell insurance and securities that were held by Schainker, the former Merrill Lynch broker credited as the architect of the failed trust.

Dale Kurrus, who runs a Belleville funeral home that was a plaintiff, said he didn’t want to discuss the saga in detail.

“It’s a touchy subject for everybody,” Kurrus said. “I’m just glad all this is behind us.”

Aftermath

Funeral directors whose money was at risk say that the failed trust constituted a crime. State Rep. Dan Brady, R-Bloomington, who is a funeral director, notes that any violation of the state Burial Funds Act is a felony.

The act puts strict limits on management fees, and the comptroller’s office has said that the IFDA exceeded those limits by $9.6 million. The act also says that consumers must be notified and give consent before their money can be spent on life insurance, but no one told purchasers of pre-need funeral plans that their money was going toward insurance premiums.

“The question still begs: Was there a criminal offense here?” Brady asks.

In 2009, the U.S. attorney’s office in Springfield served a subpoena on the comptroller’s office, demanding records on the IFDA, but there has been no further sign of prosecution. In a federal report on the funeral industry issued in December, the General Accountability Office wrote that Illinois regulators were still trying to determine what, if any, charges should be filed.

State officials point fingers when asked why criminal charges haven’t been filed. Natalie Bauer, spokeswoman for attorney general Lisa Madigan, said that the question is best addressed to the comptroller, given that the comptroller’s office is the agency charged with administering the Burial Funds Act that proscribes criminal penalties. In an email, Bradley Hahn, spokesman for comptroller Judy Baar Topinka, said the question should be put to the attorney general. Asked directly via email whether the comptroller has asked for a criminal investigation, Hahn did not answer.

“As the attorney for the state, the AG’s office would be the most appropriate place to address any potential criminal prosecution,” Hahn wrote.

The state first alleged that the IFDA had taken excessive fees from the fund in 2006, but regulators have not recovered the money. When the association sued the comptroller in 2009 in Cook County, asking a judge to declare that it shouldn’t be required to pay anything, the comptroller countersued. The case is pending.

Hahn in his email said the state is working out a settlement.

“The comptroller’s office is confident that it will have a favorable settlement to announce in the near future, but terms remain confidential pending a final agreement,” Hahn wrote.

The GAO report included an appendix devoted to the way Illinois regulates funeral sales and cemeteries, and the IFDA scandal is prominent. The GAO reported that there was $300 million invested in pre-need funeral trusts in Illinois as of last June, but the comptroller’s office is still having trouble regulating the pre-need industry.

“Officials representing the Illinois Office of the Comptroller stated that they are very limited on the types of disciplinary actions that they can take against licensees,” the GAO reported. “For example, to revoke or suspend a license is slow and the proceedings are very costly.”

Hahn said that Topinka retained two hearings officers last June who are working to create a license revocation system and expects to start revocation hearings this month for funeral homes that break the rules. While Brady says the comptroller’s office should stop regulating the funeral industry and cede all authority to the Department of Financial and Professional Regulation, Hahn says that Topinka, after consulting with funeral home operators, thinks the power should stay with her.

“Based on her interaction with the industry and the fiscal nature of her position, the comptroller believes that the pre-need industry is appropriately within her regulatory purview,” Hahn said in his email.

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].