By mid-1988, Tom’s quickly-growing repertoire of excellent material could only be heard by visitors to his weekly open mic sets, effectively raising the bar for the other open mic participants to an almost impossibly high level. One such participant was Springfield-based guitarist and songwriter Jim Schniepp, who in 1988 was laying the groundwork for his own band, Backwards Day. He became a regular performer at the Sunday night open mic at Union Pub, where Tom’s weekly sets contained offhand but spellbinding performances of now-perennial Irwin compositions such as “Fundamental Differences” and “The Crystal Palace.” When repeated suggestions that Tom book studio time to record the songs for posterity fell on deaf ears, Schniepp decided to take matters into his own hands.

One night in February of 1989, Schniepp invited Irwin to bring his acoustic guitar to a small apartment on the west side of Springfield, with the express intention of recording an album worth of songs. Two microphones, a Tascam brand 4-track cassette recorder, and a bottle of wine were the only additional accoutrements required, and a few hours later, basic tracks were in the can. Soon, eleven of those songs were released as the cassette-only Cornucopia, via Backwards Day’s Rickety Rackety Records imprint. With his first solo release in hand, Tom was fully re-energized and 1990 found him breaking out of his rut.

He started playing higher profile gigs and formed the first of many backing bands. The Cornpickers were practically an all-star outfit for Springfield, featuring NIL8 bass player Bruce Williams and ace drummer Tony Berkman from Condition 90 along with Brad Floreth on keyboards. The combo soon released Under a Maybe Moon, a rocking and expansive follow-up cassette to the strippeddown Cornucopia. On Moon, the band format allowed Tom to extend his range considerably, adding the upbeat “Stood Up,” the darkly topical “Markadee Kelly” and the avant-garde proletarian wackiness that is “Workin’ Jerk” to his already dependable stock-in-trade of alternately wry and heartrending ballads.

“My idea back then was, I’m gonna put an album out every year, whatever happens,” says Irwin. “But after a couple years, it got to the point where I realized I didn’t have the money to do this, they’re not selling, so it slowed down some. Randy Royce helped me do Roots in the Earth in ’93 and I still was writing a lot then.”

Tom’s skills as a songwriter and performer have only deepened in the intervening 20 years or so, and he has also experienced a considerable amount of personal growth, earning his master’s degree at UIS and raising his three sons, John, Sam and Owen, all while supporting himself primarily via his music, a remarkable feat in itself. Still, in many ways he has settled into a comfortably repetitive routine since the mid-’90s, with his dependable weekly gigs and presence in IT causing many in Springfield to take him for granted, as much a part of the music scene as the Hilton in the local skyline.

This state of affairs is starting to change with the ambitious Sangamon Songs. The new project has garnered a considerable amount of attention outside of the immediate area. He has been interviewed about the record by the American Public Media radio show The Story http://tinyurl.com/7az5xft. In fact, the recording of Sangamon Songs itself was funded via kickstarter.com, a self-described “funding platform focused on a broad spectrum of creative projects.” Through the website, Sangamon Songs received $4,602 in donations from individual music fans, more than $1,000 more than the projected $3,500 budget needed to record it.

“The most success I’ve had with this, already, has been from people who never even heard the record yet,” Irwin points out. “It’s getting more attention than I’ve ever gotten in my life, and it’s the story about the diary that gets people interested. But I do think the music will bring them in, too, once they’ve heard it.”

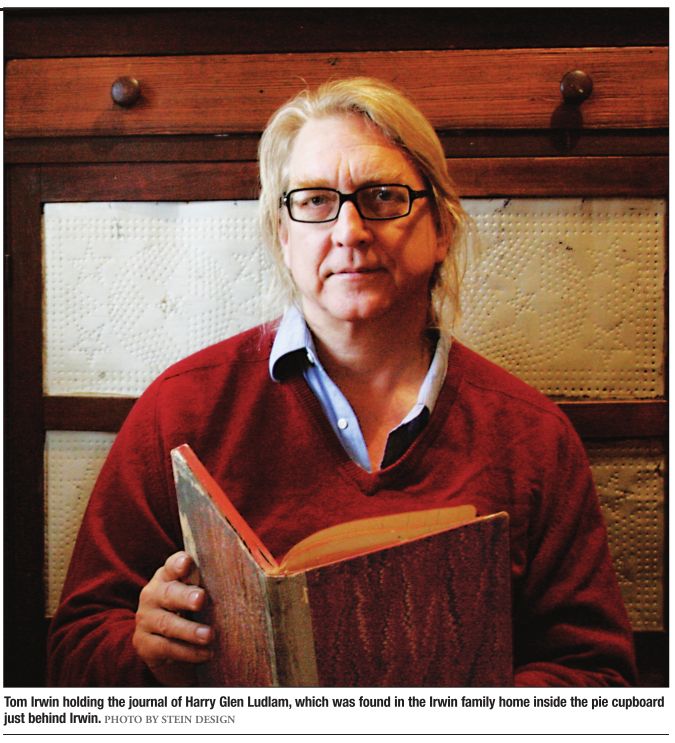

Indeed, much has already been made of the fact that the bulk of Sangamon Songs is essentially a collaboration between Irwin and longdeceased Harry Glen Ludlum, the young farm boy whose 19th century diary was discovered on the Irwin family property. At times the process is almost abstract, such as the song inspired by a journal entry where young Ludlum offhandedly observes, after a visit to church, that “it is moonlight now.” “That song kind of came out of nowhere,” says Irwin. “It started with that one line and I just kind of let it come out. In all of the songs, some of Ludlum’s words I used directly and other ones I didn’t but it was always that idea.”

Irwin continues with his Sunday gigs at Brewhaus, where he is normally backed up by the no-nonsense Raouligans, named after Irwin’s longtime bandmate and running partner, the late Scott “Raoul” Neese, a character so much larger than life he practically demands his own article. The band consists of Bruce Williams on bass, Timothy “Grumpy” Harte (ex-Backwards Day) on drums and Irwin’s oldest son, Owen, providing fiery lead guitar. In contrast, Sangamon Songs has presented a variety of fresh promotional and performing opportunities, including some uniquely theatrical ideas. “We’re doing a thing out at New Salem on July 7 where we’re gonna maybe let John [Irwin’s teenage son] sing some of the Harry songs and even do some staging for it,” he explains excitedly. “Somebody even said, ‘You could make this into a musical,’ and maybe that’ll happen someday, I don’t know. Or Sangamon Songs II could come out sometime.”

“I guess it’s possible that I could have done something like this 25 years ago,” says Irwin, “but it does feel like I’ve been waiting for my ability to write songs to improve enough to tackle this material. This is not the end of my songwriting by any means. I’ve already started some other songs, but it does seem to me that I ended up in a really good place, where I could use everything I worked on for years as far as writing songs, and all the topics that I’d always wanted to write about, and put them in a different sphere, where it’s not so self-involved. In a sense Sangamon Songs is closer to a novel, because so much singersongwriter stuff is so focused on yourself, kind of ‘Oh I stubbed my toe, I’m gonna write a song about it,’” he snickers.

Woolsey is even more circumspect when it comes to his friend’s career. “One of the contentions I always had with Tom was, and is, that he has never been a very good self-promoter,” he says, bluntly. “I think he’s right on the cusp of that now. I mean, just from being in a town this size for so long, he does have that contingency of, well, you can’t call ’em fans, but onlookers, who seem to relish the fact that he hasn’t struggled farther along than where he is. So many times it seems like he’s right there, over the pool, standing on the diving board. And sometimes he has taken that leap of faith and there’s been no water. I don’t think he’s been given his just due, just yet.”

Scott Faingold has known Tom Irwin since 1984, and first wrote about music for IT in 1987. He was a co-founder of the band Backwards Day, and is the author of the novel Kennel Cough, a fictionalized portrayal of the Springfield music scene.