Horse racing struggles in Illinois

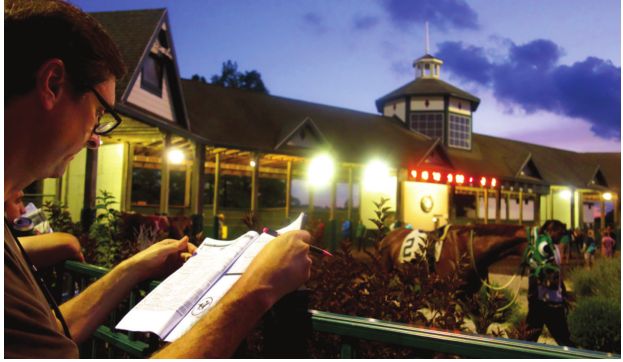

Shortly after the first race, a thunderstorm descends on Arlington International Racecourse, just north of Chicago.

An hour before post time, families toting coolers had streamed into the track, paying $10 apiece for admission, less for kids and extra to reserve spots alongside the final stretch, a football field or so from the finish line and safe distance from the tawdry business of gambling, without which no one would be here. It is Renaissance Faire Family Day, with pretend jousting, pony rides, a petting zoo and more, alongside a soldout picnicking area where a staggering amount of sandwiches, potato chips and bottled water, with an occasional birthday cake, were unpacked an hour ago in preparation for a day at the races.

Now, this.

As clouds approach, folks repack and scurry to the grandstand, but a dozen or so make it no farther than a large tent where draft beer costs $7.50 and Bloody Marys come in plastic cups. Men in drenched suits and ties appear through the deluge, not running but certainly hustling, and throw canvas covers over electronic terminals that gobble money from bettors. The tent’s frame and guy wires and stakes are made from metal, which shrieks and grinds in the wind as parts rub against each other. No reach is spared rain – it’s not clear whether it is blowing in from the side open to the track, through a billowing roof or both.

“It’s not safe,” a guy dressed security-guard in navy blazer and grey slacks tells us, advising that everyone flee, through the deluge, to sturdier shelter. He offers free plastic garbage bags that can be turned into ponchos. They charge 50 cents for a pencil if you lack means to take notes from the race program, which contains records of horses, records of jockeys, records of trainers, selling prices, pedigrees, times in recent workouts, etc.

Two betting terminals remain uncovered and beckoning while flat screens show races from tracks elsewhere with sunny skies. There is a rumor of half-price beer. How bad can this be? I head to the bar, where Kurt Kresmery, who owns an Elgin property management firm, is nursing a Coors Light. What, I ask, is a guy like you doing in a place like this? He tells me a story.

A few years ago, stumped for a Father’s Day gift, a friend who was into horse racing suggested that Kresmery buy his dad a share in a racehorse.

Such so-called fractional ownership of horses spreads risk and has become common in a sport where upkeep is expensive and returns uncertain. Thoroughbreds created a point of connection between father and son, neither of whom had been race fans, that endured to the end. Even today, his father gone, Kresmery owns part of a horse that is racing this afternoon at Ellis Park in Kentucky.

Before it happens, a horse race can generate endless speculation, with determined bettors considering such esoterics as heat and humidity to help guess how a horse will perform on any given day. The action lasts a minute or two, and it takes four hours to run a program. There is plenty of time for conversation, and Kresmery recalls his dad enjoying afternoons at the track and occasional forays to

off-track-betting parlors to watch horses that were partly his. In

hospice, Kresmery recalls, his dad held his hands as if grasping reins,

trying to mimic a jockey’s bounce when his son told him about an

upcoming race. “He died the next day,” Kresmery says. It’s not the sort

of tale one hears in video gambling joints.

An industry in crisis

If

video slots are the crack cocaine of gambling, horseracing is Geritol,

and that’s part of the challenge facing horse racing as the fan base

shrinks and ages. There are just seven races today at Arlington, three

short of a traditional 10-race program. “Look at this,” Kresmery says,

pointing to a stat sheet for the fifth race, which will be contested for

an $11,500 purse. “It’s nothing. Our horse ran third in Kentucky a few

weeks ago and we got $10,000.” Even that, Kresmery maintains, isn’t

enough to break even, at least for long.

Purses

are the heart of racing, which, at its core, is all business. Arlington

is the state’s premier track, where the grounds are spotless,

landscaping is immaculate and neither shorts nor athletic shoes are

allowed in the Million Room restaurant, the fanciest of nine eateries.

In 1981, Arlington became the first thoroughbred track in the world to

offer a $1 million purse. With Bill Shoemaker aboard, John Henry won the

inaugural Arlington Million and was named Eclipse Horse of the Year.

They still run the Arlington Million each August, but it is a rare

bright spot. Purses elsewhere are lower and crowds smaller, with

statewide attendance at tracks dwindling from 3.9 million in 1995 to

less than 909,000 last year.

Locally,

the amount bet last year at Capitol Teletrack in Springfield, one of

two dozen offtrack betting sites in Illinois, was less than half what

was wagered at a Lucy’s Place gambling parlor with five video machines a

few blocks away on Wabash Avenue. Racing at the state fair also has

declined. In 2018, a quarter-million dollars was wagered during four

days of harness racing at the fair. In 1995, $1.3 million was bet on 82

races run over six days.

Downward

trends are statewide and national. Since 1990, when more than $1.25

billion was wagered on horses in Illinois, the amount bet on horses, or

handle in racing’s parlance, has fallen to $573.5 million, including

bets placed outside the state by gamblers who can watch races across the

land via simulcast broadcasts. In 2018, just 11 percent of money

wagered in Illinois on horses ran their races in the Land of Lincoln.

The state is down to three tracks, two fewer than in 2015, when a pair

of Chicago-area harness tracks shut down. That same year, an East Moline

track that last held a live race in 1993 gave up after years of

simulcasts, ending resurrection hopes.

“The

horse racing industry in this state is about to fall and crumble and

deteriorate and go away – that’s just how drastic it is,” state

Department of Agriculture Director John Sullivan told state senators

during a budget hearing last spring.

It’s

an industry worth saving, Sullivan argued. Since 2000, the number of

state-issued licenses for occupations ranging from grooms to owners has

shrunk from 11,000 to 4,000, but still, Sullivan testified, horse racing

generates $1 billion a year in economic activity, considering grooms,

blacksmiths, feed stores, veterinarians and scores of other jobs.

“The

jobs generated by this industry, they’re very real,” Sullivan told

legislators. “Anything you can do to help them would be appreciated.”

Legislators

and Gov. J.B. Pritzker delivered with an expansion of gambling that

includes sports betting at tracks and the potential for racecourses to

become full-fledged casinos. There’s a provision for a new standardbred

track, despite closures in recent years. Fairmount Park in Collinsville

could have as many as 900 video

gambling machines and seats at blackjack tables and other table games.

Arlington and Hawthorne Racecourse, both in the Chicago area, could each

have as many as 1,200 spots for gamblers to make bets on machines,

cards or other table games. By comparison, no existing casino has 1,100

video gambling terminals, according to the most recent report from the

Illinois Gaming Board, and 317 table games operate in the state’s 10

casinos, most of which are operating fewer gambling machines than

authorized. Video gambling has not previously been allowed at tracks,

where millions of dollars in wagers are accepted on nothing but horse

races.

A

share of the take from casino-style gambling at tracks would go toward

purses to help the state’s racing industry, but there is a string:

Tracks with casinos can’t abandon horse racing and might have to

increase the number of races in exchange for slot machines and casino

games. The law requires 700 races annually at Fairmount Park if the

track wants video gambling and table games; last year, the track’s

season lasted 36 days, with many dates including fewer than 10 races,

and so the number of races might double. Arlington and Hawthorne

together would need 174 thoroughbred racing dates each year if both

tracks got casino gambling; last year, the tracks combined had 125

thoroughbred dates. Harness racing tracks, where comparatively stocky

standardbreds pull wheeled carts called bikes, would have to have 100

race dates each year, a threshold already met by Hawthorne, which last

year held 105 harness racing dates. Minimum race date provisions can be

waived by the Illinois Racing Board if horse owner associations agree,

the law says, so long as the integrity of the sport isn’t affected. The

board also could waive racedate minimums if there aren’t enough horses

or if purse levels aren’t sufficient.

All

this gambling at tracks would come in addition to six new standalone

casinos authorized by state legislators, more video gambling terminals

in bars and restaurants and more video gambling and table games at

existing casinos that now don't have all the tables and video gambling

terminals previously authorized. The law also includes provisions for

online sports gambling.

“It’s a lot of money”

The new law is the talk of the backstretch at Hawthorne the day after the governor signs the bill. It is, folks say, salvation.

“You

can just feel the mood of the people around here,” says trainer Steve

Searle, whose father, grandfather and great-grandfather also trained

horses. “We were about flat-lined. Seriously. It was as bad as it could

get.”

By definition,

horses anchor the sport, but the number of Illinois-bred animals has

plummeted, from nearly 4,500 foals born in 1985 to 300 last year.

Lawmakers have adjusted by changing the definition of Illinois horses

eligible to compete in races limited to animals born and bred here. A

2018 law made possible by artificial insemination removed a requirement

that standardbreds in races limited to Illinois-conceived-and-foaled

livestock must come from mares that were impregnated in Illinois and

that gave birth within the state.

“They

got a little creative with the born and bred,” observes trainer Angie

Coleman, who’s made her living with racehorses for seven years. Before

that, she lived in downtown Chicago. She once sold cars and also has

worked for a credit card company. The backstretch, she says, is a more

welcoming environment for women than other places she’s

worked where men were in charge. “I had those kinds of challenges when I

had a real job, but not here,” she says.

Plenty

of kids – the track provides housing for workers and families – and

women inhabit the backstretch. Drivers wear overalls, some in need of

washing, instead of silks and are of normal shape and size. Weight

doesn’t much matter in harness racing, where bikes bear the load. A

three-legged black cat named Trifecta roams the barns. If folks who earn

their livings from racehorses don’t care about animals, someone forgot

to tell trainer Rob Rittof, who found the cat in a parking lot with a

mangled paw and took it to a vet.

“It’s

a community back there,” says Jim Miller, Hawthorne publicist and race

analyst. “You’d be surprised to see the school bus roll up every

morning.”

It’s a

grueling schedule. Races start at 7:30 p.m. and can last until midnight,

but horses don’t sleep late and need to be brushed and fed and

exercised and treated for any medical issues. The track provides the

stage, backstretch folks put on the play. They don’t appear rich as they

prep horses for races, water down ones fresh from the track and watch

races unfold on 25-inch box televisions from an era before flat screens.

“The

labor side, the horse owners, need to have a chance to make money on

it, or at least break even,” says David McCaffrey, executive director of

the Illinois Thoroughbred Horsemen’s Association.

Racinos

in Indiana, Kentucky and other states have sucked jobs directly from

the Illinois horseracing industry, McCaffrey says. Last year, purses at

Illinois racetracks totaled $34.5 million. Slots and casino games,

McCaffrey figures, could boost purses by $20 million at each of the two

Chicago-area tracks.

“It’s a lot of money,” he says. “It’s going to be a terrific boon.”

While

hopes are high for more foals and bigger purses and more races, no one

seems to know whether the expected surge of slots at tracks will create

more horse bettors. Playing horses is as easy or difficult as you want

to make it. While some go by names or odds alone, the serious horse

player can spend hours studying racing forms, videos of past

performances and weather forecasts. A horse might appear a dog, but wait

a minute: He broke late from the starting gate and was bumped in his

last race but still gained ground at the end, plus he’s got a new owner

and trainer with a reputation for turning also-rans into contenders.

Never worn blinkers before? Hmm. And he does better on a synthetic

surface than natural dirt.

You

can hit the “play” button on a video gambling machine every few

seconds, but racing runs on a more relaxed schedule, with starts every

30 minutes. Small-time bettors can spend an afternoon at the track and

lose less than $50. “It’s a thought process, but that’s the beauty of

it, by the way,” McCaffrey says.

No

one seems to know whether casinos at Illinois tracks will create horse

bettors. In Ohio, the handle has gone down since the state legalized

racinos to subsidize racing. The Buckeye State’s first racino opened in

2012. In 2014, $166.8 million was wagered at Ohio race tracks; last

year, with seven racinos in full swing, the handle dropped to $150.8

million.

Death hurts

Past

efforts to bolster racing in Illinois haven’t met with universal

acclaim. “I was probably the only guy who was completely against

simulcasting,” says Clark Fairley, a standardbred trainer at Hawthorne

who remembers when tracks began broadcasting races from afar to increase

betting pools and revenue, with offtrack betting parlors opening so

gamblers no longer needed to visit tracks like Sportsman’s Park. The

Cicero venue closed in 2002, shortly after War Emblem won the Illinois

Derby there, then captured the Kentucky Derby as an improbable 20-1

longshot.

A TV screen

can’t match live racing, Fairley says, and horse racing needs fans at

tracks. While he doesn’t like simulcasts, Fairley is a fan of casinos at

tracks, which he calls a game changer. “It’s a business for us,”

Fairley says. “We need to make a living.”

Image

is to blame for part of horse racing’s woes, according to a 2011 report

commissioned by The Jockey Club. Fewer than 25 percent of the public

had a positive impression of horse racing, according to the report, and

just 46 percent of fans who attended at least three races annually said

they’d tell others to follow the sport. By contrast, 55 percent of poker

players said they’d recommend the game to friends; more than 80 percent

of football and baseball fans said they’d promote their preferred sport

to other people. Attitudes are reflected in the handle, which peaked,

nationally, in 2003.

“Racing

has a serious brand problem, a diluted product and insufficient

distribution,” McKinsey and Co., the consulting firm that authored the

study, reported.

The

2011 nationwide study, which predicted that the amount wagered on horse

racing would drop 25 percent by 2021, proved overly dire. Nationally,

the handle has stabilized at slightly less than $11 billion wagered each

year, according to a follow-up study by McKinsey that was released last

year, with the number of races dropping but purses increasing. The best

and biggest tracks have made progress, with the number of races and

wagers increasing, but those gains have been offset by trouble at

smaller venues, where handles have gone down and the number of races has

dipped. The number of horses continues to drop, the consultant reported

last year, resulting in an average field of 7.7 horses for races, not

good from the perspective of fans who want more contestants.

Myriad

issues account for the sport’s shaky health. Bettors are disheartened

by the rise of computers and near-instantaneous wagering – odds change

depending on amounts bet, and when well-financed interests from

whoknows-where throw big money at races less than a minute before post

time, what seemed a shrewd call on a longshot can suddenly become an

even-odds bet. Tracks, also, have caused consternation among the most

loyal racing fans by taking, some might say skimming, from winners who

don’t collect the full amount on successful bets. Instead, tracks take a

percentage of winning wagers to help cover overhead, a proposition that

goes over as well at a racetrack as it would at a video gambling parlor

that paid out $1.90 when the ticket says you won $2. Animal welfare,

long a concern, has mushroomed with tragedies at Santa Anita Park, a

California track where 30 horses have died since December, prompting

calls to ban racing.

The

Jockey Club says equine deaths, calculated on a per-thousand-start

basis, have declined since 2009, when the organization began publishing

racetrack death statistics. Reporting is voluntary, and while almost

every track provides numbers to allow a national perspective, most

tracks don’t allow the Jockey Club to publish statistics showing the

number of deaths at their venues. Hawthorne, which allows the club to

post statistics, stands out in the 2018 report, recording a higher death

rate of thoroughbreds – the track hosts both thoroughbred and harness

racing – than any track that voluntarily reports save Churchill Downs,

home of the Kentucky Derby.

Miller

says the track allows The Jockey Club to publish details because

transparency is important. “We understand that, if something does

happen, if there’s an injury, a death, we want to look into it, we want

to understand why and we don’t want to hide it,” he says. Thoroughbreds

go down more frequently than standardbreds, and there have been no

tragedies during the current harness racing season, Miller said. While

numbers from the Illinois Racing Board, which regulates horse racing,

show that Hawthorne has had more deaths per 1,000 starts than the

state’s other two tracks in eight of the past 11 years, Miller says

Hawthorne considers last year’s numbers an anomaly.

Death

hurts, McCaffrey says. Before becoming director of the thoroughbred

horsemen’s association, McCaffrey trained standardbreds. “You do it

because you love the animal – that’s the basis for entering into the

sport,” he says. Enzo The Baker was McCaffrey’s star. At two years old,

the horse named after a character in The Godfather never finished

out of the money in nine races, winning seven times, placing once and

showing once. It all ended in 2008 at Maywood Park, a harness track near

Chicago that closed four years ago. While warming up, Enzo The Baker

collapsed prior to a race, victim of a heart defect. “You see this

perfectly healthy horse, the next minute, he was on the ground, dead,”

McCaffrey says. “It affected me. I was never the same trainer

afterward.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].