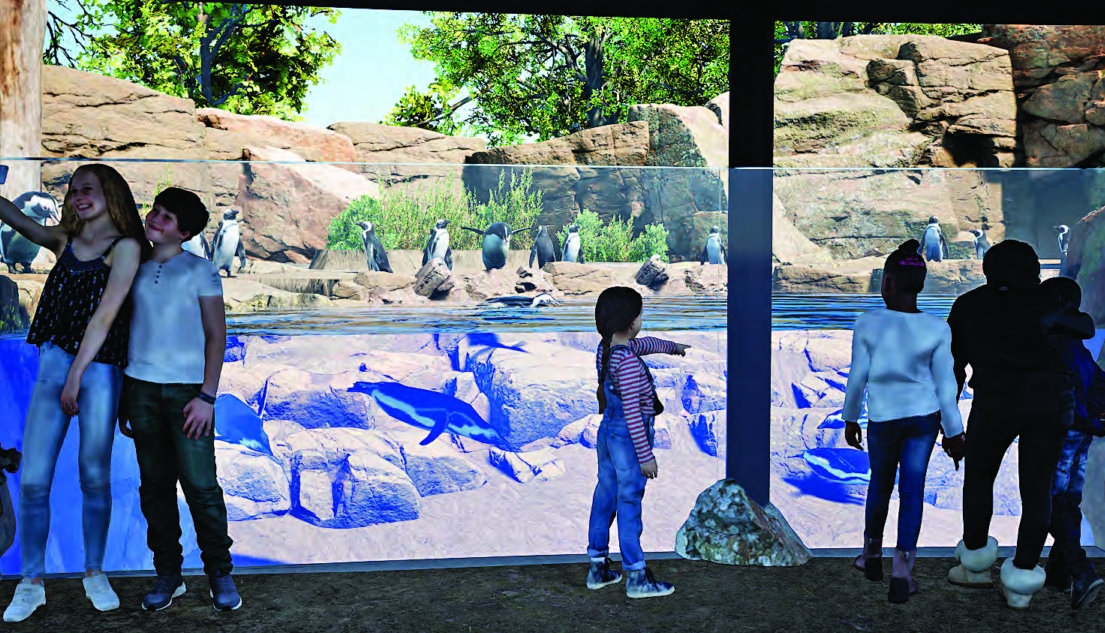

Geothermal system in the works: A rendering shows an under-construction habitat for African penguins at the Franklin Park Zoo, slated to be opened in spring 2026. The habitat will be heated and cooled using a geothermal system to increase energy efficiency.

A

geothermal energy plant near the Salton Sea, California. Water pipes

are shown in the foreground and steam exhaust in the background.

The Bay State Banner wants to hear your questions about the climate and environment. This article was produced as part of a new project called Encyclopedia Climatica, in response to a readersubmitted question. Do you have a question about climate or environment? Submit it to us at tinyurl.com/banner-climate-questions or email to [email protected].

A READER ASKS: “Can you explain how geothermal energy works and how it can be applied to housing? Is it ‘clean’ energy?”

A rookery of new residents will be moving into Franklin Park Zoo next year. When that colony of African penguins arrives next spring, the exhibit that will house the temperate birds will be heated and cooled by the heat of the earth.

The system will use 20 boreholes — vertical pipes, installed 600 feet into the ground — to pump a heat-transferring liquid through a geothermal system to regulate the temperature of the water and the air inside the new building.

It doesn’t come cheap — the system costs an estimated $800,000 to $1 million more than a traditional setup, said John Linehan, president and CEO of Zoo New England.

But it will operate more efficiently, meaning a reduction in carbon emissions, a priority for Zoo New England, which runs Franklin Park Zoo.

“Being a conservation organization means setting good examples and using technology where we can, to reduce our carbon footprint,” Linehan said.

Geothermal

systems aren’t just for the birds. Increasingly, across the region,

geothermal is being used to heat and cool homes, a solution that

advocates, officials and researchers celebrate as an important step

toward decarbonizing Massachusetts.

“It’s

a sustainable, reliable resource that we have, and we have it beneath

our feet,” said Melissa Lavinson, executive director of the state’s

Office of Energy Transformation.

Broadly,

with geothermal, there are different ways the earth’s heat can be used,

including for heating and cooling and for generating electricity.

Geothermal for heating and cooling

In

New England, the most prominent — and currently only — use of

geothermal is for heating and cooling buildings, like the pending

penguin enclosure.

The

systems rely on the constant temperatures found at shallow underground

depths. There, temperatures tend to hover at a consistent level, locally

about 55 degrees, which allows geothermal heat pumps to pull heat up

into buildings in cold weather or tuck heat underground when it gets hot

out.

In hot weather,

those systems pump a “geothermal fluid” — generally a refrigerant like

in an air conditioner — to pick up heat from a hot room. The fluid is

then carried underground to let the heat dissipate. In cold weather, the

reverse occurs. In both cases the physics of compressing and expanding

gases is used to amplify the transfer.

“All

you’re doing is using that constant temperature underground to act as

either a heat source or a heat sink, meaning it’ll either take the heat

out of a cooling fluid or add heat to that fluid,” said Emily Ryan, a

professor of mechanical engineering at Boston University and an

associate director at the school’s Institute for Global Sustainability.

Unlike geothermal for power generation, heat pumps are an appliance, not a source of energy.

“If

people start to hear the publicity around this networked geothermal,

and they’re like, ‘Great, we’re going to get geothermal energy,’ but

you’re not,” Ryan said. “You still need electricity from our grid to

power these systems.”

For

supporters, the benefits of a geothermal system are plentiful. The

systems tend to be more efficient than traditional HVAC systems.

“From

a decarbonization perspective, it can actually help reduce peak

electric demand,” Lavinson said. Geothermal heating and cooling systems

are up to 65% more efficient than traditional HVAC systems, according to

the U.S. Department of Energy

And

in a region like New England, with old housing stock built for cooler

temperatures, it can add a cooling system to buildings that didn’t

previously have air conditioning.

Supporters

also see a lot of potential in the ability to make the transition. Much

of the labor needed for laying out the pipes needed to transmit heat

underground is carry-over from gas systems.

“Digging,

putting in pipe, connecting pipe to homes and businesses, that’s stuff

that we do every day,” said Liam Needham, Eversource’s director of

customer thermal solutions.

Already,

there’s been proof-ofconcept of that transition at an Eversource

geothermal project in Framingham, said Zeyneb Magavi, executive director

at the Home Energy Efficiency Team, or HEET, a Boston-based nonprofit

focused on the thermal energy transition.

“The

gas pipe installer workforce, they literally went from installing gas

pipe one week to installing [geothermal] pipe the next, with a couple

hours of training,” said Magavi (HEET pitched the project to utilities

and has been involved in the process).

The

needed workforce doesn’t wholly exist yet. A key element of geothermal

HVAC systems are the boreholes — those vertical pipes, often a few

hundred feet deep, that reach constant temperatures. While some

companies exist to drill those boreholes, that segment of the workforce

needs to be expanded.

“Drilling

is obviously something that’s done for industry, for oil and gas

extraction, but I don’t know if we necessarily have the workforce in

place if everybody decided they wanted geothermal,” Ryan said.

And

the cost of installing the systems remains prohibitive. For a

single-family home, Magavi said that installation of a geothermal heat

pump can cost between $20,000 and $60,000. According to Angi’s List,

installation of a new boiler averages about $6,000.

“It’s kind of like if you had to install your gas boiler and pay for all your gas up front,” Magavi said.

One solution is linking a collection of homes or businesses to the same heating system, called networked geothermal.

That

bigger system, likely owned and operated by a utility, saves individual

customers the costs of installing geothermal heat pumps while bringing

the same benefits.

“It

shifts the financing model,” Magavi said. “It means that the utility

can do what a utility is for, which is large, upfront investment and

long-term payback for deliveries of a necessary human good.”

In recent years, the state has seen a handful of networked geothermal pilot programs announced.

In

2020, the state’s Department of Public Utilities approved Eversource’s

first-of-its-kind networked geothermal pilot program in Framingham,

serving 36 buildings and about 140 residential and commercial customers.

In

early 2024, National Grid announced a pilot program of its own at

Dorchester’s Franklin Field public housing development, in partnership

with the Boston Housing Authority. That project, planned to replace an

aging boiler, will serve 129 of the development’s 450 units. National

Grid didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Rate

systems to pay for networked geothermal have yet to be set in stone.

Needham said that it will have to happen before it can really take hold.

But Eversource is currently exploring one approach.

Residential

customers in its pilot pay $10 per month, plus their electricity bill

which covers the energy to pump fluid through the system, while

commercial customers pay $20 per month. Income-eligible residential

customers receive a discount rate of $8 monthly.

From

a utility perspective, use of geothermal, especially networked

geothermal, “sort of aligns in a couple of different areas,” Needham

said, pointing to the energy efficiency and decarbonization goals and

the easy workforce transition.

It’s

Framingham pilot kicked into gear late last year, Needham said, so it’s

gone through a cold season. Now the utility is watching to see how it

handles the summer. So far, he said, the system has operated as

expected.

But

networked geothermal isn’t a done deal. Another National Grid pilot

program, slated to be built in Lowell, broke ground in 2023 but was

cancelled in 2024, after the utility said it was no longer economically

viable.

Utility-owned

geothermal heating systems may offer other opportunities too. A pending

energy package at the State House would give the state’s gas utilities

the ability to construct big systems for individual customers.

Under a provision in Gov.

Maura

Healey’s Affordability, Independence, and Innovation Act, utilities

would be able to work with a single large customer, like a college or

hospital, to build a geothermal heating system.

Like

networked systems, the brunt of the cost would be shouldered by the

utility, letting the institution get the potentially cost-effective

efficiency of geothermal heating and cooling without the high upfront

cost, Lavinson said.

Utilities

would handle the construction and operation, and the customer would pay

back the cost through their utility bill over time. That solution might

help convince bigger customers to take on these systems, Ryan said.

And,

as clean energy efforts broadly are on the chopping block under the

administration of President Donald Trump, geothermal may have escaped

the worst of it.

While

tax credits included under the Biden-era Inflation Reduction Act around

many renewables were largely axed in the administration’s so-called

“Big Beautiful Bill,” sent to Trump’s desk July 3, commercial geothermal

tax credits survived (residential ones were less fortunate).

“It’s

actually one of the few topics that I like that still seems to be on

the federal radar,” Ryan said. “They are interested in geothermal,

where, at the same time, wind, solar, all those other ones are getting

cut.”

Magavi, who has

spoken with legislators about the technology, said she’s heard an

appreciation from Republicans about the non-intermittent nature of

geothermal — the earth isn’t cyclically going dark the way the sun does.

And the technology has a legacy of research and production in the

United States, she said, which might shift the politics around it.

“There is a kind of continuity of enthusiasm and support, even if there is a specific tax credit loss,” Magavi said.

Geothermal for power generation

The

less frequent application for geothermal — at least in the northeast —

is to generate electricity. Unlike the heating and cooling systems, a

longer pipe is used to get hot water from wells deep underground. As the

hot water is pumped to the surface, it becomes steam, which is used to

turn a turbine and generate electricity in much the same way that a coal

power plant uses the burning of coal to create steam.

The

system isn’t perfect — building it has some environmental impacts, and

the water has to be replaced to avoid causing sinkholes — but it can

offer cleaner, renewable energy.

Just not, for now, in New England.

That

kind of technology currently requires specific underground deposits of

hot water — or, per a developing technology, hot rock where water is

pumped down into the rock to be heated into steam. Geologically

speaking, this isn’t how this part of the country is constructed.

“The New England area does not have high-temperature anything underground,” Ryan said.

New

innovations have moved the technology toward potentially being able to

provide power generation in a wider array of locations, Magavi said.

Ryan

said that there’s been research into an ambient temperature system to

generate power, which would be less efficient, but could still be

effective. For now, that technology simply isn’t ready, but Lavinson

said that if it becomes available, it’s a solution the state would

consider implementing to reach its decarbonization goals.

“If

it turns out we do have the geology to do the deep geothermal that

power generation requires, I think that, yeah, we’re going to seize that

opportunity,” she said.