Is the county jail responsible?

Tiffany Rusher spent four months in a cell the size of a small bathroom.

Then, she killed herself. The list of Rusher’s diagnoses over the years was long. Depression. Antisocial personality disorder. Post-traumatic stress disorder. Bipolar disorder. Schizoaffective disorder. Borderline personality disorder.

With a history of self harm dating as far back as 2014, Rusher was serious about suicide. In 2017, she succeeded while in the custody of the Sangamon County jail. Now, her mother, in separate federal lawsuits, is suing the county and the state, claiming that her daughter’s death was preventable and that the lack of treatment for mental illness amounted to unconstitutional torture.

It is, already, a big-money case for the county, which has spent six figures on legal fees. With trial set for next year, there have been no serious settlement talks. “I don’t think we did anything wrong,” says Sangamon County Board member Craig Hall, who chairs the board’s civil liabilities committee that receives monthly reports on lawsuits and reviews legal strategy. “We have good attorneys. I listen to good attorneys. They’re saying it’s an unfortunate thing that happened, but we are going to keep pursuing the case, and it will probably go to trial.”

Alan Mills, an attorney for Rusher’s mother, says that the plaintiffs, also, are prepared to go to trial. He declined to ballpark what a fair damage award might be.

“That’s what we pay juries and judges for,” he says.

“Descent into madness”

Sometimes, Rusher scared herself.

In 2014, while an inmate at Logan Correctional Center in Lincoln, Rusher, saying that she wanted to hurt herself, asked to be placed in restraints, according to her mother’s lawsuit against the state. She spent more than three years in prison. By the end of her stay, she was living alone in a cell, with guards watching her 24/7 to prevent her from killing herself.

According to her mother’s lawsuit, Rusher hadn’t been diagnosed with a mental illness before she became a state inmate in 2013. She had been a crack-addicted prostitute who performed oral sex on three boys for money in a Decatur basement, which earned her a five-year sentence for aggravated sexual abuse of a minor and a spot on the state sex offender registry.

Rusher served every day of her sentence. The longer she stayed in prison, the worse she got, according to her mother’s lawsuit. She swallowed batteries. Then a pen. She tried to strangle herself. She was provided therapy, but each time she tried hurting herself, she was placed in solitary confinement, which undermined whatever therapy she’d gotten, according to the lawsuit.

More than two years into her prison stint, after another suicide attempt, Rusher was placed under constant watch. She had become so dangerous to herself that she needed to be kept in isolation, with a guard assigned to watch her every minute.

“It is an accepted tool for mental health treatment, but it is meant for short periods of confinement only – typically for a few hours – so that a person in a

mental health crisis can be evaluated, a treatment plan can be

developed, and the person can thereafter be hospitalized or returned to

some form of residential or outpatient care,” lawyers for Rusher’s

mother write in their lawsuit against the state. “In the most extreme

circumstances, it is acceptable to keep a person in ‘crisis’ confinement

for a few days, at most.”

Rusher

spent the remaining eight months of her sentence in a Logan isolation

cell under constant watch, stripped naked except for a suicide-proof

smock – a turtle suit, in jail lingo – made from heavy tear-proof nylon

with fasteners, typically Velcro, that can’t be swallowed or otherwise

used to cause harm. She was restricted to soft foods and had no books or

other possessions, according to her mother’s lawyers, who say that cell

lighting was always on. When she defecated, she had to ask for toilet

paper and let a guard watch while she wiped herself, the plaintiffs say,

and guards also observed when she changed sanitary napkins. Each week,

she was interviewed for 30 minutes by a psychiatrist to determine

whether dosages of psychotropic drugs should be adjusted. Occasionally,

according to court documents, she was allowed to attend 30-minute group

therapy sessions, but no more than once a week, and if she tried harming

herself, sessions would be canceled as punishment.

“The

short sessions amounted to an infrequent and irregular interruption to

the days and weeks on end that Tiffany was forced to spend alone in a

bare cell, and to make matters worse, when she was allowed to attend the

sessions, she was rarely, if ever, allowed to speak,” attorneys for her

mother write in the lawsuit against the state. “Instead of providing

her with the treatment she desperately needed, defendants chose to keep

her in isolation and monitor her condition, carefully documenting her

descent into madness.”

The

Logan medical staff knew that Rusher’s was a special case. Shortly

after she was placed under constant watch, the staff concluded that she

suffered from an acute mental health crisis, her mother’s lawyers say,

and was “at severe risk” of harming herself. “They also identified her

as one of only a few dozen patients within the entire (Illinois

Department of Corrections) whose mental illnesses were so acute and

dangerous that they required full inpatient-level mental health care,”

the lawyers write. Rusher belonged in a mental institution, not a

prison, lawyers say, and the state’s failure to provide proper treatment

amounted to torture and a violation of her constitutional rights.

Rusher’s

condition deteriorated while in solitary confinement, according to her

mother’s lawsuit. She cut herself. She bit herself. She banged her head

against her cell walls and attempted suicide. She didn’t object when her

sentence expired and the state sought involuntary commitment to Andrew

McFarland Mental Health Center and so she was considered a voluntary

patient at the

Springfield mental health facility, where lawyers for her mother say her

condition improved. She received therapy and wasn’t kept in isolation.

“In

short, Tiffany received the treatment that the defendants should have

provided for her, instead of placing her in solitary confinement for

over eight months and causing the injuries and damages described

herein,” lawyers wrote.

Allegations

in the Rusher lawsuit against the state parallel claims in a

class-action lawsuit filed on behalf of mentally ill inmates who say

they’ve been housed in solitary confinement, put in restraints and

denied treatment for serious mental illness. In 2018, a federal judge

issued an injunction, finding that the lack of treatment for mentally

ill inmates was unconstitutional. He ordered improvement and assigned a

monitor to produce progress reports.

“High risk”

After

seven months at McFarland, Rusher was arrested and sent to the Sangamon

County jail after altercations with fellow residents and staff at the

mental health facility.

In

a memo sent to the jail after Rusher’s 2016 arrest, McFarland employees

summarized her history both at the mental health facility and Logan.

At

least 10 times during an 18-month period in prison, McFarland staff

wrote in the memo to county jail staff, Rusher had attempted suicide.

The attempts had included self-strangulation with a towel. More than two

dozen times, she had otherwise attempted to harm herself by swallowing

pens, toilet paper, eating utensils and toothbrushes, McFarland staff

wrote.

While at

McFarland, the mental health center’s staff told jail personnel, Rusher

twice had tried to strangle herself and also had swallowed large objects

that were removed from her body by medical

personnel. The day after Rusher was booked into the jail, a McFarland

nurse followed up with a phone call, according to the lawsuit against

the county, telling jail staff that Rusher had a history of

self-asphyxiation attempts and that she’d received one-on-one care at

the state mental health center.

Jailers posted a paper notice on Rusher’s cell:

“HIGH

RISK. Tiffany Rusher. Hard Tray/Cup. 7-10 squares of toilet paper at a

time. Subject will ingest foreign objects. High risk uniform/ blanket

only. Do not be alone with subject.” As at Logan, she was stripped

naked, given a blanket and kept in solitary confinement, with no

possessions, social contact or meaningful treatment, according to her

mother’s lawsuit. A jail doctor detected bipolar disorder and

schizoaffective disorder.

Solitary confinement worsens mental illness, according to lawyers for the plaintiff who refer to standards promulgated by

the American Correctional Association, the Association of State

Correctional Administrators, the American Bar Association and the

National Commission on Correctional Health Care Standards for Mental

Health Services in Correctional Facilities.

“The

defendants’ policies, and their conduct, flatly ignored and

contradicted this accepted knowledge,” lawyers for Rusher’s mother write

in the lawsuit against the county, several employees and Advanced

Correctional Healthcare, which held the contract to provide medical care

to county inmates. “It was the policy of the Sangamon County Sheriff’s

Office to place persons suffering from mental illness or in danger of

suicide in solitary confinement for indefinite periods.”

According

to the lawsuit, the sheriff’s office had an agreement with an unnamed

outside entity to allow transfer of mentally ill inmates to appropriate

settings if their needs could not be adequately addressed

at the jail, but no transfer to a mental health facility outside the

jail was considered for Rusher. “(I)nstead, these defendants arranged

for Tiffany to be placed in solitary confinement, where they knew she

would be harmed instead of helped, from December 2016 through March 18,”

lawyers for the plaintiff write in their lawsuit.

Mills

said he didn’t know the name of the entity that could have taken Rusher

from the jail. A state mental facility, he said, should have been an

obvious choice.

An orange towel

County jailers soon encountered the same challenges with Rusher as their counterparts in state prison, the plaintiffs allege.

Less

than a month after she was booked into the jail, Rusher swallowed a

plastic spoon, necessitating a trip to Memorial Medical Center. A week

later, she tried strangling herself with a strap from a protective boot

she wore over an injured foot. Ten days later, she was returned to

Memorial after swallowing a toothbrush. Less than a week later, she

tried swallowing an apple core. One week later, she was placed in

restraints after she chewed on one of her hands until it bled. The day

after she got out of restraints, she swallowed mattress stuffing. Then

she stuffed toilet paper up her nose and said that she couldn’t breathe.

She also scratched her arms on the underside of a concrete bunk until

they bled, prompting another stint in restraints.

Three

days after swallowing a plastic bag, Rusher asked guards if she could

take a shower. A sergeant granted approval. She was on the cusp of

freedom. The day before, the public defender had reached a deal with

prosecutors: Rusher would plead guilty to battery, be granted probation

and then be released to a friend who had promised her a place to live.

Two

guards escorted Rusher to a shower room down the hall from her cell and

behind a closed door, according to the lawsuit. Rusher showered alone,

out of sight of guards. Guards gave her an orange towel to dry herself

behind a closed door. Without supervision, she put on turtle suit. She

was then returned to her cell, which was not in direct sightline of jail

staff. Guards were supposed to check on her every 15 minutes.

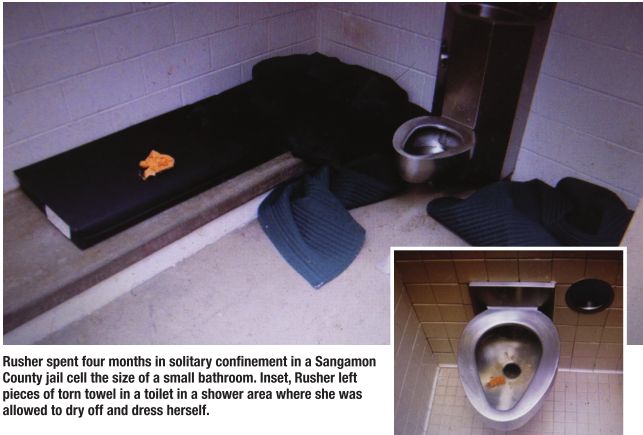

If

there is a smoking gun in the case, it might be torn bits of orange

towel that Rusher left behind where she’d been allowed to dry off and

dress without anyone watching. “Photos taken by investigators in the

shower area show that anyone who inspected the shower area after Tiffany

dressed unsupervised would have seen the bright orange threads and

realized that Tiffany tore the towel in some way while she was alone,”

her mother’s lawyers write in the lawsuit.

A

guard, the lawyers say, noticed that the towel Rusher had left behind

in the shower was torn, but did not determine how it had happened or

check the dressing area where orange pieces of torn towel were in the

toilet.

“Instead of conducting any

sort of sweep or inspection [the guard] simply escorted Tiffany back to

her cell,” lawyers write. “There was then a prolonged period, lasting

approximately 15 minutes, during which Tiffany was unsupervised. None of

the defendants responsible for monitoring Tiffany…checked on her. She

used this time to strangle herself inside her cell.”

Near

death, Rusher was taken to St. John’s Hospital, where she died 12 days

later, after being disconnected from life support. She was 27. The

coroner determined that she’d committed suicide with a strip of torn

towel smuggled from the shower.

The jail’s mistakes, plaintiff’s attorneys say, include failure to provide rip-proof towels to a suicidal inmate.

“It’s just a total breakdown in security here,” Mills says.

“It’s not complicated”

The last lawsuit filed after a Sangamon County jail death did not end well for taxpayers.

In

2014, the widow of A. Paul Carlock, who died in 2007, settled for $2.6

million, with the county paying its lawyers a like amount as the case

dragged on. Between the settlement and legal fees, it was the most

expensive litigation in county history. The plaintiff had claimed poor

medical care and rough treatment by guards, who allegedly killed Carlock

during a struggle that began when he refused to put on a shirt. A judge

had repeatedly urged settlement talks, but the county resisted, with

officials asserting that settling would encourage future lawsuits by

establishing the county as an easy mark.

So

far, the county has spent $235,000 defending the Rusher lawsuit,

according to Sangamon County Administrator Brian McFadden, with a trial

date set for Jan. 19, 2021.

Six-figure payouts aren’t unusual when inmates commit suicide.

In

Christian County, the sheriff’s office in 2017 reached a $550,000

settlement brought by the family of an inmate who killed himself in 2011

after being deemed a suicide risk. After the death, the county hired

Advanced Correctional Healthcare, a codefendant in the Rusher lawsuit

against Sangamon County, to supply a mental health professional for the

Christian County jail. A federal jury in 2018 awarded $301,000 to the

brother of a man who hung himself in the St. Clair County jail in 2014

after reportedly telling a guard that he was suicidal. The sheriff

insisted that the jury got it wrong; the surviving brother told the Belleville News Democrat that he’d rejected an $800,000 settlement offer. Last year, St.

Clair

County settled a second lawsuit, paying $850,000 to relatives of a

mentally ill inmate who hung himself in the same jail, also in 2014.

Federal

juries in Springfield have proven receptive to inmates who have claimed

substandard health care. In December, a jury awarded $11 million to

William Dean, who claimed

that the state’s health care provider hadn’t promptly diagnosed cancer

while he was an inmate at Taylorville Correctional Center. In 2016, a

jury awarded $300,000 to Vincent Trimble, who said that he waited years

to get proper treatment from prison doctors for a back problem that

included a herniated disc.

Sheriff

Jack Campbell, who was not in office when Rusher killed herself, said

that he didn’t want to answer specific questions on the lawsuit because

litigation is pending. “We have to look at each case, on its own merits,

and determine what the exposure is to the county and that sort of

thing,” Campbell said. “We can’t get into the minds of jurors and judges

about how they make the decisions they do.”

Mills points out that Rusher’s suicide attempts weren’t successful at Logan or McFarland.

“If

you’re going to put someone in jail – and remember, this is somebody –

then you take on the obligation of taking care of them,” the lawyer for

Rusher’s mother says. “If the county couldn’t do it, they should have

transferred her to some place that could.

“It’s not complicated.” Theresa Powell, attorney for the county, declined comment.

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].