(top

and above) The [Virtual] Art Gallery roundtable hosted by the Bay State

Banner and the Museum of Fine Arts on Feb. 29, drew a crowd to hear

Black artists speak about their work and lives.

Robert Freeman, “Connections”

Ekua Holmes, “Sufficient Grace, Ms. Ivy Beckles”

(from left) L’Merchie Frazier, Paul Goodnight, Rob Stull, Ekua Holmes, Shea Justice, James Perry, Robert Freeman, Ron Mitchell

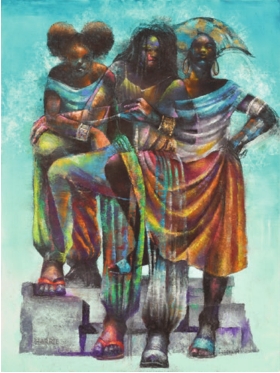

Paul Goodnight, “We Are Moses’ Children”

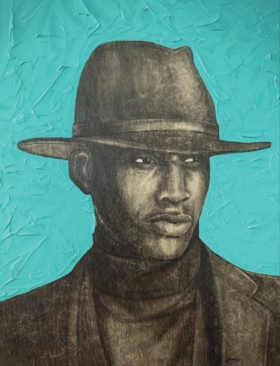

James Perry, “blackhatintiffanyskies”

Last Thursday evening, about 90 enthusiastic supporters of Black art gathered at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston’s William I. Koch Gallery to attend a [Virtual] Art Gallery roundtable, themed “The City Talks: Black Art in Colonial Spaces.”

The roundtable, presented

by the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Bay State Banner, featured six

of New England’s leading Black visual artists who have been spotlighted

in the Banner’s [Virtual] Art Gallery series: Robert Freeman, Ekua Holmes, Paul Goodnight, Shea Justice, James Perry and Robert Stull.

Ron Mitchell, editor and publisher of the Banner, and L’Merchie Frazier, mixed-media artist and executive director of Creative/ Strategic Planning for SPOKE Arts, moderated the Feb. 29 event.

“African

American art is the pure joy of our people,” said Mitchell in his

opening remarks. “It lifts us up. It keeps us going. It empowers us as a

people.” He thanked the featured artists for their creations.

Frazier asked the artists why Black artists are so underrepre sented in the Western art canon.

Freeman

spoke first. The figurative painter said that for a year back in the

early 1980s he found most Newbury Street art galleries unwelcoming

spaces for African Americans.

“My wife would drive the U-Haul van. I would take

these giant paintings out and into the galleries, and every single

gallery each time would say no,” said Freeman. “So I took the show to an

alternate gallery called the Chapel Gallery in Newton.”

When the Chapel Gallery exhibited Freeman’s “Black Tie” — a painting intended to

represent the discomfort we all might feel coming into circumstances

that are rather new to us — the arts editor for the Globe Magazine saw

it and placed it on the front page of the arts review. The next day,

every gallery on Newbury Street asked to exhibit Freeman’s art. But he

said no.

The Chapel

Gallery sold “Black Tie” to the Newell and Kate Flather family. The

Flathers donated it to the Museum of Fine Arts, and the museum recently

loaned the painting to Governor Maura Healey to hang in the State House,

said Freeman.

“It was

really the alternative gallery that made the difference,” he said. “I

would press all young artists to do what I did. Certainly, go to the

galleries you want to represent you, but also go to the alternative

galleries.”

Holmes, a

mixed-media collage artist, said, “In 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. was

assassinated, and the streets of Boston lit up. 1968 was also the

beginning of the Black arts mural movement here in

Boston. So, you had Gary Rickson and Dana Chandler not asking for

walls, but claiming walls, to express the voice of the people, which was

not being heard downtown. That was a revolutionary act.”

The murals Rickson and Chandler painted inspired her and other young Black people to become artists.

“It

left a deep impression on many young minds,” Holmes said. “I think Paul

[Goodnight], myself and other artists who I’ve heard, have said, ‘I saw

those murals and I knew I wanted to be an artist.’ So, art does have a

tremendous impact on young people. It is incredibly powerful.”

Holmes said she’s grateful that her third-grade teacher said to her mother, “Hey, I think your daughter could be an artist.”

“[Our

parents] wanted doctors, lawyers — even secretaries and nurses — but

not artists,” Holmes said. “Weren’t [artists] all crazy? Would they ever

leave home? Would they ever make money?”

Goodnight said he started drawing and painting as a way of communicating.

“I

came back from Vietnam and had a major speech impediment. I saw this

mural that Gary Rickson did. It’s called ‘Africa is the Beginning,’”

said Goodnight. “Coming back from Vietnam, I then turned to heroin

because I had to cope. I would stand and look at that mural for hours,

because that was what I wanted to do.”

He continued, “There was a group of folks we called the Black Artists Union. Napoleon Jones-Henderson came to us

and said, we are going to go to the National Conference of Artists.

Napoleon introduced us to a group of artists who I had never seen

before. I never knew the power of artwork, the image.”

Muralist John Biggers mentored him, Goodnight said. “He would say things that solidly made me feel as though what I

was doing was valuable. He would say, ‘Your job is what you get paid

for, but your calling is what you’re made for.’ That sealed it.”

Goodnight attributed having “many more good days than I’ve had bad” to art.

Frazier also asked the artists, “What does it mean to have your art in these traditional spaces?”

Times have really changed, Freeman replied. “Fast enough? No,” he added, “but they have changed, and they are changing.”

“I

see that there are efforts of repair,” said Holmes. “I had a show here

[at the MFA]. As a little girl who used to come to Saturday classes here

with my mom, I never dreamt that [would occur].”

“I

feel good about having my art anywhere,” said Goodnight. “We need to

have more people who have been advocates of art so we can keep this

thing going, and I really would love to see an institution for visual

artists in Roxbury, Dorchester or Mattapan.”