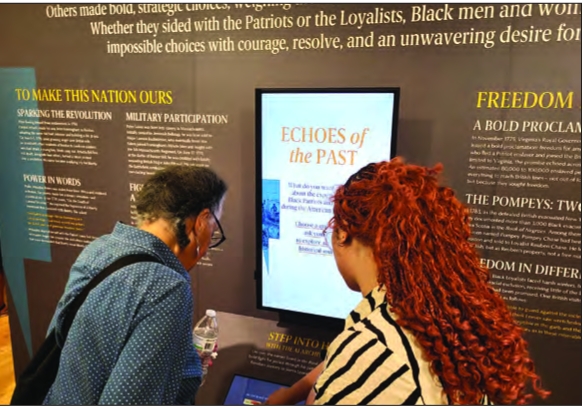

Angela Tate, chief curator and director of collection at MAAH, shows visitors how to use the exhibit’s interactive digital technology.

From

left: Kate Fox, executive director of the Massachusetts Office of

Travel & Tourism; Dr. Noelle Trent, president of MAAH; and chief

curator Angela Tate unveil the new exhibit together.

New MAAH exhibition centers Black history of Revolutionary War

Visitors gathered at the Museum of African American History (MAAH) in Boston last Monday to see the unveiling of their newest exhibit titled “Black Voices of the Revolution.” It reexamines the diverse stories of African Americans during the Revolutionary War era to challenge traditional narratives by highlighting the individuals who have often been left out of mainstream historical accounts.

Black Voices of the Revolution explores the American Revolutionary period by centering Black and female perspectives. The exhibit is organized into six sections, including “Freedom for Whom?” and “Mapping Black Revolutionary Boston,” while featuring notable historical figures like Crispus Attucks, Phillis Wheatley Peters and Prince Hall, among others. Created through a partnership with TimeLooper, it incorporates interactive digital technology powered

with AI that uses the museum’s collection of primary sources to

generate answers to visitors’ questions about the people and history.

The exhibit also displays some archeological artifacts found from their

Nantucket location, accompanied with 3D printed model replicas that

guests can physically interact with.

Dr.

Noelle Trent, president and CEO of MAAH, explained how this exhibit is a

new style for the museum to show people a different perspective on the

history of the American Revolution and the ideas people traditionally

don’t know about.

“It

allows us to show people what the Black community was thinking because

we’re not a monolith and we’ve never been a monolith,” she said. “There

are so many different powerful stories, especially the stories of women.

Black women’s voices have historically been minimized in the public

narrative, so we have worked really hard to present some new ideas.”

By

shifting the focus of the American Revolution through the Black lens,

the exhibition adds a crucial narrative that redefines the understanding

of key moments from the period, putting a spotlight on stories from

individuals often overlooked that shaped the country’s founding.

The

creation of Black Voices of the Revolution was more challenging than

some of the museum’s previous exhibits. Angela Tate, chief curator and

director of collection for MAAH, described how the Black community

during the period didn’t leave an extensive amount of personal written

records. Much of their presence is mainly seen in historical archives

from petitions documenting their fight for freedom, confessions and

newspapers.

“Using

these digitally immersive technologies, we get to bring these documents

to life that visitors can engage with on their own terms and think

about, what it means for us to have to do this excavation of the

archives to tell these stories,” said Tate.

Visitors

described the exhibit as a powerful way to connect with history by

sharing and engaging with the diverse experiences that the Black

community faced at the time as well as similar experiences faced today.

“I

think people aren’t able to accept what they can’t understand, and art

helps bridge that gap by making things accessible and easier to

understand,” said Nyla Cross, a Harvard Du Bois intern curating an

exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts. “Exhibits like this and art take

really traditional, intense, and complex topics and simplify them,

putting them in an avenue that’s easier for people to understand, easier

for them to empathize with and more engaging.”

Trevon

Henderson, also a Harvard Du Bois intern, described that it is an

immersive space for people to engage and participate in. “Having a space

like this to be able to teach is definitely important because it

doesn’t allow anyone to be stagnant. You get to walk around, and you get

to interact, that’s significant for anybody seeking to learn. Neil

deGrasse Tyson always says, ‘You want your work to be meaningful, you

want the space for the viewer to be meaningful, and you want them to

pose questions and ask questions about things.’”

As

Tom O’Reilly, a member of the museum, explained, the importance of art

was a way to help people understand different voices. “In many ways we

have a shared history, the same dates, the same times, but different

experiences. A big part for me is, I think the solution is in the other

person’s space. Whatever the problem

is, the solution’s in the other person’s place. The more you understand

where the other person’s coming from, the more we’re able to figure out

what the solution is to the problems we face together.”

The

exhibit was funded by a grant from MA250 administered by the

Massachusetts Office of Travel & Tourism. This funding was crucial

for MAAH to be able to create this exhibit. “We’re very grateful to the

state of Massachusetts for offering this funding opportunity because,

without it, we wouldn’t have this exhibition at all,” said Tate.

Especially

after the museum lost its IMLS grant funding due to federal cuts, it

has been increasingly more difficult for them to not only create new

exhibits, but have educational events to go along with it as well.

“Not

having that [grant] meant that we had to rethink how we were going to

do the educational program, particularly around this exhibition,” said

Trent. “The programming is now delayed, and with the injunction, we’re

able to rethink some things. But we’re hoping that people see this and

they want to support this effort, and that we can encourage school

groups to visit and engage with the digital technology as well.”

Places

like the Museum of African American History are essential for educating

people about the experiences and contributions of African Americans

during the founding of the United States. “I think the work around is

leaning on community partners, donors to the museum, and other

institutions with similar missions who want to partner with us. At this

point in time, I’m really leaning on the community,” Tate said.

Without sustained funding, continuing to uncover the history and importance of these stories becomes harder to preserve.

Federal

funding cuts to museums are catastrophic, particularly for ones like

MAAH that aim to teach and expand the understanding of America’s full

history.

“For federal

funding to be cut for spaces like these, it means that there is

definitely a revolt on learning and teaching. Thankfully we’re able to

still have spaces like these and people who won’t just stand for

injustice,” said Henderson.

With

the Trump administration’s increasing pushback on cultural

institutions, it creates a dangerous standard on how history can be

portrayed and discussed in the country.

“It’s

tragic that we have a governmental moment where the ambition is to

reduce us, to make everything smaller and one voice, that cannot be the

story of a great nation. A great nation has never been only one voice or

one story, and it cannot be. What makes the greatness of America is the

elaborate, composite make up of it,” said Edmund Barry Gaither,

director and curator of the Museum of the National Center of

Afro-American Artists.

“All

of the people who have brought pieces of themselves, their legacies and

heritages from every spot in the globe, have woven them into a

magnificent tapestry. And now we have someone in charge of the tapestry

who wants to cut it up and rip out all of the threads that are not his

own.”

Like the pieces

that African Americans contributed to the founding of the United States

during the American Revolution, the diverse stories and backgrounds

different people bring are essential to understanding the shared history

all of us have.

“Every

institution like this one has its purpose of making people larger and

more fully engaged with what it means to be human. What it means to be

human, is to be open to a larger world,” Gaither said.

For

MAAH, they continue to strive to protect the history which shaped the

United States, a country that was built upon by those who were denied

freedom but shaped the very foundation of this nation.

“I

hope people realize that African Americans have been here in this

country, that they’ve made significant contributions. We hope to round

out some stories that people think they know,” said Trent.