For years, the city said there was no money for the homeless. Now there’s lots of it. Billie Aschmeller has no doubt in her mind about what happened to Tim Hawker.

“He died from being homeless,” she says, adding: “You shouldn’t have to wait until you’re in a casket to have a permanent home.” Hawker, who was one of about two dozen homeless people who slept at Lincoln Library before the city ended the practice in June 2007, slipped into a diabetic coma on Tuesday, May 19; he died two days later.

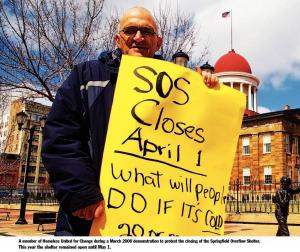

Days before Hawker’s death, another homeless man, named Howard Turner, also died after living on the streets. Friends and fellow homeless like Aschmeller believe that these men might still be alive if better services had been available to them. Although service providers agree that more could be done, they also say that too often people simply choose not to take advantage of the programs available to help them. Both groups are partly right. A count conducted in January 2008 by the Heartland Continuum of Care, which divvies federal Housing and Urban Development money between local groups, found 379 homeless individuals — 115 children and 264 adults.

At the time, there were seven unhoused individuals, 45 residing in permanent housing programs, 97 people in transitional shelters and 115 living in staying in emergency shelters.

The 2009 numbers will be released in June in conjunction with the unveiling of an updated “Mayor’s Ten-Year Strategic Plan to End Chronic Homelessness.”

In a city the size of Springfield, it seems that such a problem could be solved with strokes from a few pens. However, for years, both agencies and governmental entities have lamented the paucity of funds available to adequately serve everyone who needs social services.

Money hasn’t been the only problem. The Salvation Army, which knows how to raise cash as well as anyone, has wanted to expand its shelter operations for more than five years but came up against a number of roadblocks.

Quietly the tide now appears to be turning — and in some major ways. The Salvation Army recently announced its intention to purchase and remodel the former Horace Mann annex building at 100 N. Ninth Street. Plus, an unprecedented $1.1 million from the federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act is headed to town, earmarked exclusively to prevent homelessness and to rehouse those who had residences but fell back into homelessness.

The money was made available through the Department of Housing and Urban Development under a program known as Homelessness Prevention Rapid Rehousing. Of the total, $512,000 is being provided directly to the city with another $592,000 coming from the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity.

The federal money will go a long way toward addressing homeless problem in Springfield. And for the first time, advocates, city officials, service providers and homeless people themselves say an end to homelessness is in sight.

Much of the pressure will be taken off when the Salvation Army more than doubles the space of its current shelter to 80 to 100 beds. In early May, the church unveiled plans to purchase a three-story building downtown to serve as administrative headquarters, a community center, and homeless shelter.

The total price tag is $6.8 million (of that, $3.4 million represents the purchase price) for the project. The rest is for remodeling the 60,000-square-foot building that once housed Horace Mann employees as well as expansion of several services the organization provides. For example, they’ll be able to able to purchase a deep freezer to use in the food pantry.

On Wednesday, May 20, the Springfield Planning and Zoning committee approved the variance request needed to use the space for residential purposes. In June, the city council will decide whether to give the project final approval.

So far, no opposition has been voiced, which in itself is a minor miracle. In January 2006 — on the same night the city council approved Springfield’s smoking ban — aldermen rejected the Salvation Army’s pro- continued on page 12 |