In Sangamon County, just three people have been charged with drug-induced homicide since Illinois passed a law in 1988 allowing criminal charges for distributing a substance that proves fatal to the person receiving it. However, the law makes no distinction between someone who is selling narcotics or provides a fellow user with what proves to be a lethal dose of a substance.

With the escalation of overdose deaths in Illinois and the state’s efforts to combat the opioid crisis, a 1989 law that has been used sparingly in the past is starting to gain momentum.

“This particular charge has become more common because of powerful synthetic opioids like fentanyl,” said Sangamon County State’s Attorney Dan Wright. “My job is to enforce the law, advance justice and ensure public safety. When there’s evidence to support drug-induced homicide beyond a reasonable doubt, I’ll prosecute.”

Drug-induced homicide is a Class X felony in Illinois and carries a sentence of up to 30 years, which is more than seconddegree murder or manslaughter. The only homicide charge with a greater potential sentence is first-degree murder.

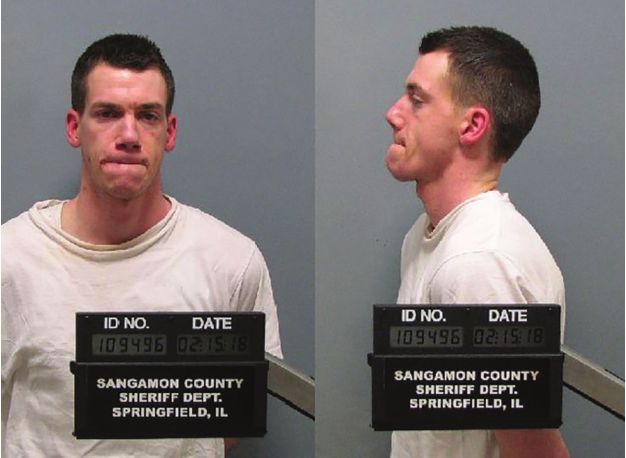

Justin Callarman was indicted on charges of drug-induced homicide on Dec. 18. He’s the most recent person in Sangamon County to be charged with the crime.

William Gerding died Sept. 3, and Callarman allegedly delivered the fatal dose of heroin and fentanyl to Gerding between Aug. 31 and Sept. 3. Callarman was arrested Dec. 13 and is currently in the Sangamon County jail awaiting his trial.

Callarman previously had numerous interactions with police, ranging from petty thefts to more serious crimes. The Sangamon County Sheriff’s Office denied freedom of information requests regarding investigation of Callarman, but police records describe Callarman as an addict spiraling out of control for over a decade.

In

one interaction with an officer from the Springfield Police Department

on Sept. 4, 2010, Callarman was found asleep in a vehicle while parked

in front of a gas station on Monroe Street. He was in the driver’s seat

with the keys resting on his lap, feet dangling from his vehicle. The

officer who spoke with Callarman that night said he smelled like alcohol

and that his pupils were consistent with someone who was high. The

officer wrote in his report that he asked Callarman to roll up his shirt

sleeves during a field sobriety test, where he observed “fresh puncture

sites or track marks” on Callarman’s arm. The officer eventually found a

syringe and spoon in one of the pockets of Callarman’s cargo pants.

Residue left in the syringe and on the spoon tested positive for heroin.

Upon learning that he was being arrested for driving under the

influence, Callarman reportedly exclaimed, “I didn’t even drink that

much. All I did was shoot some heroin two hours ago, so it’s not like I

was driving drunk.”

Those

who are addicted to opioids know they’re only hours away from

experiencing the intense, flu-like symptoms of withdrawal if they don’t

use. Many users say the potential long-term ramifications, including the

risk of arrest or even death, are pushed to the back of their minds

when the threat of withdrawal begins to loom.

Springfield

resident Brandy Klauzer is someone who understands those risks. She’s

battled addiction for over 20 years and says she’s been off heroin for

about a year.

“My love

affair with pills and opiates happened in 1999,” Klauzer said. “It went

from a few surgeries and finding Vicodin. It escalated to me going to

treatment. At one point I was eating 22 Vicodin a day.”

Once

she began using regularly, she moved out of her partner’s home because

Klauzer knew her substance use would ultimately lead to the relationship

ending. That’s when her drug use increased and she tried to earn extra

income to support her habit.

“My

habit went from $20 a day to $200 a day to me selling,” Klauzer said.

Given her increased use, she said she ended up being her best and only

customer.

While

Klauzer had never heard of druginduced homicide, by her own account, she

could have easily been a case like Justin Callarman if someone she was

using with had died.

Klauzer

said her group of friends and fellow users talked about getting clean,

but it took nearly five years before she began receiving addiction

treatment.

She

explained that the addicts she knew chose to get high in groups, so that

someone could call for help in case of an accidental overdose, because

carfentanil-laced product had made its way to Springfield. Ironically,

she and her friends sought out carfentanillaced heroin they knew to be

more dangerous because it was strong enough to keep them from going

through withdrawal.

“We have no other choice, being addicted to opiates the way that we are,” Klauzer said. “We have to use.”

Mixed signals

Millions

of dollars of federal funding has been allocated to battle the

nationwide opioid crisis, and Illinois has received its share. Earlier

this month, the Illinois Department of Human Services announced the

state had secured an additional $15 million in federal funding, for a

total of $82 million to combat opioid addiction since September 2016.

However,

the number of overdose deaths in Illinois climbed above 2,400 in 2016

and has remained consistent since then. Provisional data from the

Illinois Department of Public Health lists 2,642 overdoses in 2018.

That’s about 130 less overdoses than 2017 numbers, but a major jump from 1,579 overdose deaths in 2013.

Illinois

legislators have enacted laws that expand resources needed to support

people battling substance abuse while, at times during the same

legislative session, enacting more punitive laws for those who are

caught with drugs.

A

bill currently under consideration by lawmakers would increase sentences

for anyone caught with fentanyl. At the same time, a bill to create

more needle exchange programs and provide test strips to check for

fentanyl-laced heroin is also being considered.

Attorney

General Kwame Raoul has added Illinois to the list of more than 1,600

local and state governments that have filed suit against Purdue Pharma, a

Connecticutbased pharmaceutical company that Raoul alleges engaged in

deceptive practices and misinformed doctors about the addictive nature

of OxyContin.

Though

the attorney general’s lawsuit is primarily based on the influx of sales

representatives the company sent to Illinois to ramp up drug sales, the

lawsuit contains multiple references to the risk of addiction

associated with the company’s branded drug and the outcome from pushing

OxyContin, which company reps touted as a “safer” alternative than other

pain medications.

“There

are no reliable clinical studies supporting the use of opioids long

term; however, there exists a wealth of evidence establishing that

opioids are both addictive and deadly,” the lawsuit states.

Earlier

this year, 23 state representatives signed a resolution to urge the

Department of Public Health to revisit its painkiller prescription

guidelines.

David

Vail, a substance abuse counselor at Clinical Counseling Group in

Springfield, said the vast majority of people can use drugs

recreationally without issue, but approximately 10% to 14% of users are

prone to addiction. He explained there’s also a difference between

addiction and being physically dependent on substances like opioids.

“Addiction

occurs in the brain … we have enough studies, we don’t need to spend

another dime on addiction studies,” Vail said. “We need to spend money

on what it looks like with long-term recovery and short-term recovery

and how we can get people well.”

The

underlying cause of addiction, he said, is unaddressed trauma that

manifests in behavior. Vail said childhood trauma and use of substances

before the age of 19 are common denominators among the segment of the

population that’s most vulnerable to abusing drugs. He said the majority

of IV drug users have been subjected to some type of abuse.

“We

just know more about traumainformed care because of the brain research

than we’ve ever known before,” Vail said. “These things will dictate

life trajectories and there’s just no way to avoid it.”

Vail

said taking a top-down approach at the state level to better provide

substance users resources to kick their habit while simultaneously

enacting punitive laws won’t resolve the current opioid crisis or

addiction in general.

He said the best way to address addiction

is long-term care that treats those in recovery with compassion. He

noted that threatening addicts with punishment isn’t a strong enough

deterrent.

“Condone it

or not, [drug use] is going to happen,” Vail said. “Either you want to

help with the problem with the level of care we give people, or you’re

going to bury your head in the sand.”

Illinois

passed the Good Samaritan Act in 2011, granting limited immunity for

those who seek medical attention for someone overdosing. However, the

law doesn’t extend immunity when those seeking medical attention are in

possession of more than three grams of heroin or morphine or 40 grams of

prescription pills. It also doesn’t apply if the person overdosing dies

and the person who sought help provided the drug.

Deadly habits

Illinois

prosecutors indicted 486 people on drug-induced homicide charges

between 2011 and 2016, according to data from Drug Policy Alliance, an

organization interested in reforming drug policies. Prosecutors from the

four most populated states – California, Texas, Florida and New York –

collectively charged 399 people during that same period.

The

Sangamon County state’s attorney noted that the statutory language

regarding drug-induced homicide is not limited only to people selling

narcotics.

“The charge

does not require it be a purchase or a sale of a controlled substance,”

Wright said. “It states the charge was appropriate if there’s an

unlawful delivery. We view every case based on the specific evidence

presented to us by the investigation conducted through law enforcement.”

Gary

“Rob” Clark was recently released from prison after serving

four-and-ahalf years. In 2014, he became the most recent person in

Sangamon County to be convicted of drug-induced homicide.

“I

had a good life before my addiction,” Clark said. “I’m an honorably

discharged Army veteran. I was in the 173rd Airborne Brigade, but I

ruptured my spine overseas and became addicted [to painkillers]. When I

came back, I was just hooked.”

Clark

said the experience has changed him, and he’s tried to make amends to

the family of Daniel Buehrle, the man who died after obtaining heroin

from Clark.

“I had no

clue that such a charge existed,” Clark said. “The fact that it’s called

drug-induced homicide – homicide sounds like murder. It sounds like you

meant to do this, when in reality it was just three or four people

together trying to feed an addiction. It’s the most harsh wording for

the most unfortunate scenario.”

Springfield

Police Department reports about Buehrle’s death in October 2012 include

an interview with a man who called for assistance once Buehrle

overdosed in the parking lot of Southwind Park. The man told police he

tried to move Buehrle in an attempt to drive him to get medical

assistance before running off because he was “freaked out.” He then told

police he was the one who bought heroin from Clark before meeting with

Beuhrle. The same SPD report also connected Clark to an August 2012

overdose of a different individual and the death of a 25-year-old

Chatham man who died at Clark’s residence in December 2010.

During

the incident at Southwind Park, Clark said he was there with Buehrle

and tried to give him an overdose resuscitation drug, but he didn’t know

how to administer it.

“They leave that part of the story out,” Clark said.

Police reports make no mention of Clark being present at Southwind Park when Beuhrle overdosed.

Clark

was arrested in February 2013 for his connection to Buehrle’s death and

on charges of manufacturing and delivering a controlled substance.

Following Buehrle’s death, Clark had unknowingly sold heroin to an

undercover SPD officer. By all indications, Clark was selling small

quantities of heroin to support his own habit.

Like

most people who have struggled with addiction, Clark tried to get clean

several times before his conviction. He said he drove to Champaign and

Decatur on a few occasions to check into a detox center because there

was a lack of options available in Springfield.

His attempts at staying clean failed.

Heroin

transported from St. Louis and Chicago, with Springfield flooded with

the drug along the way, and life in general, made sobriety difficult.

“It’s

almost impossible to do it on your own, and now I see that,” Clark

said. “I tried to do it, and kept failing, because I didn’t understand.”

Clark

said he’s looking forward to the life he missed during the height of

his addiction. He said the only good thing to come out of his time in

prison was gaining his sobriety, but he still thinks the term

“drug-induced homicide” is a misnomer that makes those convicted seem

like they’re violent offenders. He insists that’s not the case.

Clark

said he and Callarman were familiar with one another since they both

grew up in Chatham, although Clark said they didn’t share the same group

of friends. Clark says he can imagine what Callarman is going through,

probably believing his life is over.

“I

met a few people in prison with the same charge.” Clark said. “None of

us were dealers. We were addicts who were using with other addicts, and

another addict died while we were with them.”