Mustafa

Farrakhan, Randy Muhammad and Ishmael Muhammad pray over the casket of

Minister Don Muhammad at the Morningstar Baptist Church.

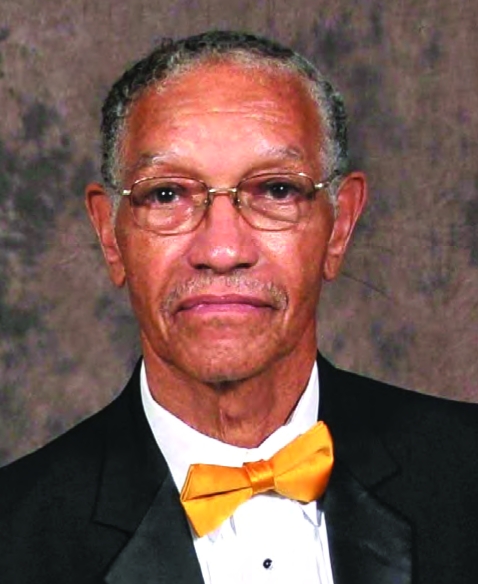

Minister Don Muhammad

Boston’s Black clergy members expressed shock and outrage after a 1992 incident at the Morningstar Baptist Church after a dozen young men barged into a funeral service for a rival gang member, fired gunshots and stabbed three people.

Minister Don Muhammad dispatched a detachment of the Fruit of Islam to the Blue Hill Avenue church, marching them from the Grove Hall location of Muhammad’s Mosque No. 11 to the Mattapan sanctuary.

The young men, many of them rescued from prison or life on the streets by Minister Don’s mission of redemption, stood straight and tall during the rescheduled funeral.

“They came in and protected us,” Rev. John Borders said, speaking during a memorial service for Muhammad at Morningstar on a snowy, wind-whipped day. “When I stood to preach, they were standing on each side.”

Muhammad died Dec. 17 at age 87. Borders, fellow clergy, Nation of Islam members and others recalled Muhammad as a leader to whom they turned for wise counsel and protection during the many decades he spent at the helm of the Roxbury mosque.

The protection he extended to Morningstar ruffled some feathers among brothers in the Nation of Islam and congregants at Morningstar. But Muhammad wasn’t interested in interdenominational conflicts.

“Minister Don realized this wasn’t about the Nation of Islam,” recalled his son, Don Straughter at the Dec. 20 service. “This wasn’t about the churches. This was about people helping each other.”

Muhammad was also remembered for his key role brokering peace between community factions, whether community activists, clergy, elected officials or gang members.

It was Muhammad’s work with gang-involved and incarcerated young men that first caught the attention of local law enforcement and led to a unique role of the Nation of Islam in the so-called “Boston Miracle” that attracted national attention in the 1990s for the 79% drop in gang violence.

But

that alliance was long in developing. Muhammad was outspoken in

criticizing police after Boston cops shot and killed unarmed Black men

in a string of shootings in the early 1980s. The election of Raymond L.

Flynn to Boston City Hall in 1983 brought new leadership to the city and

a new police commissioner, Francis M. “Mickey” Roache, who knew

Minister Don from his work in the Community Disorders Unit.

Despite

outside criticism, the alliance between the Nation of Islam and law

enforcement – which grew to include State Police, state prosecutors and

the U.S. Attorney’s Office – yielded results. Alongside the Boston Ten

Point Coalition of Christian clergy, Minister Don and his Nation of

Islam acolytes worked the projects, streets and schools to intervene in

gang disputes and maintain peace.

Embracing

the view expressed by Rev. Jeffrey Brown that “we’ll never arrest

ourselves out of this situation,” Minister Don led efforts to find

alternatives to gang life while interceding to resolve conflicts between

factions.

Nearly

unheard of in other cities, it was common in Boston to see Nation of

Islam members under Minister Don join with police brass like Area B

Commander William “Billy” Celester and the mayor at press conferences,

responding to outbreaks of violence or pushing for more state and

federal resources to address youth violence.

However,

Minister Don’s close relationship to civic powers did not prevent him

from speaking out over incidents like the police converging on the

Mission Hill projects to search for a non-existent Black suspect after

the murder of Carol Stuart by her husband Charles, whose lies set off a

brutal manhunt.

Muhammad

was also an ardent believer in economic self-sufficiency for African

Americans, promoting business development and investment in the Black

community.

The unusual

nature of Minister Don’s prominence in Boston civic life was apparent

in a 1990 appearance at Harvard University’s Institute of Politics,

where he addressed a packed auditorium during a fall seminar. Some

students came out of curiosity, some to question the Nation of Islam’s

fraught relationship with the Jewish community.

Muhammad’s

forthright presentation of the Nation’s peaceful philosophy, his

message of economic empowerment and rescuing young people from lives of

despair won him sustained applause at the end of the hour.

Born

Don Straughter in Beckley, West Virginia in 1937, he moved from the

heart of coal country to Boston at age 17 to work with his brother,

Justice, in dry cleaning. Shortly after arriving in Boston, Straughter

met his soonto-be wife, Shirley Upshaw, who came to Boston from Halifax,

Nova Scotia. They were married within a year of meeting each other.

The

couple joined the Nation of Islam as part of Mosque No. 11 on Intervale

Street, which was then headed by Louis X, a Roxbury native formerly

known as Eugene Walcott, who

later took the name Farrakhan. During Farrakhan’s leadership of the

Roxbury mosque, he and Muhammad forged a decades-long close

relationship.

When

Farrakhan sought in 1981 to revive the Nation of Islam after several

years during which the organization was dormant, he relied heavily on

Muhammad to build out the organization, recalled Mustafa Farrakhan, the

NOI leader’s son.

“He

was a hero in the Nation,” Farrakhan said during the service at

Morningstar. “He was one of the pillars my father depended on to rebuild

the nation.”

Over the

decades, Farrakhan tapped Muhammad to train ministers across the

country and, from time to time, to negotiate conflicts NOI mosques had

with local authorities. On one such occasion, Muhammad held negotiations

between New York’s Mosque No. 7 and then New York Police Commissioner

William Bratton, with whom Muhammad had worked in Boston when Bratton

was on the Boston Police Department command staff.

“This

was a great statesman, a diplomat,” said Minister Rodney Muhammad, who

now leads Mosque No. 11. “He was respected from the streets to the

suites.”

Muhammad is

survived by his five children — Yvette Muhammad, Cheryl Straughter, Don

Straughter Jr., Shirley Straughter Carrington and Brian Straughter — as

well as 20 grandchildren and 11 great-grandchildren.

Family members recalled Muhammad’s kindness and his love for his wife, Shirley, who passed away last year.

Brian Wright O’Connor contributed to this report.