All photos courtesy of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

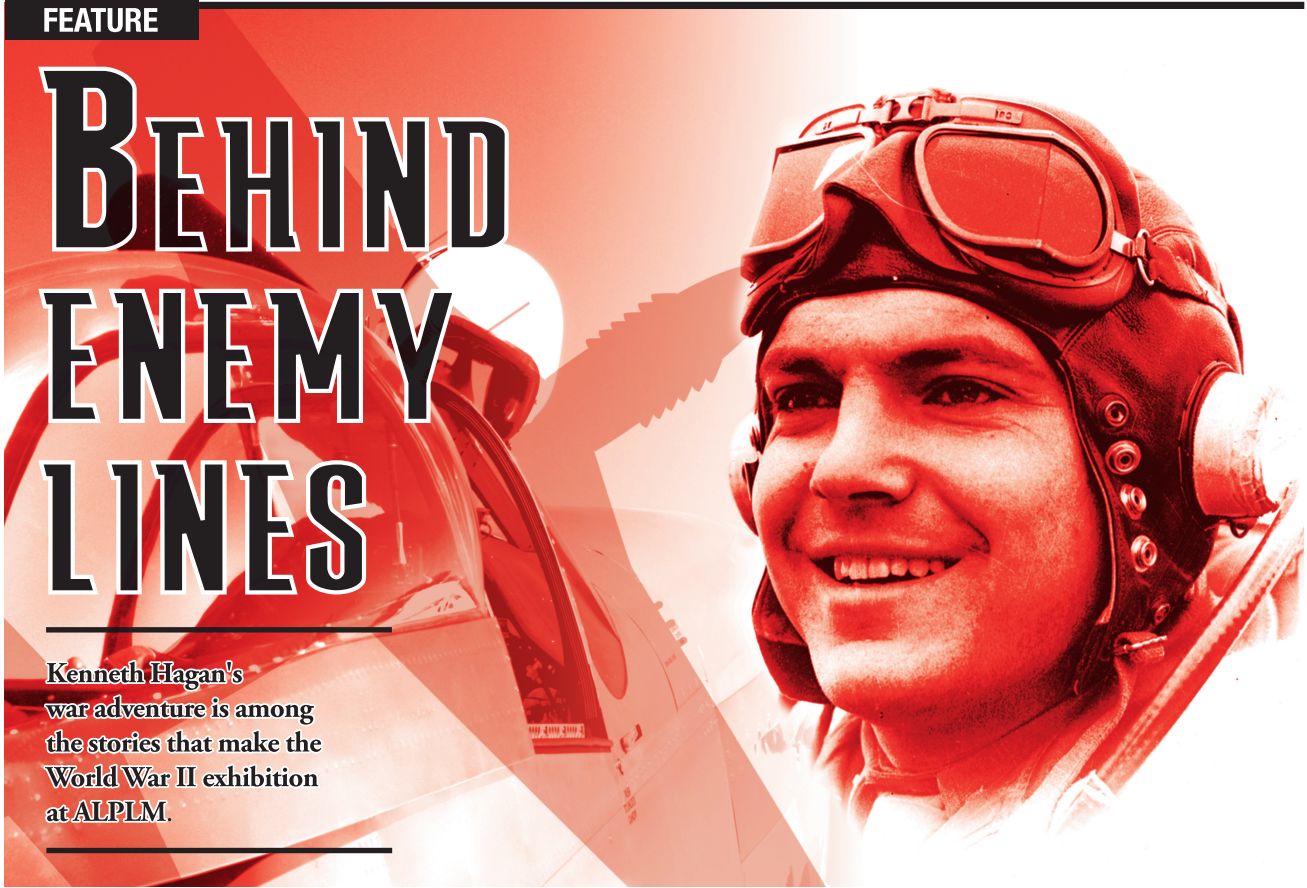

His picture is in a case along the back wall in the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Museum’s new exhibition on World War II. He is handsome in his pilot’s helmet and cheerful, confident smile, and so very, very young – only 21 when the photo was taken. A picture of his P-51 Mustang fighter plane is there, too – “My Bonnie,” named after the beloved wife who waited for him over the ocean, back home. These pictures come out of his wartime scrapbook. The clippings and photos within are all that is left of him now; the only clues left behind with which to piece together his life.

What they tell us is this: Kenneth Hagan was a fighter pilot who survived behind enemy lines in France only to die too young under mysterious circumstances in Florida. Like so many members of his generation, he was an ordinary, all-American kid who found himself in extraordinary circumstances during the war.

Under those circumstances, Kenneth Hagan became a hero. Though history has forgotten him, he deserves to be remembered. This is his story.

Small town boy

Hagan was born in Lincoln, Illinois, in 1923.

He was the fourth child and first son of Ernest, an electrician, and Anna, who kept their modest home on North Logan Street. He attended Lincoln High School, where he lettered in varsity football and was a member of National Honor Society before graduating in 1941.

Hagan was working as a draftsman at the utility company where his father worked when Pearl Harbor was attacked. The following spring, he was one of 10 Springfield-area young men chosen for training as an aviation cadet by the army air corps. In March of 1942, he kissed his sweetheart, Bonnie Edwards, goodbye and headed west for pilot training.

By March of 1943, Hagan’s training was complete, and he was commissioned a second lieutenant. That summer, Bonnie took the train out to meet him in California, and the pair were married in San Francisco on June 14. They spent just five months together before Hagan was sent to England in November; Bonnie returned to Illinois to live with her parents in Broadwell.

Hagan was assigned to the 357 th fighter group of the 362 nd fighter squadron. Based first in Reydon, then in Leiston, England, the 357 th flew P-51 Mustangs to escort bombers on raids over Germany. In the spring of 1944 they set a record for shooting down 59 German planes in 30 days, two of them by Hagan.

To encourage further success in combat, Hagan’s squadron leader, Joseph Broadhead, sent letters to Hollywood studios asking their starlets to help boost his pilots’ morale.

He promised that his squadron would “perform the following in exchange for the following:

1. Destroy 1 German plane in the air for every pair of autographed step-ins.

2. Destroy 1 German plane on the ground for every autographed brassiere.

3. Destroy 1 German troop train for every autographed princess slip.

4. Destroy 1 bridge or 1 flak tower or 1 warehouse or 1 staff car for every autographed pair of hosiery.

Think we’re kidding?” Broadhead concluded, “Try us.”

Hollywood

took them at their word, and soon undergarments started arriving from

the stars. Rita Hayworth even sent an autographed slip in return for the

promised destruction of a German troop train.

It

wasn’t all levity on the fighter base in England, however. Hagan and

his fellow pilots knew all too well how dangerous their missions were;

they had only to look at the empty chairs in their officers’ club to be

reminded that each mission they flew might be their last. Hagan’s best

friend in the squadron was Fletcher Adams of Louisiana. On May 30, 1944,

he was escorting a crippled bomber back from a raid when he was shot

down near Bernberg, Germany. He bailed out of his aircraft but was

captured and murdered by German civilians on the ground, leaving a wife

and infant son to mourn him.

Behind enemy lines

On

June 17, 1944, less than two weeks after D-Day, Hagan, now a captain,

was providing air support on a flying mission over Normandy when he

suffered engine failure and crashlanded in a wheat field outside the

tiny village of Beauchene. His plane turned over and split in half,

though Hagan was fortunate to escape with only a scrape to his forehead.

He made his way to a nearby farm, where he was given a change of

clothing and put in contact with the French Underground. After receiving

new clothing, he was taken to the country house of Yvette Dubocq.

Dubocq

was a 39-year-old former French intelligence officer. She and her

partner, Jeanne Cochin, now worked for the Resistance in Nazi-occupied

France. When Hagan arrived, they were already sheltering two American

pilots, Joseph Porter and Duffy Kalbfleisch, who had been shot down the

previous April. They were operating in direct defiance of the occupying

German forces, who posted an official notice: “It is forbidden to hide,

lodge, or help in any manner any member of enemy forces (specifically

air crew members or enemy parachutists). Noncompliance is punishable by

DEATH.”

When he

arrived at Dubocq’s house, Hagan was greeted warmly by his fellow

American aviators. Dubocq hid his military uniform and gave him forged

identity papers. She was amused to see that he had had a “V” for

“victory” shaved into his hair during a recent haircut.

“I gave him formal orders never to remove his Basque beret,” Dubocq later recalled.

Within

days, the Underground determined that the three American pilots should

be taken to nearby Caen to attempt to rejoin the Allied front. On June

20, the group had their photo taken with their French hosts and enjoyed a

last meal before their departure at dawn the next day. “Will they get

through? Will they make it?” Dubocq thought to herself as she watched

their retreating figures the next morning.

Three

weeks later, Dubocq was in her orchard when she saw a familiar

silhouette appear. It was Kalbfleisch, who said that Porter, Hagan and a

fourth American, Ed Nabozny, were hiding nearby. Dubocq ran to them and

found them with blistered feet, dirty, exhausted and starving. As she

dressed their wounds and fed them, the airmen filled her in on their

travails.

After they left Dubocq’s

house they had made their way to Caen, where they sheltered in the

evacuated, bombed-out house of one of the Resistance fighter’s parents.

They were told that it was impossible to get through the enemy line and

that their best hope would be to hold on until the Allies liberated the

town.

For three weeks

they hid, short on food and clean water, as German forces occupied the

city and Allied forces bombarded it. On July 14 they lost contact with

the Resistance. Isolated and afraid, they decided to make their way back

to Dubocq’s house. They traveled for two days through intense heat with

no food, tattered clothing and only a small, hand-drawn map to guide

them.

Dubocq gave them

shelter, but her house was far from safe; German soldiers had now

requisitioned it and were occupying some of the bedrooms. For two weeks

the American aviators hid in plain sight on Dubocq’s estate, posing as

French citizens in a deadly game of cat-and-mouse with the German

soldiers who were constantly coming and going.

When

two S.S. officers who were fluent in French joined the occupying

soldiers in Dubocq’s house on Aug. 2, 1944, Dubocq knew that she could

no longer safely hide the Americans. With a heavy heart, she sent them

to the town of Domfront with a resistance fighter named Andre Rougeyron.

Months

later, she received a letter from Hagan, who filled her in on what

happened after they left. They were taken to Rougeyron’s chateau in

Domfront, but fled the next morning when Rougeyron was arrested by the

Gestapo. After hiding in a baking hut in the countryside for three days,

the sound of the approaching Allied army grew closer. On Aug. 7, they

were able to rejoin the American lines in the small town of Lonlay.

Their odyssey behind enemy lines was over.

“Dearest,

they can’t keep a good man on the ground / probably see you soon /

writing immediately/ you do the same / all my love Kenny,” Hagan

telegraphed to his wife.

Aftermath of the war

The

day after he rejoined the American forces in France, Hagan was flown

back to England. By Sept. 2, 1944, he was back in the United States. He

spent three weeks on leave in Lincoln with his wife and parents before

reporting for duty at his new assignment at Tyndall Field in Panama

City, Florida.

This

time, Bonnie was with him. They rented an apartment a block from the

beach, where they spent lazy days in the sun, sometimes alone, sometimes

with friends or visiting family. Letters came from France. One of the

Resistance fighters who sheltered him spoke of the privations in his

war-torn country and spoke nostalgically of the time they shared

together, “an epoch where we lived for something that was worth living

for and life had taste and pepper.” Yvette Dubocq wrote to tell Hagan

that Andre Rougeyron had been tortured by the Gestapo and taken to the

concentration camp at Buchenwald before escaping to freedom during an

Allied bombing raid. And she assured him that, despite the danger she

and Jeanne faced in doing so, “it was a privilege for us to take the

chance to help you out.”

To

Bonnie, Dubocq wrote, “Under the mild climate of Florida, near your

dear Kenny, be very happy little Mistress, and believe there is nothing

so gracious as a laugh in the sun, nothing is more restful than a

beautiful union of the heart.”

Postscript

From the Daily Illinois State Journal, Dec. 14, 1946: “Panama

City, Fla., Dec. 13. (AP) The body of Capt. Kenneth Hagan, 23-year-old

army fighter pilot with an outstanding war record, today was found

hanging in thick woods near a lonely road to the gulf…The provost

marshal notified Panama City police early today that Hagan had been

missing since 9:30 a.m. Thursday. Later an abandoned car was found on a

little traveled road skirting the base. The car was identified as

Hagan’s and the body was located shortly afterwards.”

Erika Holst is the Curator of Decorative Arts and History at the Illinois State Museum.