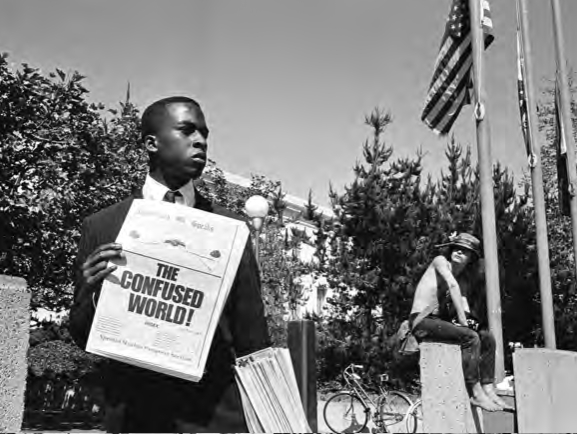

(top) Photographer Ernest Cole, from the film “Ernest Cole: Lost and Found.” (above and left) Ernest Cole photographs. Poignant documentary explores life and work of exiled South African apartheid photographer

In 1967 the world saw firsthand the horrors of Black life under apartheid South Africa in photojournalist and street photographer Ernest Cole’s, unflinching photobook, “House of Bondage.” Apartheid was legal systemic racial segregation in South Africa from 1948 to 1994. Apartheid spanned legal and economic segregation and social separation between European South Africans and non-white South Africans, favoring the former and discriminating against the latter.

“House of Bondage,” which

was first published in New York, was banned in South Africa for

depicting these harsh realities to outsiders. The country was already

impacted by UN-sanctioned boycotts a few years prior.

This

book ban subsequently forced Cole into exile in Europe and America for

the remainder of his life. His exile became a bondage of its own and he

often wrote, “I am homesick, and I cannot return.” Originally lauded by

his contemporaries for his work covering apartheid, Cole eventually

became homeless, faded into obscurity and died from pancreatic cancer at

49.

Haitian director

Raoul Peck’s (“I Am Not Your Negro”) latest documentary, “Ernest Cole:

Lost and Found” spotlights the South African photographer using his

photographs and his words with an emotional and visceral voiceover by

Lakeith Stanfield (“Get Out” and “Atlanta”). The short and slender

observer who stood at 5’4” was marked by feelings of otherness and

restlessness throughout his life. The moving and poignant film reveals

what happened to Cole between the release of his photobook and the

shocking discovery of his lost negatives and writings in a Swedish bank

50 years later. What follows is the story of a man who falls into

depression caused by the isolation of exile and the hopelessness that

occurs when the Western world promises freedom and fails.

Cole’s

mostly black-and-white film photographs cover an array of daily life,

from the dignified and the destitute to the happy and the hopeless.

Pictures of “nightmare rides” show train cars and platforms

designated for Black South Africans that are packed to the brim. Some

commuters grasp onto any bit of the train they can find as they hang off

the speeding locomotive, praying they don’t fall to their deaths. He

also photographs a white South African sitting on a bench labeled

“Europeans Only” and captures the monotonous life of Black South

Africans in the desolate, eerily quiet banishment camp of Frenchdale,

near the Botswana border.

Cole’s

work was inspired by French humanist photographer Henri

Cartier-Bresson’s “The People of Moscow.” These were photographs of

ordinary people doing ordinary things in ordinary environments. Cole

explains that this approach was the most effective way to depict the

realities of injustice and human rights violations in South Africa.

It is at times difficult to

decipher where Cole’s photographs are set. Is the image of a Black man

being brutalized by both Black and white police happening in Chicago or

Soweto?

Is the image

of a Black female nanny to wealthy white children who will learn to hate

her set in Pretoria or on Park Avenue? The images taken in the 1960s

and 1970s could also be taken today. This lack of distinction is the

point.

Chillingly,

Cole also reveals, “In the South I was more scared there than I ever was

in South Africa. In South Africa I was afraid of being arrested. In the

South when I was taking pictures, I was terribly frightened of being

shot.”

Two years after apartheid’s end, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was formed.

Established

in 1996 and chaired by South African Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu,

the commission allowed survivors of human rights abuses under apartheid

to share their experiences publicly. These abuses included simulated

drownings, electric shocks, sexual abuse, kidnapping and violence. It

also allowed violent perpetrators to give accounts of their actions and

request amnesty. The idea

for the commission was for people to acknowledge the truth while moving

forward with repair and restoration. The reconciliation was televised.

Peck

explains his choice to include this archival footage when he says, “I

knew that at some point, I needed to show the naked truth: barbarity,

abuse, torture.” He continues, “People forget it. They think apartheid

is just a figure of speech. No, people were dying. People lived their

whole life under constraints, like prisoners of their own country.”

While

Cole’s people were prisoners in their own country, he always felt like a

prisoner outside of his. His homecoming was bittersweet since he

returned posthumously. He died a week after Nelson Mandela’s release

from prison.

“Ernest Cole: Lost and Found” is now streaming on most platforms.

ON THE WEB

Learn more at magpictures.com/ernestcole