Mercy offering new radiation therapy

JANESVILLE

Some cancer patients might not think of the physicist who is helping in their treatment.

But the addition of a physicist and an experienced radiation oncologist last year at the Mercy Regional Cancer Center is opening the door to state-of-the-art radiation treatment.

“Lots of the critical stuff isn’t talked about, and (it’s) behind the scenes, like really high-quality physics and quality-assurance methods,” said Dr. Kevin Kozak, radiation oncologist.

Kozak soon will use advanced methods to treat tumors with high doses of radiation thanks to state-of-the-art patient immobilization and radiation delivery techniques along with high-tech quality assurance methods.

Kozak soon will use advanced methods to treat tumors with high doses of radiation thanks to state-of-the-art patient immobilization and radiation delivery techniques along with high-tech quality assurance methods.

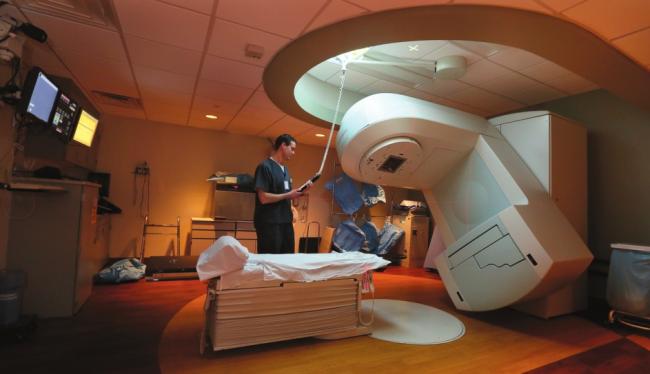

Stereotactic treatment uses the standard radiation therapy equipment—a linear accelerator—but with add-on equipment to be able to closely localize a tumor.

Instead of treating a tumor with a few beams of radiation, generally seven or more beams are used, Kozak said.

“You do it very, very, very focally … and so you deliver very high doses of radiation just to the tumor,” he said.

Mercy uses a new BodyFIX system, which allows a patient to lie on the table within 3 millimeters of the same spot each time. A gentle vacuum is applied over the patient after lining him or her up on the table in the exact position each time, confirmed through scans before treatment.

CT scans are used to track a patient’s respiratory movements over time to take small movements into account while targeting a tumor in the lungs.

Higher doses of radiation can be used because as the treatment becomes more focal, smaller volumes of normal tissue are treated, therefore lowering the risk of toxicity, Kozak said.

Gray is the unit of measure for radiation doses, and older treatments used 2 gray during each of 25 or more treatments. Stereotactic therapy generally uses 10 gray or more each time, but far fewer treatments are needed, Kozak said.

There are clear indications when this is a superior treatment, he said. It is most commonly used for early-stage lung cancers and certain forms of metastases to the lung, liver and spine, though it can be used on all types of cancers, he said.

“It’s sort of the modern-day equivalent of noninvasive surgery,” he said.

In early-stage lung cancer, where the tradition was to cut out the tumor, stereotactic radiation therapy is an appropriate treatment, he said.

Treatments are most commonly done five times compared to traditional treatments that required 30 to 40 radiation sessions.

For early-stage lung cancer, the cancer control rates also jump from 60 percent using traditional methods to more than 90 percent with stereotactic radiation therapy, he said.

“Much of the high-tech therapies are not so much technology driven or even physician driven, but they are high-quality physics driven,” he said. “And that’s someone (medical physicist) patients never meet, and we have an exceptional, new, energetic Ph.D physicist (Qing Liang) here to permit the safe delivery of these techniques.”

The physicist has to make sure the machine has been calibrated properly, the dose selected is actually delivered and distributed properly, the patient immobilization is appropriate and management of the patient’s motion is accurate, he said.

“We want to … have available to patients all potential radiation therapies that can benefit them and apply them in the most appropriate way,” he said.

Kozak, who started at Mercy last year, earned his medical degree from Vanderbilt University and served his residency at Harvard in Boston.

Soon after he started at Mercy, he began hosting a free monthly discussion group about various cancer topics for anyone interested.

Clinical trials

Another change this year will allow Mercy patients to begin clinical trials in more rare types of cancer.

Mercy has about 20 trials open, and they have focused on the most common types: breast, lung, colon and prostate. Over the past decade, Mercy has had 104 patients participate in trials, and of those, about 75 are still receiving treatment or followup care.

“Clinical trials are very specific what they’re looking for,” registered nurse Jan Johnson said. “Eligibility for the patient is very tight.”

Last

year, Mercy screened more than 700 patients and found only 24 were

eligible, and 15 went on a clinical trial, said Rhonda Graf, compliance

coordinator at the cancer center.

Donna

Conkle of Whitewater is one patient who entered a clinical trial as

part of her treatment for breast cancer. After going in for a routine

mammogram in spring 2013, she needed a biopsy, which then showed she

needed surgery.

“I

went through that, and they talked to me about if I wanted to do a

clinical trial,” she said. “I didn’t have to do it, but I did it because

I thought it could help with the studying (for) the future.”

The

clinical trial meant she received radiation along with chemotherapy.

The standard treatment would have been just the radiation, but the chemo

was added for the trial, she said. Only time will tell what the entire

trial will find, but Conkle said she felt like she could help by being a

part of it.

Mercy

offers Phase III trials, which test whether a new treatment is more

effective than the standard treatment. Patients in clinical trials at

Mercy always receive the standard of care, Johnson said.

People are sometimes misinformed about trials, thinking they’ll get a placebo, she said.

Instead,

patients receive the standard treatment, in addition to the trial

treatment, which can be additional medications, she said.

When

new clinical trials become available, Mercy staff looks at the details

to see if they have enough patients to warrant opening a trial, Graf

said.

This year, the

medical oncology department transferred over to the National Cancer

Institute’s independent model, which allows Mercy to open clinical

trials quicker to meet the needs of patients.

“Now, we’ll be able to look at some rare ones and trials we haven’t offered before,” she said.

Palliative care

“When

we think of innovation, we think of new machines and new drugs,” Kozak

said. “We don’t necessarily think more holistically, and true innovation

happens when we have improvement.”

Kozak jokes with his patients that he wants a palliative care physician for himself.

Palliative

care, which stresses quality of life, has grown and is important

because it involves a separate physician from the treating physician, he

said.

Palliative care

is specialized for people with serious, chronic illnesses and focuses

on providing patients with relief from symptoms, pain and stress, said Dr. Kelly Fehrenbacher, who is board certified in internal medicine, geriatrics and hospice/palliative medicine.

Various

studies have routinely shown palliative care improves overall patient

care, she said. A recent study found patients with advanced lung cancer

lived longer with early palliative care intervention compared to those

with palliative care involvement later in their illnesses, she said.

The

goal is to improve the quality of life for the patient and his or her

family through a team of doctors, nurses and specialists, she said.

Mercy

has had an inpatient palliative care consultative service since 2009,

and Fehrenbacher now offers consultations in the Mercy Outpatient

Palliative Care Clinic in the Mercy Health Mall, as well as home visits

for home-bound patients.

Fehrenbacher

said she asks patients what is most important to them and what they

want to focus on in their remaining time. Some patients choose to try

any available treatment, while others wish to forego further

curative-type treatments and focus on the quality of time left and not

just quantity, she said.

“I

try to provide an extra layer of support for patients and families and

help them navigate the difficult medical decisions they are facing

regarding future care and goals of treatment, as well as discussing

advance directives when needed,” she said.