A century on, Vachel Lindsay’s Golden Book is more prescription than prediction

In 1920, the Macmillan Company of New York City published The Golden Book of Springfield written by Springfield resident Vachel Lindsay. Like everything Lindsay did, the novel was a passion project, an elaborate combination of mystical fantasy and social comment written gradually over the course of several years, always while sitting alone in Washington Park. The book, completed in 1918, audaciously depicts Springfield as Lindsay imagined it 100 years in the future, in what he termed the “mystic year” of 2018. Now that Springfield has reached the time of Lindsay’s imagining – coinciding with Illinois’ bicentennial – the Vachel Lindsay Association and the city are preparing several events commemorating, celebrating and reevaluating Lindsay’s legacy.

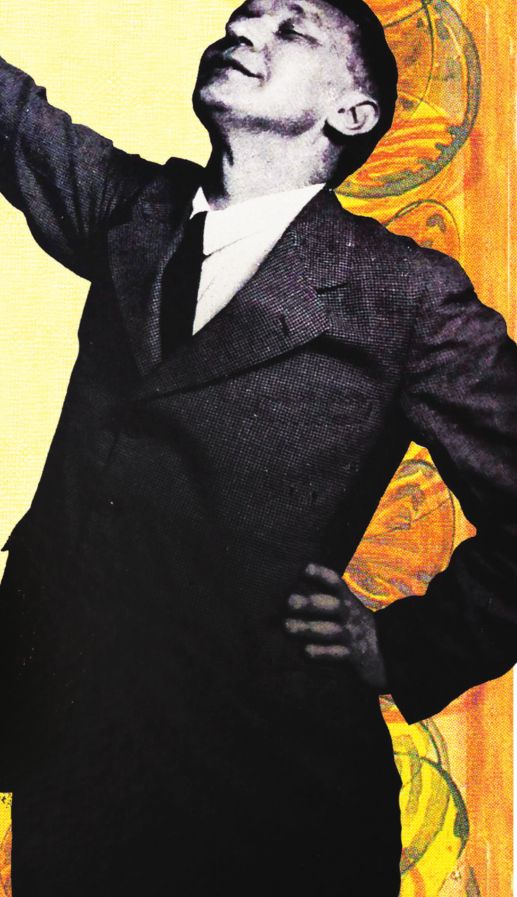

At the time of The Golden Book of Springfield‘s publication, Lindsay was a celebrity, one of the most well-known poets in the country. Famous for his explosive, theatrical live performances of poems like “The Congo,” Lindsay was known as a wild man of literature, flailing his arms and foaming at the mouth during readings of poems that were written to be heard, not read. In many ways, Lindsay’s flamboyance can make him seem in retrospect like more of a proto-rock ’n’ roller (as well as a precursor to the Beat poets and performance artists of the last half of the 20 th century) than the cliché image of a deskbound, academic, literary type. Lindsay was also passionately committed to social justice, writing and distributing pamphlets and walking across the country multiple times to spread his views on

issues such as racial equality, protofeminism (“America… should have one

patriotism, one caste rule, one religion, the religion of honoring

woman as a comrade citizen”) and socialism. Ironically, over the years

his work has frequently been criticized and dismissed as insensitive,

sexist and even racist.

The Golden Book’s storyline,

such as it is, begins in 1918, with a fictional Vachel Lindsay stand-in

joining a small group of Springfieldians calling themselves “The

Prognosticators Club” in gathering around a table, séancestyle, and

projecting themselves forward to “mystic year” 2018. They are visited by

the literal Golden Book of Springfield, a quasipsychedelic entity whose

dramatic entrance is described thusly: “a book of air, gleaming with

spiritual gold, comes flying in through the walls as though they were

but shadows. It is a book open as it soars, and every

fluttering page is richly bordered and illuminated. It has wings of

black, and above them wings of azure. Long feathers radiate from the

whirring, soaring pennons.” Once successfully projected into 2018,

Lindsay wanders the streets, hanging out at the corner of Fifth and

Monroe, “loafing” around in coffee shops and befriending the future

residents of his hometown, forging a special connection with the book’s

heroine, socialite-warrior-goddess Avanel Boone, a direct descendent of

Daniel Boone, eventually witnessing a climactic aerial battle for the

soul of his hometown. The frequent refrain of “Springfield awake,

Springfield aflame!” is used throughout the book as a sort of

fist-pumping affirmation of Lindsay’s utopian hopes for the city he

loved.

“The Golden Book represents

his entire life boiled down into one book,” said Springfieldbased poet

and Lindsay scholar Ian Winterbauer, who often hosts tours of the Vachel

Lindsay House at 603 S. Fifth St., where Lindsay grew up and lived as

an adult, now a museum and historic landmark. The Golden Book was

published two years later than Lindsay had wanted and received poor

reviews from American critics. Like many innovative U.S. artists

throughout the years, Lindsay was better appreciated during his lifetime

by European audiences and reviewers than in his own country. “He was a

people’s poet,” said Winterbauer. “People at parties liked him a lot,

but other poets tended not to. Lindsay’s work may have started in

classrooms – he attended the Art Institute of Chicago and the

Metropolitan Museum of Art – but his audience ended up being the people

on the streets.”

Some

dated word choices and other historical considerations can make Lindsay

a difficult read for some contemporary audiences, but far from being

racist or sexist, Lindsay’s work in The Golden Book tends to

venerate its black and female characters to the point of

near-idealization. “I think most people now who might try to read this

book will see the word ‘negress’ and immediately tune out,” said

Winterbauer. “It’s important to remember that this was 1918 and the term

‘African-American’ did not exist. Second of all, the ‘negress’

character is a strong, independent hero. Every female character in The Golden Book is strong and independent and a heroic figure.”

Lindsay’s

enlightened (for 1918) attitude toward minorities was informed by

growing up in what was then a largely black area of Springfield. In

fact, he and his father, a doctor, witnessed the beginning of the race

riot of 1908 from their window facing Fifth Street. “More than 40

businesses were burned downtown because they were run by nonwhite

people,” said Winterbauer. “The crowd then stormed through the

Governor’s Mansion lawn [directly across from the Lindsay’s home] to

head to where Boone’s Saloon is now, where they lynched and slit a man’s

throat in front of his family because he was black and his wife was

white.” The victim, an elderly cobbler named William Donnegan, had made

shoes for Abraham Lincoln during the future president’s time in

Springfield. After witnessing the riot, Dr. Lindsay – who had been

raised by his own father’s slaves and had already been providing

affordable housing to black tenants in the building behind the Lindsays’

residence – began treating nonwhite patients secretly, during the night

and for no charge, from the porch of his home, at considerable risk to

his career and reputation.

Also

shaken by witnessing the riot, Vachel Lindsay later wrote and spoke

extensively about the need for racial equality in America, and during

his cross country “tramps,” he regularly debated fellow citizens on the

subject, particularly in the South. One of Lindsay’s crowning

achievements, according to Winterbauer, was the time he stayed on a

Florida plantation, the owner of which was an old and sick former slave

owner, whom he debated for hours on the subject of race. “The guy could

have shot Vachel in the head and dumped him in the swamp and nobody

would have ever heard from him again,” Winterbauer pointed out, “but

Vachel challenged that guy and by the time he left, the guy admitted

that maybe black people do have souls but they’re just smaller than a

white person’s.” Lindsay chalked this up as a victory because he had

gotten an inveterate racist to change from seeing black people as

objects to seeing them as human – if still inferior – beings. Baby

steps.

Much of

Lindsay’s audience in Springfield consisted of rich people at fancy

parties who would not have tolerated what Vachel was trying to say had

they understood it, according to Winterbauer. “He was a novelty to a lot

of people, kind of like The Elephant Man was in Victorian England, but

Vachel legitimately did have things to say – and that is what led to his

depression, ultimately: people weren’t listening.” Lindsay lampooned

right-wing types in The Golden Book in the form of a character

named John Fletcher who is described as believing that “politics is

business and business is politics and the only worthwhile citizens are

those that ‘get the money,’” a sentiment which might not seem unfamiliar

to inhabitants of Springfield in 2018. Indeed, many of the slogans that

appear throughout Lindsay’s work are arguably as applicable today as they

were 100 years ago, including “A crude administration is damned

already,” “A bad designer is to that extent a bad citizen,” and “Without

an eager public all teaching is in vain.”

Of course, not all of Lindsay’s specific predictions about his home city in The Golden Book of Springfield came

to pass. For instance, while there has been no “World’s Fair of the

University of Springfield,” the Springfield Art Association does still

operate out of Edwards Place. Elsewhere, Lindsay inaccurately predicts a

clean-shaven trend for the men of 2018 but his pronouncement that in

2018 “everywhere south of Mason and Dixon’s line they say that Grant

surrendered to Lee. It is in every Southern schoolbook,” has a certain

ring of truth to it, at least in spirit. The mayor of Springfield in The Golden Book’s version

of 2018 is a Boss Tweed-style caricature named “Slick Slack Kopensky,”

bearing little resemblance to our Mr. Langfelder. Segregation and racism

are presumed to have remained at 1918 levels in “New Springfield,”

which is thankfully not the case, but Springfield’s women of the “mystic

year” are in the workforce and described as voting in larger numbers

than men. At the same time, Lindsay’s pronouncement that “having a

private fortune is proclaimed in every political speech to be against

the Constitution” seems fairly far-fetched in the billionairedrenched

political landscape of actual 2018, as does the prediction that in 2018

“saloons are as extinct as the trilobite.”

Perhaps

most striking, Lindsay’s description of “an extraordinary,

world-conquering device, some amorphous, dubious toy, akin to the

ancient phonograph” can’t help but conjure up a dim foretelling of the

smartphone. And his attendant concerns (“Will the millennial future be a

tin and wire world, an electrical experiment station and no more?”)

seem worth bearing in mind.

Lindsay’s

most important idea, according to Winterbauer, was that of “the new

localism” – an early version of the currently popular idea of thinking

globally and acting locally. “If you know how to make your community

better, go out and apply it – if the entire world is focusing on its

communities, producing its own food, ensuring that there aren’t race

riots in the street, then the world will be better,” said Winterbauer.

“I think Vachel would want people now to ask themselves, what am I doing

to make the world a better place and who am I actually doing it for?”

Scott Faingold can be reached at [email protected].