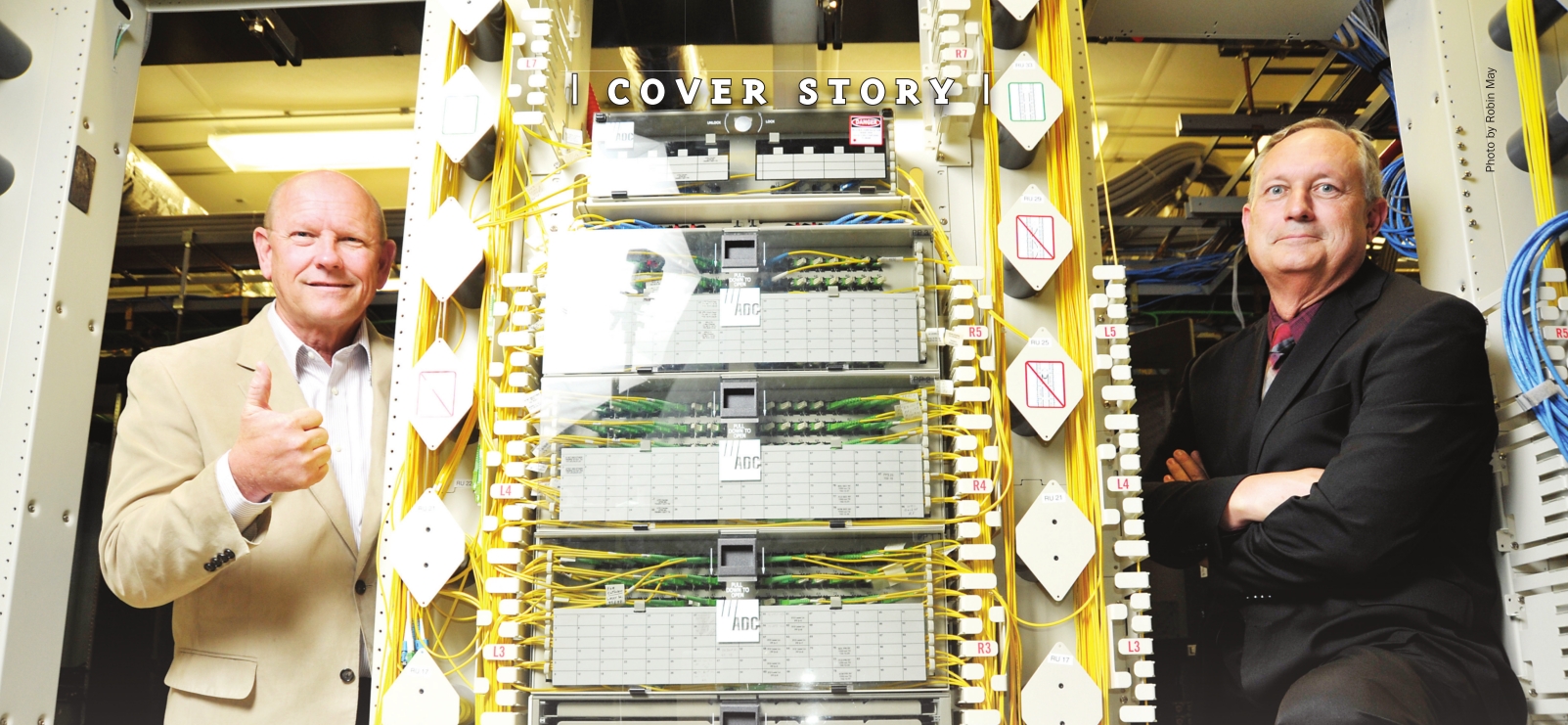

More than a decade ago, Joey Durel and Terry Huval set off on a risky trek — bringing fiber tele-com to Lafayette.

The city embraced the journey and has been on a promising trajectory since.

More

than 100 years ago, conventional wisdom was that building a utility

system in a one-horse town like Lafayette wasn’t a good idea. The big

corporations that provided electricity decided that it wouldn’t pay them

enough to bring light to the city, and so they told Lafayette’s people

they would just have to wait. They were in charge, they had the money

and they wanted Lafayette to be a good little city and grow on their

schedule, not hers.

But

the people who built Lafayette weren’t really into waiting, or

conventional wisdom, or doing what they’re told, and so they made what

was predicted to be a huge mistake: They sold bonds and built their own

damn utility system. Now the descendants of those people have the

largest municipally owned utility system in the state, and they enjoy

the most reliable electricity at the best price in Louisiana. That

system also regularly dumps cash into the city’s coffers, which is in

turn used to support infrastructure and government functions.

LUS

is one of Lafayette’s most prized and beneficial assets, all because

the people of this city suffer from a unique kind of audacity, the kind

of audacity that has marked the development of many of Lafayette’s most

successful efforts — an upstart international music festival, an ice

hockey team in a steamy Louisiana town and a government-owned fiber

telecommunications network.

This

month marks the 10th anniversary of the public vote that authorized the

sale of bonds to build LUS Fiber. It’s only been six years — mostly

because of delay tactics by more of those big corporations — since the

system started offering service to residents (and five since it was

offered to businesses),

but

already LUS Fiber is going to operate in the black this year — even if

you include the inflated depreciation percentages applied to telecom

systems. If you look only at operating costs, bond payments and

revenues, the fiber system has been cash positive since 2012.

LUS

Fiber brings the “fastest Internet in the world” to Lafayette, with

residential gig service equaled only in Tokyo, Seoul, Singapore,

Chattanooga and Kansas City. Our fiber system has attracted high tech

industry to Lafayette, creating more than a thousand jobs (so far). The

mere existence of this system has forced other utility providers in our

area to upgrade their systems ahead of their schedule and keep their

prices low — not to mention making Cox a better company for locals to

deal with. LUS Fiber revenues are projected to reach $50 million

annually in the next nine years.

By

any measure, it is a success — just six years in, a success. And those

who said (disingenuously, at best) that it would fail were wrong. Wrong.

There's

a reason that, even today, Lafayette is one of only a handful of

American cities with a municipally owned fiber system. Even here, in a

city with 100 years of utility experience and that pesky audacity, a

very specific set of circumstances had to exist, and a very specific set

of people had to get involved, for it to happen.

City-Parish

President Joey Durel describes it as planets aligning. There were so

many spokes to the wheel, and if just one had not been in place, he’s

not sure we’d be marking the anniversary of anything this month.

“I guess the good news was, I didn’t know what I couldn’t do at the time,” Durel says.

Among

those planets were Durel and Terry Huval, LUS’s longtime director and a

highly respected person in the utility world. Also required were a

supportive City-Parish Council made up of men with a bent toward

progressive thinking, something that was lacking before they arrived.

And the last piece was a group of community activists and creative

types who were, perhaps, the most audacious of all.

For

Durel, a Republican business owner who ran for public office with the

(laughable?) goal of making Lafayette a better place, the story really

begins in November 2003, right after he was elected city-parish

president for the first time. He’d worked with a transition team to

decide which department directors would stay, and he was making the

rounds to break the news.

Huval was definitely a keeper. During that first meeting, Huval said, “I want to show you something.”

He pulled out a binder of information he had picked up over the years, about the idea of fiber to the home.

Durel,

coming from a small business, Chamber of Commerce background, had a

predictable reaction: “Why would we compete with the private sector?”

Huval had the answer, and by the time Durel left Huval that day, he was

saying something else.

“I

said, ‘Shame on us if we don’t continue to look at this. Shame on us if

we don’t try until we get to a brick wall we can’t pass,’” Durel

recalls.

Two entities

tried their best to be that brick wall: Cox Communications and Bell-

South, later AT&T, telecommunications companies that a) didn’t want

competition in Lafayette and b) didn’t want this cancer of municipally

owned utilities getting out of hand. Durel’s wife Lynne “is much smarter

politically than I am” and asked him flat-out why on earth he wanted to

fight billion-dollar corporations to do this.

The

answer was simple. “I was tired of watching politicians allow

out-migration from our state. I had heard a lot of talk, but nobody ever

did anything about it,” Durel says. He wanted to find that one thing

that could change Lafayette for the better: “I thought this was our

opportunity.”

He had to look at the risk to the city’s existing assets first.

“With

fiber, I felt early on that this was really low-risk,” Durel continues.

“Despite the rhetoric of the opponents and the dollar amount, I felt

that if we spent all the money and we couldn’t get any customers, the

cost to the citizens would be minimal, but the possible payback was so

good. The political risk, honestly, I never cared about it.”

In fact, two people Durel really respects came to his office to tell him that maybe fiber should be a “second-term issue.”

“I

told them, thanks for caring about me, but I swore I’d never have this

conversation, about something that’s the right thing to do but I won’t

do it because it’s political suicide,” Durel recalls. “I told them that

if I got thrown out of office for trying to do the right thing, I’m OK

with that. I have a great wife and a great life, and I’m OK with going

back to that.”

He also believed that politicians who work like they will only have one term are the ones who get rewarded with a second one.

“If you do the right thing for the right reasons, people will respect you,” Durel says.

And they did, and returned him to office twice.

Terry

Huval is one of those audacious Cajuns, a man who has voice mail

greetings in French (first) and English (last), and who is known for his

devotion to classic swing, Cajun music and his red beret. He’s the

reason callers to the LUS automated system hear folklorist Amanda

LaFleur’s perky “Bonjour!” instead of some canned, impersonal cut-rate

Siri.

Huval’s fiber story starts a long time ago.

“A

few years after I came to LUS in 1994, we decided to highlight our

100th year since the 1896 vote to establish the electric and water

system. I was always intrigued as to what led the citizens in Lafayette

to vote for that initiative, and later learned that it was simply a

strong desire of the citizens to move their community forward,” he

remembers.

Communities

have always needed “highways of commerce” to grow, Huval says, be it

waterways, railroads, electricity or interstate highways. For him, it

was clear that broadband was the highway of the future.

“The

vision was simple: Lafayette was already benefiting from a very

successful electric, water and wastewater system, and LUS could leverage

its expertise to offer Internet and other telecommunications services,

if that is what our community wanted,” he says. “After we threw out the

idea, the entrepreneurial, wildcatter spirit of Lafayette seemed to take

it from there.”

That

spirit had some help in the form of critical political mistakes by the

incumbent providers. Durel remembers that the president of BellSouth

came to a Rotary Club meeting here and basically said that Lafayette was

getting above itself, adding that “New Orleans doesn’t even have this.”

“That

was the wrong thing to say to this community,” Durel says. “If we can

be first, that is something this community will wear with a sense of

pride. It’s that risk-taking mentality, coupled with the culture of

working hard and playing hard, all working together.”

But

even with all that spirit, one thing this community did not have was a

long, strong history of coalition-building, of activism. That’s where

that audacious group of citizens came in, to build an army that would

fight for an amazing idea.

“It’s

a pretty big deal, what we accomplished,” says community activist John

St. Julien. “Community organizing is something that Lafayette has been

deficient in. The Horse Farm fed directly off the fiber fight. Other

than those two issues, there’s not been much in the way of civic

activism here.”

But

that is what happened. St. Julien and his wife, Layne, Stephen Handwerk,

Mike Stagg, André Comeaux, Gobb Williams, Don Bertrand, Bill

Fenstermaker, Kaliste Saloom III and dozens more banded together in a

motley crew of old, young, establishment, non-establishment, black,

white, Democrat, Republican, you name it. That citizen group created and

ran the campaign for that July 2005 election.

There’s

a picture of that group on election night, standing in the street,

holding signs, fists raised; it’s a perfect capture of that spirit, says

Gobb Williams.

“We

were waiting for the results ... I think we were at the Cajundome;

wherever we were, as a group we started looking at each other. We all

had the same thing in our hearts, that we did not belong there. And we

passed the word around, let’s get out of here,” recalls Williams. “I

said we can go to my office, and so we came to the parking lot at my

office and celebrated the victory. Republicans, Democrats, independents,

black, white, Spanish, French, all working together for one cause. I

always get chills when I look at the picture, because I realize that we

had this group of people, a core of people, working for one cause,

uniting our resources, and we were victorious.”

Handwerk,

now director of the state Democratic Party, had recently moved to

Lafayette to run a web development business. He had a Cox modem for

downloading but had to use dial-up to send anything.

AT&T had terrible service, he says. Then he heard about fiber, and met with Huval.

“It

all made so much sense. But with the conservative leadership of this

community, I felt there was no way the Republicans would sign on,”

Handwerk says. “Then I heard the LUS story.”

A community that had taken that kind of step in the 19th century might actually accomplish this, he thought.

But

it wasn’t easy. “It seemed like one obstacle after the next,” Handwerk

recalls. “We were a bunch of community activists, and there were these

huge companies against us. It really was a David vs. Goliath situation.”

That was exactly the reason Gobb Williams got involved.

“No.

1, what really sold me on it, was that these people in our government

were willing to stand up against corporate America to provide us with an

alternative,” Williams says. “And, I had never seen such a diverse

group of people ready to fight for and believe in the same things I

believed in.”

One of the biggest problems, everyone agrees, was explaining to people just what the heck fiber meant.

“Cox

and AT&T were spending a huge amount of money to distort the

conversation, and what was worse, the biggest obstacle — nobody knew

what we were talking about. We would send out a mailer saying ‘Vote for

Fiber,’ and they thought we were talking about bran flakes,” Handwerk

says.

“We wondered how

much this idea had resonance with a whole lot of people whose hobbies,

jobs, interests didn’t run that way [to technology],” recalls Layne St.

Julien.

But the larger idea did. She remembers in particular a “wonderful” man who lived on Eighth Street.

“He

called to ask for a yard sign, and I went over there. He must have been

75, 80 years old, and lived in a very old house,” she says. “I asked

him why he felt so strongly about this issue. And for him, it was kind

of a patriotic thing. He felt like it was a good thing for the future

and for kids. He pointed to the children playing up the street and said,

“All of these kids can use that.”

“For certain of us,” she says, “that was a defining moment.”

The group tailored its message to each market. Knocked on doors — so many doors.

“We

wrote phone scripts. We worked the phone bank,” Handwerk recalls, with

Republicans and Democrats working side by side. “It was really surreal,”

he says, “but it was empowering as well.”

That’s one of the planets aligning that Durel mentions.

“I’m

proud of the parish executive committees of those two parties holding

their noses but speaking in unison,” Durel says. “They really did unite

the people.”

“I’m

proud of the parish executive committees of those two parties holding

their noses but speaking in unison,” Durel says. “They really did unite

the people.”

Williams says that unity is still “a memory I cherish.”

“I

will remember that as long as I live, and I say this with a full heart,

the people I worked with on that campaign, they will forever have a

special place in my heart,” Williams says. “Erin [May] made a little

card during the campaign, a small card with everyone’s name and phone

number on it. I still carry that card today in my wallet. I will never

get rid of this card.”

Aside

from the truly grass roots nature of the citizens’ campaign, two other

items played a big role in the success of it. First, the city

administration started using another Lafayette anomaly, another one of

those upstart, ridiculous, unique Lafayette assets — Acadiana Open

Channel. The weekly

program hosted by city officials offered plain-spoken information, and again — unbelievably — it worked.

“That

helped us evolve to the next level, going to a vote, mobilizing

people,” Handwerk recalls. Secondly, the “big boys,” Cox Communications

and AT&T [nee BellSouth] started dumping money into a campaign that

can only be described as ham-fisted.

“They

did ads with people who purported to be from Lafayette, but they had

fake Louisiana accents. Just terrible accents, and white trucks with

Texas plates,” John St. Julien recalls. “They did all of this stuff that

was so dumb.”

For

instance, there was the push poll, John St. Julien remembers. “It was

about 45 minutes long, and full of the most outrageous questions.” One

started with information about the LUS lawn-watering schedule, which the

pollster referred to as “rationing.” Then the pollster asked how you

would feel if your Internet was rationed so your neighbor could download

pornography.

The

fiber group would pull out each lie or distortion, break down all the

false information and send it out in email blasts to show just how

ruthless the big boys were going to be. And it turned out to be

invaluable to the pro-fiber side. “There’s no better way to educate the

community than controversy,” Durel says. “I hate taking the brunt of it,

but I learned through this process, if you want something done and the

public needs educating about it, you have to have controversy.”

There was a lot of money spent, and not just to stop Lafayette. It was to make an example out of Lafayette.

“They didn’t want any other uppity cities going down this road,” Handwerk says.

“This was a finger in the dike.”

The citizen group was able to settle into reaction

mode: Once the dumb, clunky messages came out, they took to their

emails and blog and pointed out every single lie. It wasn’t just an

opportunity to educate; it was an opportunity to draw on local pride

and, again, that spirit of audacity. “It was a lot of fun to watch,

waiting for them to say something else ridiculous and outrageous,” John

St. Julien remembers.

The citizen group was able to settle into reaction

mode: Once the dumb, clunky messages came out, they took to their

emails and blog and pointed out every single lie. It wasn’t just an

opportunity to educate; it was an opportunity to draw on local pride

and, again, that spirit of audacity. “It was a lot of fun to watch,

waiting for them to say something else ridiculous and outrageous,” John

St. Julien remembers.

One critical aspect, he adds, was the participation of Durel and Huval.

“To

have public officials willing to advocate out front, to be — in this

day and age — so forthrightly un-corporate, I was just blown away,” John

St. Julien says. “They were willing to say, ‘These are greedy

outof-town corporations.’” The “big boys” really would do just about

anything, as is evidenced by a story Huval tells. He was on Gov.

Kathleen Blanco’s broadband advisory council, and was at the State

Capitol for a meeting one day. “A Cox representative asked me to have

coffee in the cafeteria there. And this person told me that Cox was

creating a new director of operations position, and that he/she had been

asked to approach me to see if I was interested,” Huval recalls.

Cox offered that job to at least three others in Durel’s inner circle, Durel adds.

And some detractors haven’t stopped.

Tim

Supple has been a vocal opponent of the plan since its inception and

continues to be critical of the fiber system to this day

— even though he’s a fiber customer and calls it “a wonderful product.”

Supple

feels that most customers don’t need Internet at the speed and capacity

fiber offers, and that the plan was to make a lot of profit in

telephone and cable TV, markets he says are “drying up.” He insists on

comparing current financial statements to the feasibility study done in

2004 to determine if LUS Fiber could work.

“Everybody

can have an opinion, but nobody can have an opinion on the facts, and

the facts show losses of $50 million they have to make up,” Supple says.

The problem with Supple’s facts is they don’t match the figures.

The

feasibility study predicted that, by the fifth year of offering

services to both residential and business customers, telephone sales

would top $9 million, TV sales would be at $12.5 million, Internet sales

would be less than $5 million, and wholesale sales would be

approximately $2.7 million. That’s a total of $30.1 million.

But

the figures were, for the fifth year of sales: $4.8 for telephone,

$11.5 for television, $11.3 for Internet and $3.1 for wholesale. That’s a

total of $30.7 million. So while there was an over-estimation of

telephone sales, there was an under-estimation of wholesale sales and a

very large under-estimation (more than 50 percent) of Internet sales. In

the end, it’s a wash because the projected revenues are almost spot-on —

something one would not really expect to happen, since the feasibility

study did not take into account the delays and costs associated with the lawsuits filed by the “big boys.”

Also,

the “losses” referred to by Supple aren’t valid, either, Huval says.

Supple is trying to combine long-term debt and depreciation with annual

net income, and the two don’t mix, according to Huval. The required

depreciation is close to $54 million currently, but the “continuous

review” that Huval’s people have done projects only $5 million in needed

upgrades in the next 10 years. Fiber assets are on a depreciation

schedule of 30-40 years, but are like power lines in that they are more

likely to last 50-60 years.

Also,

the “losses” referred to by Supple aren’t valid, either, Huval says.

Supple is trying to combine long-term debt and depreciation with annual

net income, and the two don’t mix, according to Huval. The required

depreciation is close to $54 million currently, but the “continuous

review” that Huval’s people have done projects only $5 million in needed

upgrades in the next 10 years. Fiber assets are on a depreciation

schedule of 30-40 years, but are like power lines in that they are more

likely to last 50-60 years.

“Businesses

that survive make needed adjustments tied to real market considerations

— not based on a study that was based on some arbitrary requirement in a

state law,” Huval notes.

As far as the big boys go, a spokesperson for AT&T could not be reached for comment.

Cox

declined comment on the job offers to Huval and others and elected not

to address specific questions about the role it played in fighting LUS

Fiber.

Back to

the campaign for fiber, that alliance between the city administration

and the citizens’ group wasn’t all roses and rainbows. The citizen group

was promised assistance with funding that never came. The results of

the market

survey

done early on were never shared with its members, even though it could

have helped with their phone bank and door-knock planning.

And, for John St. Julien, LUS Fiber hasn’t reached its full potential.

“Did I expect it to look like this? Yes. Is

it what I most want? No,” he says of the current system. “But Terry was

nothing but forthright. He wanted a utility; reliable, low-cost

service. He was never all that interested in issues that I was

interested in, like the digital divide. ... What I really expected was a

conventional telecommunications offering, just as the electricity

company was conventional. There is no political under-the-table

involvement. There’s no favoritism. I’m fully cognizant of that, and I

like that, I’m good with that. But....”

John

St. Julien has wished for more aggressive and creative marketing, for

more progressive implementation — citywide WiFi for instance — but he

hasn’t seen that. (See related sidebar for an update on citywide WiFi.)

Handwerk

has wishes on the more technical side, in terms of LUS Fiber working

with co-ops like CLECO and SLEMCO to expand the system. But he feels

that even people who don’t have LUS Fiber are benefiting from the

system. “The other companies were forced to upgrade,” he says. “That

rising tide launched all these ships. You’re paying less today than you

would have, and you get better service.”

“From

the beginning, we listened to lots of ideas. Some of them, like the

peer-topeer Intranet idea, were ones we embraced and deployed. Some

ideas felt too radical and unpredictable for us to feel comfortable

with,” Huval says. “While ideas and visions were welcome, we knew that

our most important immediate task was to make this system a financial

success. We had to strike the right balance between technology and

financial viability.”

In

terms of profit, the delays created by the state statute and the

lawsuits aimed at shutting the project down hurt the most, he says.

“We entered this arena as underdogs.

We

had to fight for every success we achieved. We were forced to accept a

law that was going to make our entry into this business far more

difficult. We incurred lawsuit delay after lawsuit delay — delays that

impacted our entry into this competitive market for three years. I know

of no local government telecom system that has had to go through the

extreme challenges we encountered,” he notes. “If we would not have had

all these early legal impediments, we would have been on-line faster and

drawn in far more customers, more quickly. If we could have captured

the level of strong enthusiasm in those early years, there is no doubt

our revenues would have been stronger, and we could have been even more

creative and aggressive. ... Under the circumstances, there was not much

we could have done differently and still reach a successful business

result.”

So the battle

is ongoing, but right now, Durel says, “cash flow is positive.

Technically you can say it is still showing a loss. At the end of this

year you won’t be able to say that.”

Some

will still want to say it, and will say it — but to do so would be

disingenuous at best, he says. “I will never understand how anybody, a

councilman or a consumer, would think that hurting our system benefits

our people.”

Even

though the fiber system is, itself, an asset on so many levels, and has

forced better service and lower prices for our citizens — and that alone

is a benefit — Huval says profit is still critical.

“I think the citizens would want to see the system profitable,” he says. “They’ve made an investment in this system.”

Looking

back, Durel feels that fiber did turn out to be that defining

accomplishment, the one (along with the Horse Farm) of which he’s most

proud.

And let’s be

frank: Who knew at the time that Durel had it in him, that so early in

his political career he would risk so much on such a bold initiative?

No one. Except for Durel himself — and Terry Huval, of course.

“I

knew this had the possibility of transforming Lafayette — that 25 years

later, Lafayette would be a better place because of this,” Durel says.

“Even if fiber just breaks even, but we create thousands of new jobs

because of it, that’s a win.”