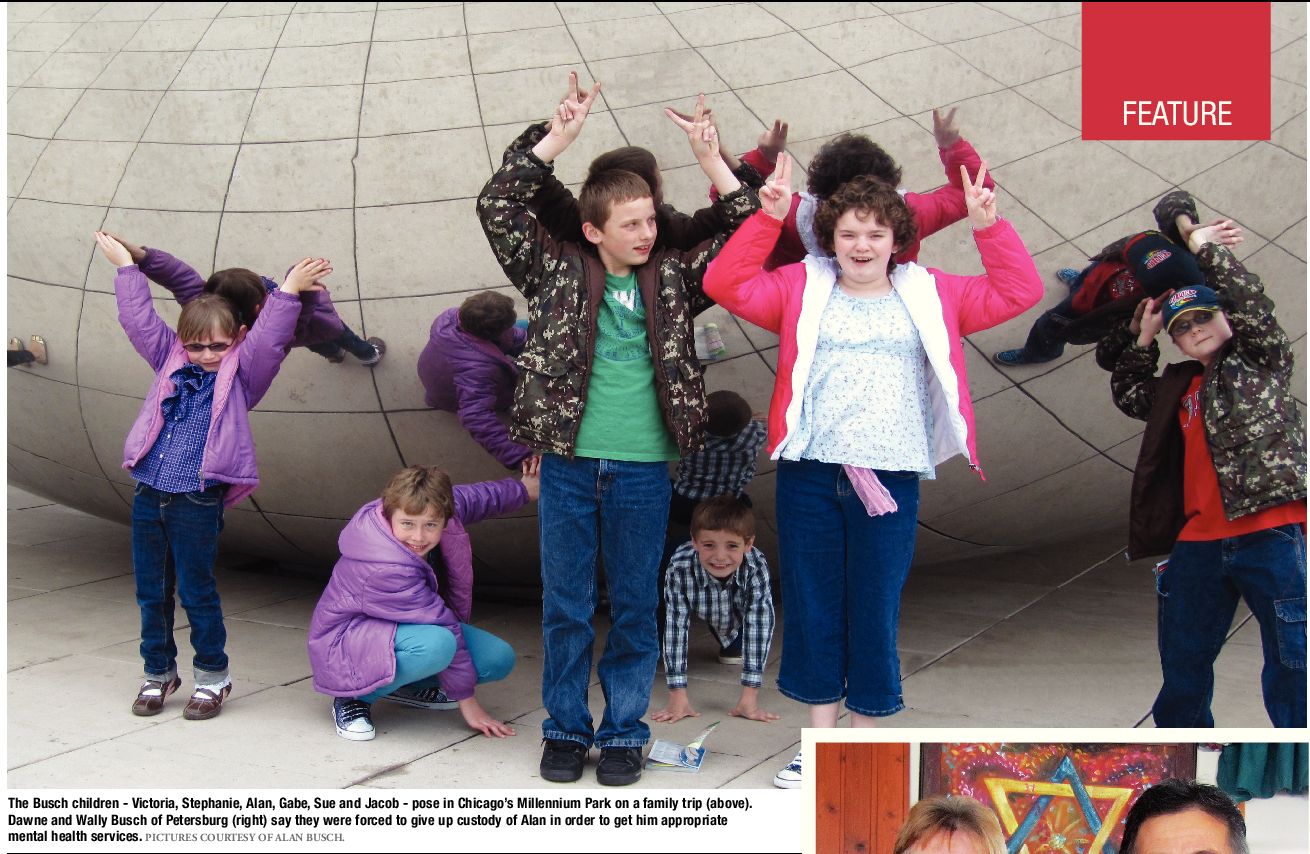

Giving up custody to get kids the mental health care they need

HEALTH | Patrick Yeagle

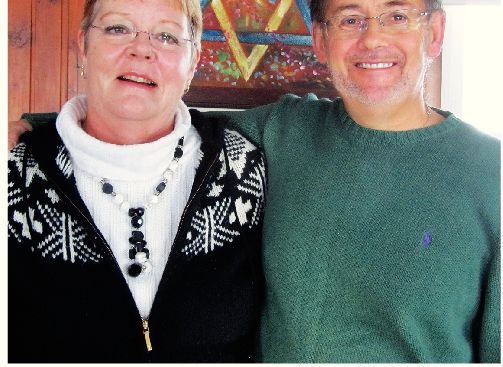

Wally and Dawne Busch of Petersburg eagerly adopted their son Alan at the age of two in 2000, knowing that they would be in for some challenging times. They knew that Alan, now 13, had been abused by his biological mother, and they weren’t surprised when, around the time he hit puberty, he began to develop severe emotional and behavioral issues, which often manifest in violent outbursts, threatening Alan’s safety and that of everyone around him.

He threatened to kill other children at school, threatened to hurt the couple’s other children, mutilated his own body and talked often about killing himself. But the Buschs say their most troubling challenge hasn’t been Alan’s behavior. It has been trying to help their son in an environment that they say pushes

families to give up custody of children to the state in return for mental health services.

The Buschs adopted Alan and his sister, Stephanie, with assurances from DCFS that the state would pay for the children’s medical needs, including mental health care. Despite counseling and therapy, Alan’s behavior became too dangerous for the family to keep him in their home, according to Wally Busch, so in October 2010 the family had Alan committed to a short-term psychiatric hospital with plans to send him to a long-term residential care facility at his psychiatrist’s recommendation.

Lacking the hundreds of thousands of dollars needed to pay for Alan’s treatment, the Buschs approached DCFS about paying for long-term care, but the agency declined.

After Alan spent a week in the psychiatric hospital, the Buschs received a call saying he was ready to come home – that he was no longer a danger to himself or others. Fearing for the safety of their family and of Alan himself, the Buschs took their attorney’s advice and decided not to pick Alan up from the psychiatric hospital. DCFS charged them with neglect, classifying the Buschs’ choice as a “psychiatric lockout.”

The neglect charge against the Buschs was dismissed in court, but their choice to not bring Alan back home essentially meant they had given up custody of Alan to the state. He remains in state custody at a residential treatment facility, though the Buschs retain parental rights such as visitation.

Custody relinquishment The Buschs’ story is typical of a situation called custody relinquishment. It involves an adoptive family becoming overwhelmed by the challenges of a mentally ill or emotionally disturbed child. Usually after trying several methods of counseling and therapy that don’t seem to work, the family decides that expensive longterm residential care is the only option left, but securing funding from the state proves difficult or impossible. The family then decides the only option to secure treatment for the child is leaving him or her in the hands of the state. The decision to “lock out” a child usually comes at the suggestion of a family’s attorney, psychiatrist, or even a state agency, but it often results in the family losing custody of the child.

continued on page 12