“My perception, from where I sit, is that community-based services aren’t available in the quantity or the quality that are necessary to maintain a lot of these kids, and that’s why it all breaks down,” Schornagel says. “All of the agencies that I’ve worked with have been, over the years, trying to back away from residential placement and take some of the money they were spending on residential care and redirect that to community-based programs. It’s a slow process of moving the money from the back end to the front end, and I think we’re in the middle of that.”

Marlowe says more community-based services are a big part of the solution, but families must also be prepared for the challenges they will face when adopting.

“All of us in the field believe that if we build a stronger safety net, we will be seeing fewer family crises,” Marlowe says. “The system as a whole is trying to move from a mode of reacting to crisis to a more preventative approach. But not every family’s problems can be solved by Dr. Phil in 60 minutes like on Oprah. Growing into a mature, healthy adult is a process that requires support from family at every turn.”

Too little, too late

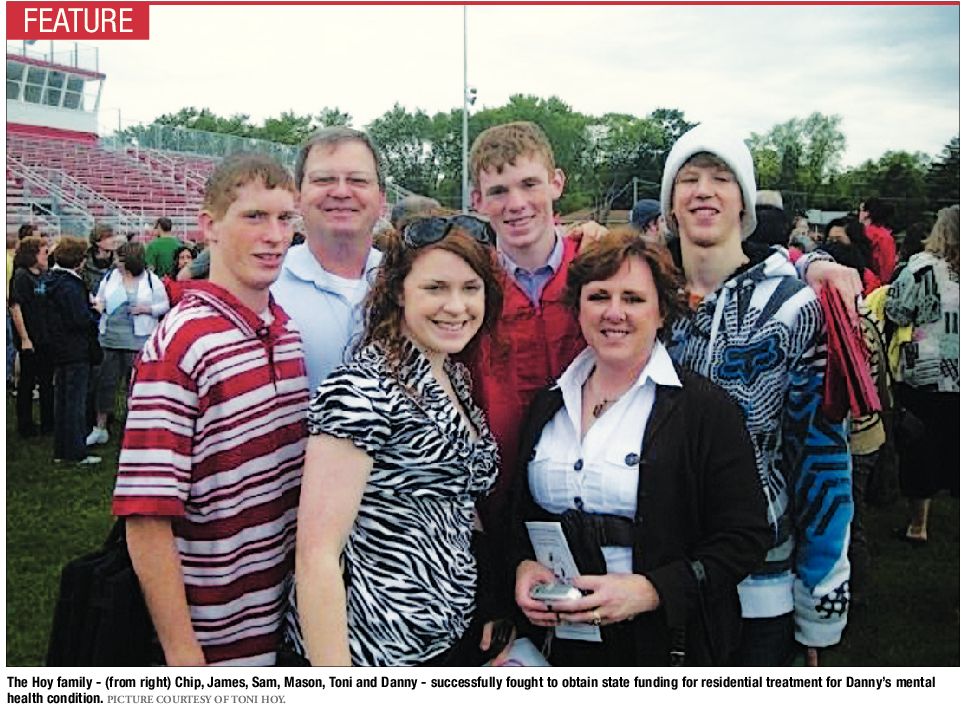

But for families already in crisis, it’s too late to build a stronger safety net. In 1998, James and Toni Hoy of Ingleside, Ill., adopted a two year-old son named Daniel. He displayed developmental delays, had been abused by his biological parents, and had been born under the influence of drugs and alcohol. As Daniel grew older, he began to display violent and aggressive behavior, which became dangerous enough that Toni Hoy says she didn’t feel safe in her own home.

The Hoys tried several methods of therapy and counseling for Daniel, but nothing seemed to work. The final straw was when Daniel, then 13, pulled a knife on one of the Hoys’ other children and threw another child down some stairs.

In 2007, they approached the Department of Human Services (DHS) and the Department of Healthcare and Family Services (HFS) about paying for $180,000-per-year residential treatment the family could not afford.

The state declined to pay.

Denied funding for treatment they felt Daniel truly needed, the Hoys chose not to pick him up from the psychiatric hospital. Like the Buschs, they faced a charge of neglect for their psychiatric lockout, and their son became a ward of the state, which eventually placed him in a residential treatment facility.

The Hoys eventually got the neglect charge dropped, but it remained in the State Central Registry of abuse and neglect findings. They sued DHS and HFS to obtain funding for Daniel’s residential care, settling their case in July 2011 with an agreement that the agencies would pay for Daniel’s treatment while not admitting any fault. The Hoys also regained custody of Daniel, who is now 16 and was recently transferred from residential care to a

juvenile detention center for assaulting a teacher and damaging a car.

While the Hoy case doesn’t set a precedent for other cases because it was settled before a court ruling, Toni Hoy says she has advised several other families in similar situations, and their case may serve as a catalyst for an upcoming class-action lawsuit.

The Collins Law Firm in Naperville, which represented the Hoys in their case, is examining similar cases to construct a class-action suit that could force changes in how the state handles psychiatric lockouts, custody relinquishment and residential care. Attorney Aaron Rapier at Collins says that suit is still in the planning stages and will not be pursued until later, to avoid jeopardizing the Hoys’ settlement.

In the meantime, John Schornagel at CRSA says the state’s financial woes limit the speed at which agencies can move from reacting to crises toward preventing them.

“State agencies have all been cut back on a variety of services – administration and direct services – and a lot of the nonprofits that do the heavy lifting are in trouble because the state isn’t paying their bills in some instances and they’re cutting back on services they provide to the community,” he says. “It makes being proactive more and more difficult. … I don’t think there’s any bad guys here. The agencies are doing what they can to do a better job with a very, very challenging population. I think they’re beginning to win the war, but there’s always casualties.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].