Politicians wrestle with legal weed

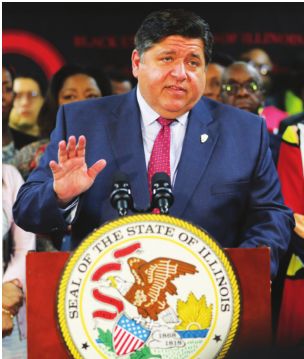

Gov. J. B. Pritzker and other backers of recreational marijuana have said that ending cannabis prohibition is about social justice, public health and reality, not just money.

Nonetheless, Pritzker’s financial goals when it comes to pot are ambitious – his draft budget included $170 million from licenses and fees during the next fiscal year. Potential tax revenue isn’t clear in a 522-page bill that addresses such granular issues as packaging -- it would be illegal to sell marijuana in a container that includes a depiction of a marijuana leaf – and hours of operation: Weed stores could be open between 6 a.m. and 10 p.m.

Upon releasing a bill Saturday, May 4, the governor’s staff promised that the Department of Revenue soon will calculate revenue projections including pot taxes that would start rolling in next January, when Pritzker wants to start legal sales. And so, with the General Assembly scheduled to adjourn on May 31, one of Pritzker’s campaign platform planks, legal recreational marijuana, was unveiled absent key financial data.

It promises to add up to a bongload of bucks, with Pritzker selling his plan based on promises to make room for minorities and sundry small-timers so that Big Cannabis doesn’t take over. But, under the governor’s bill, startups won’t be treated the same as bigtime operators with lobbyists and track records. And that has some longtime marijuana activists worried.

“We already have cannabis kingpins with the medical marijuana program,” says Dan Linn, executive director of the Illinois chapter of the National Organization to Reform Marijuana Laws. “I think this program will just create more cannabis kingpins without much room for the little guy.”

“You can’t just start a dispensary”

Legalization is popular nationwide, with 61 percent of Americans, including 76 percent of Democrats and 54 percent of Republicans, favoring legal pot in a recent Associated Press poll. Such sentiment explains why the issue is shifting from ballot boxes to state legislatures.

The first nine states to legalize pot for consenting adults did so via referendums and initiatives, with Colorado and Washington leading the way with ballot measures approved in 2012. Last year, Vermont lawmakers became the first to pass a law, absent a referendum or initiative, to legalize recreational pot. The Illinois General Assembly now stands to be the second.

In Vermont, legislators took the ultimate laissez-faire approach, legalizing pot without addressing how it should be sold or taxed, and so the state takes no cut – Vermonters now are wrestling with taxation questions. But in Illinois and elsewhere, money has gone handin-glove with legalization, with Maine and Michigan still working on plans to sell and regulate recreational pot after voters mandated legalization.

The retail recreational marijuana market in Illinois is worth between $1.7 billion and $2.6 billion annually, according

to a February study prepared by consultants hired by Democratic

legislators who back legal pot. The state would collect a 7 percent

wholesale tax and retail taxes ranging from 10 percent to 25 percent,

depending on the form of cannabis and its potency.

Under

the governor’s bill, existing medical marijuana growers and sellers

likely would have the market to themselves when sales began on Jan. 1.

In the case of dispensaries, the state would have until next May, four

months into legalization, to issue 75 new licenses, with the legislation

spelling out where stores would be located. Springfield would get one

new outlet in addition to existing dispensaries that sell medical pot in

downtown and Grandview; Chicago and surrounding communities would get

47 new shops.

The

state would have until July 1 of next year to issue new cultivation

licenses. If the state waited until the last minute before issuing them,

21 existing medical marijuana growers could have the market cornered

for a year or more, considering the time it takes to construct

facilities and grow a crop.

After

the first round of awarding new licenses, the state would have until

the end of 2021 to issue 110 additional retail and 60 cultivation

licenses. Going forward, the number of licenses would be capped at 500

dispensaries and 180 grow operations, with most of the cultivation

centers relatively small.

Under

the bill, nine large cultivation centers would be allowed, in addition

to the 21 that already exist, with each permitted to grow as many as

100,000 square feet of marijuana. The remaining 150 growing operations

each would be limited to 14,000 square feet. At full build-out and

production, the large facilities collectively would be licensed for

900,000 more square feet than the smaller facilities dubbed “craft

grows.”

Existing pot businesses would pay premiums for the first licenses to grow recreational weed.

Medical

cultivation centers that want to grow recreational weed would pay a

flat $100,000 fee, plus an additional fee of between $100,000 and

$500,000 to a state cannabis business development fund, with the amount

based on volume of medical pot sales. Existing dispensaries would pay

less, including a flat $30,000 fee, plus as much as $100,000 to the

business development fund. After that, as part of a social-equity effort

aimed at making up for years of damage from the war on drugs, both

cultivation centers and dispensaries would contribute as much as

$100,000 apiece to either cannabis industry education programs at

community colleges, the business development fund or job programs for

ex-convicts or residents of disadvantaged areas identified by the state.

Instead

of giving money to the business development fund, community colleges or

job programs, existing dispensaries and cultivation centers could

satisfy the social-equity provision by loaning at least $100,000 to a

startup pot business and providing incubation services, with the proviso

that it could have no more than 10 percent ownership in the new

entrant. And for $230,000 in fees, each existing dispensary that wants

to sell recreational pot could add a second location in time for opening

day, with geographical limits that would keep new locations with the

same areas but at least 1,500 from other cannabis shops.

The

recreational program wouldn’t affect a burgeoning medical marijuana

industry, which realized $136 million in retail sales last year and

brought in $44 million through the first three months of this year.

There are no plans to grant new licenses to grow or sell medical pot or

change existing fee structures.

While

Linn predicts windfalls for large marijuana businesses, Chris Stone,

chief executive officer of Ascend Illinois, a business created in recent

months when a Massachusetts firm purchased two dispensaries and

acquired leasing rights for a Pike County cultivation center, said

concerns about Big Cannabis gaining unfair advantages over small

operators are overblown.

Given

the state’s experience with medical marijuana, it would take about a

year for a new entrant to have cannabis ready for market once the state

issues a license, Stone says, but the period of time that established

operators have the market to themselves shouldn’t be a big deal.

“I

think people need to be a little patient,” Stone said. “I think there’s

going to be plenty of opportunities. You can’t just start up a

dispensary, you can’t just start up a grow operation.”

“The smaller person can’t afford it”

No

other state charges anywhere close to six figures for an application or

license to grow, process, transport or sell recreational marijuana, and

so Pritzker’s plan stands apart. Licenses for newcomers in Illinois

also wouldn’t come cheap.

New

cultivation centers, each limited to 14,000 square feet of growing

space, would each pay $40,000 nonrefundable application fees, plus

$100,000 upon being awarded a license. In addition to having access to

$100,000 in liquid assets, new dispensaries would

pay $5,000 nonrefundable application fees. Annual retail licenses would

cost $30,000. Pritzker's plan also establishes a processing license for

entities that turn raw cannabis into concentrates and other products,

with application fees set at $5,000 and annual licenses at $40,000.

With

annual license fees set at $30,000, Nevada is the only state with

five-figure license fees for businesses permitted to grow or sell

recreational marijuana.

Looming

high licensure costs in Illinois are part of the reason some, including

the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, oppose

legalizing recreational pot.

Teresa

Haley, president of the Illinois chapter of the NAACP, says her

organization’s opposition to recreational marijuana is mainly based on

health concerns and the potential that folks with histories of substance

abuse will be vulnerable if weed is legal. But money, she says, also is

important.

Haley said

she knows three people who together hoped to open a dispensary under

the state’s medical marijuana program but found that $800,000, the

amount they’d secured, wouldn’t be sufficient to cover licensing costs

and other startup expenses totaling more than $1 million, she recalls. A

cultivation center also would have been tough, she says. “Most black

people don’t have acres of land,” she says.

Backers

of legal weed tout jobs, but pay can be paltry. While CEOs of large

cannabis companies make six or even seven figures, trimmers who clip

leaf from buds make less than $30,000 a year, according to a recent

salary survey published by Marijuana Business magazine. Master

cultivators in charge of growing operations can earn $100,000 or more,

as can experts who know how to extract THC from raw cannabis, according

to the magazine, but bud tenders who wait on customers in dispensaries

make less than $15 per hour. “It’s OK for us to work in these places,

but we want to own them,” says Haley. “The smaller person can’t afford

it.” While the NAACP opposes recreational marijuana for reasons aside

from economics, Haley says her opposition doesn’t extend to medical

marijuana.

Lou Lang, a

former state representative who pushed medical marijuana through the

General Assembly before becoming a lobbyist, allows that the state’s

medical marijuana program hasn’t benefited minorities to the extent the

program’s creators wanted. “That didn’t work out to get us to where we

wanted to go,” he says.

Under

the governor’s bill, the Department of Commerce and Economic

Opportunity would set up a loan program to help disadvantage license

applicants with startup costs. Pritzker’s plan also would reduce license

application fees while awarding bonus points in licensing decisions to

applicants deemed to have suffered disproportionate consequences from

the criminal justice system. The list includes people who’ve been

convicted of marijuana offenses and members of their families.

After

regulatory costs are covered, 25 percent of proceeds from taxes and

other revenue generated from recreational marijuana would be deposited

in an account dubbed the Restoring Our Communities fund, a new pot of

money that would provide grants aimed at reducing violence, particularly

gun violence, and increasing economic development in communities

ravaged by violence, poverty and high incarceration rates. A board

including legislators, former inmates, experts in violence reduction,

members of community groups, officials with several state agencies and

representatives from the governor’s office and attorney general’s office

would decide how the money is spent.

In

addition to money for the new fund, 35 percent of recreational pot

revenue would go to the state general fund, 20 percent would be

allocated for substance abuse and mental health treatment, 10 percent

would go toward paying the state’s overdue bills, 8 percent would be

sent to the state Law Enforcement Standards and Training Board and 2

percent would be spent on drug education and substance abuse awareness.

Different states, different schemes

With 10 states having passed pot legalization measures, no two

regulatory schemes are the same, ad so there is no surefire template.

The

day before Pritzker announced his plan, Lang, the state

representative-turned-lobbyist for the marijuana industry, said he

agrees with state Rep. Kelly Cassidy, D-Chicago, who’s pushing legal pot

in the legislature and has been quoted as saying no state has mastered

legalization.

“I

don’t think any state has done it right, either, and I hope we do,”

says Lang, whose client list has included Chicago-based Cresco Labs,

which owns three Illinois cultivation centers and, with operations in 10

other states, is one of the nation’s largest cannabis companies. “The

point is, we have to find a happy medium.”

Linn,

who manages a Grandview dispensary in addition to heading the Illinois

chapter of NORML, says the state’s track record with medical weed hasn’t

been great. At $250 to $400 an ounce, medical marijuana costs more in

Illinois than other states, he says, and there have been shortages.

On

the plus side, Linn says, Pritzker’s plan would allow people to grow up

to five plants at home, which would act as a safeguard against high

prices. But giving an early start to

existing medical pot businesses, charging high licensing fees and

capping the number of licenses undercuts the goal of extending economic

opportunity to the disadvantaged, he says, while setting the state up

for recreational pot shortages and gouging.

“We’re

basically treating this crop like it’s plutonium or a huge vice,” Linn

says. “What we should be doing is fostering a cottage industry and not

just making this a playground for venture capitalists.”

To

help prevent companies from gaining overly large market shares, the

Pritzker plan would limit the number of licenses a single person or

business could own. But Big Cannabis has found ways around such

restrictions in other states. In Massachusetts, the state is

investigating cannabis companies that have told investors they control

as many as a dozen retail pot stores, operating under different names,

despite regulations barring ownership of more than three outlets. In

California, large growers have skirted limits on big operators by

acquiring scores of small cultivation licenses.

While

large out-of-state marijuana companies have set up in Illinois since

medical marijuana became legal, Washington state keeps the industry

local by barring nonresident ownership of pot shops or cultivation

operations. Pot business owners can get financing from sources outside

Washington state, but such financing must be approved by state

regulators.

Washington

also is notorious for low licensing fees. The application fee is $250

and an annual license to grow or sell weed costs $1,480, with each

growing license allowing operations as large as 30,000 square feet and

growers allowed as many as three licenses. With a cap of 556 retail

operations, Washington (population 7.5 million) has licensed 506

outlets, more than would be allowed under Pritzker’s proposed cap for

Illinois (population 12.74 million). After issuing more than 1,000

licenses to growers since voters approved legal pot in 2012, Washington

has stopped accepting new applications. So has Oregon, where licenses

are cheap and 664 applications were submitted in two weeks after the

state last year announced that it would soon stop issuing new permits

for marijuana businesses.

Washington

also is famous for low prices, with ounces last year retailing for as

little as $40. Taxes for recreational reefer in Washington are the

highest in the nation at 37 percent, all charged at the retail level,

with per-capita tax revenue also near the top at $42.96 for every state

resident. Colorado, which has 1,400 licensed cultivators and levies a 15

percent wholesale tax plus a 15 percent retail tax, had the highest

per-capita tax revenue of any state last year, with $46.79 in pot taxes

collected for every state resident. Washington and Colorado were the

first states to legalize recreational pot.

On

the other hand, there is California, where licenses are relatively

cheap, taxes are high and sales have been disappointing since

recreational retailers opened last year. At $8.72 per capita, California

last year ranked dead last in terms of taxes collected from

recreational pot -- unless you count Vermont, which levies no taxes on

pot sales.

“California made a mess of it,” Lang says.

“California

has thousands of dispensaries. There’s some loose regulation. It’s open

season. I don’t think the state of Illinois should succumb to that. …

The Washington model may be slightly better.”

With

the legislature scheduled to adjourn on May 31, lawmakers have less

than three weeks to pass a bill. Will it happen? Stone, who says he

participated in working groups that helped craft the current version of

the bill, says he’s not sure, but tweaks are likely.

“I

would have told you four months ago it would happen,” Stone says. “I

don’t know if I could tell you that now. You’ve got some stakeholders

that are going to be opposed to some of the provisions that are in the

bill. I know law enforcement is going to be up in arms about the home

grow.

“I’m assuming

there’s going to be negotiations between stakeholders and the

administration in the next three weeks if they really want to get

something done.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].