Tax collectors in the Bible

occupy the same social strata as sinners and prostitutes. The Beatles

portrayed the taxman as a taunting, greedy parasite.

Tax collectors in the Bible

occupy the same social strata as sinners and prostitutes. The Beatles

portrayed the taxman as a taunting, greedy parasite.

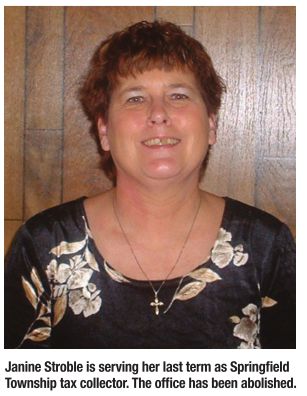

And

then there’s Janine Stroble. For 32 years, Stroble has been the tax

collector in Springfield Township, home to 6,234 people who live in an

area that stretches from Grandview to the outskirts of Abraham Lincoln

Capital Airport. She makes house calls, visiting elderly and disabled

folks to pick up property tax payments each spring, when the township

handles tax bills. Come fall, when Sangamon County does the collecting,

Stroble makes deliveries, stopping by homes of folks to pick up checks

and convey them to the county treasurer.

She

is hardly unpopular, having occupied the elected position of tax

collector since 1985. The township’s tax collection season is as much a

social event as a time to render unto Caesar.

“These

people coming into this office when collection time comes, they’ll sit

down with her and talk for half an hour or 45 minutes,” says Gary Budd,

township supervisor. “They love that personal touch.”

“Sometimes

we have to boot them out because other people are coming in,” Stroble

says. They tend to be older than 50, and they like paper receipts.

Stroble,

who earns $7,100 per year, says that she collected $1,049,114.85 this

year from between 300 and 400 taxpayers who came to her instead of

pointing and clicking or relying on the post office. Strictly speaking,

it’s a completely unnecessary service, given that property owners can

pay by mail or pay online or go to the courthouse if they insist on

paying in person. And the overwhelming number of taxpayers, or banks

that hold mortgages, do exactly that. Of the $350 million or so that’s

paid in property taxes each year in Sangamon County, no more than 8

percent flows through the county’s 26 townships instead of the county

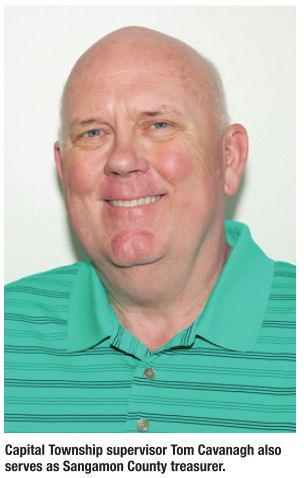

treasurer’s office, says county treasurer Tom Cavanagh.

Stroble’s

days as a tax collector are numbered, thanks to the state legislature

and Gov. Bruce Rauner, who last spring signed a bill to eliminate

tax collectors in Sangamon County. Last November, 75 percent of Sangamon

County voters favored eliminating tax collectors in townships where

they still exist – at least nine townships in the county already have

done away with the job. But paring down government can be a slow

whittle. The county citizens efficiency commission in 2014 recommended

that collectors be eliminated, but that won’t happen, even with the new

state law, until 2022, when terms for collectors expire.

It

is, at least, a start for critics of townships who have long argued

that the state’s 1,432 townships are largely, if not completely,

unnecessary, a throwback to an agrarian era when cities were small, far

from each other and phones not yet invented. Seventeen counties in

Illinois manage without any townships within their borders. Chicago

hasn’t had townships since 1902. Cities and counties elsewhere now

perform services once accomplished by townships, and some townships have

seen coffers overflow to the point that the state has established a cap

on how much money can pile up.

The

new law capping fund balances isn’t the only measure the state has to

restrict townships. The governor last month signed a bill that allows

voters to eliminate townships that are wholly within cities and merge

and consolidate townships in unincorporated areas. The governor also

approved a law allowing voters to abolish township road districts, which

have taxing authority distinct from whole townships. Rauner also signed

a bill to abolish any township road district that doesn’t maintain at

least four miles of roadway.

It

has not, in short, been a good year for lovers of townships. Budd, the

Springfield Township supervisor, is pessimistic about the long term.

Fifty years from now, he says, his township may not exist, largely

thanks to the growth of incorporated areas.

“We

have a lot of cities, they’re going outside their boundaries and

circling us,” he says. “They’re starting to surround us.” But Budd says

he’ll never give up.

“I believe in township government,” Budd says. “The way people are

putting this out, it sounds like there’s a lot of duplication. But you

can’t duplicate the personal touch. I’m going to fight this until the

cows come home.”

Bursting coffers

Townships in Illinois never have won universal acclaim. Consider the take of the Illinois Journal in 1849, when a new state constitution allowed for the creation of townships by popular vote.

Prior to a public vote, the

Springfield newspaper published a primer on the new form of government,

explaining the basics. The township would employ a supervisor, an

overseer of the poor, constables, an assessor, highway commissioners and

as many poundmasters (an old-fashioned term for folks tasked with

confining stray animals) as needed. Anyone elected to a township office

who refused to serve would be fined $25, save for recalcitrant

pound-masters and overseers of the poor, whose fines for refusal to

serve were set at $10. Noting that state enabling legislation setting

the rules for townships ran to 34 pages, the paper near the end of a

lengthy front-page article gave up trying to explain the finer points.

“We

have only reached the ninth section (of the law),” the author wrote.

“Persons wishing to make themselves fully acquainted with this matter

had better examine the law at length. Our own opinion is that counties

hereabouts are not in a situation to adopt this new system.”

Nonetheless,

townships soon became common throughout Illinois, ushered into being

with the promise of hyper-local government that would be more responsive

to the wishes of constituents than distant officeholders in faraway

county seats or the state capital. It never has been a perfect system.

In

1878, the Sangamon County board of supervisors, thanks to an enabling

law from the legislature, created Capital Township, with borders

matching the city limits of Springfield. The rationale was fairness.

Three-quarters of the taxes paid by Springfield Township residents came

from property within the city, but residents from outside the city

controlled how the money was spent, proponents of the new township said.

City residents, creators of Capital Township decreed, should decide how

to spend money from taxes generated by property within city limits.

Nearly

140 years later, the township could face a reckoning, thanks to a new

state law that allows voters in Capital Township and 16 other of the

townships in Illinois that are wholly within cities to abolish

townships. Under the law that takes effect in January, voters could

abolish such townships if both city councils and township boards agree

to put referendums on the ballot. While townships in rural areas are

responsible for maintaining roads, townships that share borders with

cities with street departments have few duties.

Since

2014, Evanston and Belleville have eliminated townships wholly within

municipalities. In Belleville, where township trustees in 2016 voted to

dissolve the township effective last spring, the township had few duties

other than dispensing money to the poor. With more than $500,000 in

revenue, less than $203,000 was spent on welfare and social programs

last year while nearly $285,000 went for administrative and overhead

costs. For years, the township, which had 10 employees, took in more

than it spent. By the end of fiscal year 2016, more than $850,000 had

accumulated in township bank accounts, enough to run the township for

nearly two years.

Belleville

wasn’t alone in socking away money. Capital Township, where the owner

of a $150,000 home pays $44 a year to the township in property taxes,

had a fund balance of more than $2.1 million at the end of fiscal year

2016, when the township took in more than $2.3 million and spent

slightly more than $2.2 million.

Cavanagh,

the county treasurer who is also township supervisor, points out that

township taxes have been reduced – 10 years ago, the owner of a $150,000

home paid $51 a year to the township. Cavanagh doesn’t see a problem

with having nearly as much money in the bank as the township spends in a

year.

“We’ve always

thought it was prudent to have about that amount of money on hand,”

Cavanagh said. “We would not let our fund balance grow to an

inappropriate level. I believe our auditors have said it’s reasonable.”

But

60 miles southeast of Shelbyville, overflowing coffers have helped

prompt an overhaul of the Shelbyville Township board as well as a change

in state law.

Over

the years, Shelbyville Township, which collects more than $530,000 in

taxes each year, accumulated nearly $1.4 million in fund balances as of

the end of its fiscal year in 2016, according to Illinois comptroller

records. With so much money on hand and few ways to spend it (the

township, which has 13 employees, spent $163,370 on roads, $18,570 on

social services and $187,557 on administration in 2016), the township

board became generous in ways not envisioned when townships were created

in the 19 th century.

Shelbyville

Township in recent years has given money, including cash from the road

fund, to the American Legion, the local chamber of commerce, the Boy

Scouts, youth athletic groups, a charity aimed at combating cystic

fibrosis and a local meat shop that put together food baskets for the

disadvantaged. The township helped pay for a post-prom party aimed at

keeping high school students out of trouble. Shop With A Cop, a program

that sends at-risk kids on Christmas shopping sprees with officers, got a

$1,000 check. As much as $29,300 was donated to causes deemed worthy by

the township in a single year, according to township financial records

and Edgar County Watchdogs, a government watchdog group that blew the

whistle.

Lawmakers

took notice. In early September, Gov. Rauner signed a bill limiting the

amount of money that townships can accumulate in funds (with capital

funds

excluded). It is, to be sure, a generous limit. Under the new law,

townships cannot accumulate in any given fund more than two-and-a-half

times the average annual expenditure over the previous three years. In

Shelbyville, some township funds have 50 times the amount that’s

typically spent in a year, says state Rep. Brad Halbrook, R-Shelbyville,

whose wife became a township trustee earlier this year after a board of

Democrats was voted out.

The

move to cap fund balances was bipartisan, with state Rep. Carol Ammons,

D-Urbana, cosponsoring the bill with Halbrook, who figures that

Shelbyville Township has squirreled away about 10 times the amount of

money that it needs. A 1969 state Supreme Court decision already

established caps on how much money government can accumulate, Halbrook

says, but now that there’s a law, folks are paying attention.

Mike

Holland, who was named Shelbyville Township supervisor in July, says

that the township may send checks to taxpayers to comply with the

statutory limit on fund balances. “We’re going to be in a situation

where, yes, we’re probably going to have to do some rebates,” Holland

says. “Honestly, without going back and looking at financial reports, I

don’t know the total. There are some accounts that are way over.”

Making

charitable contributions with township funds wasn’t right, Holland

says, but it also wasn’t nefarious. Former township officials simply

didn’t know the law, he explains. “What those folks were doing, in their

mind, was OK,” Holland says. “There was girls softball. There was boys

baseball. Food baskets for folks who didn’t have much at Christmas time.

That all sounds wonderful, except that it wasn’t legal. … We’re going

to learn the law. We’re going to try to do it the way it’s supposed to

be done.”

Urban vs. rural

Along with maintaining roads and providing for the poor, townships are tasked with assessing property.

In

Springfield, which has the same borders as Capital Township, the job of

assessing property is statutorily intertwined with county government.

The Sangamon County treasurer is also the township supervisor and tax

collector, thanks to state law, while the county clerk is also the

township’s assessor.

“(Sangamon

County clerk) Don Gray and I are unique, inasmuch as we are township

officials, based on our elected county status,” says Cavanagh, the

county treasurer. “We’re the only ones like that in Illinois.”

State

Rep. Tim Butler, R-Springfield, who sponsored the bill that eliminates

township tax collectors in Sangamon County, says that townships in rural

areas are fundamentally different than townships in cities. Beyond

keeping roads paved and plowed, rural townships supply accountability,

he says, and it’s easy to complain if jobs don’t get done. “Folks in

rural areas have a different view than in urban areas,” Butler says. “In

a lot of rural areas, township government is your lowest common

denominator, in a way. You can’t call your alderman.”

Jim

Donelan, a Springfield alderman who is executive director of the

Township Officials of Illinois Risk Management Association that provides

insurance to townships, defends both urban and rural townships.

Donelan, who sat on the citizens efficiency commission that recommended

the elimination of township tax collectors in Sangamon County, allows

that fund balances in some townships may appear high, but that can be a

function of townships saving up to buy equipment. In Sangamon County,

Donelan says, townships are responsible for maintaining 1,100 miles of

roadway while the county takes care of 254 miles of road, and the average township road commissioner is paid $29,000 per year.

“We

(the citizens efficiency commission) had a dialogue with the county

engineer, who basically said, ‘We cannot handle the responsibility of

1,100 miles of roadway,’” Donelan says. “We found that townships are

doing a pretty darn good job with a little bit of money.”

Counties

aren’t clamoring to take responsibility for rural roads, Cavanagh says.

While township tax collectors aren’t needed, assessors are another

thing, he said. Someone, after all, needs to figure out what property is

worth, he notes.

“A lot of people have

positions on township government,” Cavanagh said. “In a lot of cases,

they don’t go very deep below the surface and realize that these are

indispensable services that have to be performed.”

Still,

there remains an urge to eliminate or consolidate townships, with

lawmakers and government reform advocates questioning the need for

townships that share borders with cities (better known in government

circles as “coterminous” townships). “I think coterminous townships,

especially, are something we need to take a hard look at,” Butler says.

“The idea that the county can provide a lot of the same services that

Capital Township provides is a good idea to talk about.”

For

practical purposes, the county and township already have morphed into

one entity, says Brian McFadden, county administrator, given that

assessments are done by the county clerk, the county treasurer is the

township supervisor and payroll and other human resources tasks for the

township are handled by the county.

“From

my viewpoint, Capital Township and the county are already merged, just

unofficially,” McFadden says. “We’ve walked down the aisle. I don’t know

if we’ve said ‘I do’ in front of the priest yet. … Everything that a

township does, the county does as well.”

While

the county administers programs that help folks with heating costs and

weatherization expenses, it does not provide help to the poor on the

scale of Capital Township, which last year provided slightly more than

$1 million in assistance to folks who had no other place to turn. Last

year, nearly 46 percent of the township’s expenditures went for welfare,

often on behalf of folks who didn’t have money for rent or utilities –

the township writes checks directly to landlords and utility companies.

It is not, the township says, an automatic handout.

“A

lot of our work is vetting,” says Kathe Pierce, director of the

township’s general assistance program. “We’re here to help as long as

you meet our guidelines. Sometimes, we’re not dealing with honest

people. They’re desperate. I don’t want to say they’re making up

stories, but they’re leaving out information that’s important to us. I

would love to be able to believe everybody who walks through the door.

Unfortunately, the track record says we can’t do that.”

Assistance

for food has been curtailed in recent years as the township determined

that the poor can get nourishment from food banks and food pantries. The

township has also phased out payments for dental and medical care

because would-be clients qualify for Medicaid. But people who aren’t

able to work can get checks intended as bridges while waiting for Social

Security benefits to be approved. They’re required to repay the

township if they receive backdated benefits.

Able-bodied

folks get paid minimum wage to work 70 hours a month for such entities

as St. John’s Breadline, the Computer Banc and Habitat for Humanity, and

they must also look for jobs. It works out to as much as $577.50 per

month, with a cap of nine months of township-sponsored workfare. If you

get fired, you’re barred from the program for four years. Otherwise, you

must wait two years between stints on workfare.

“There

are limits,” Pierce says. People can receive financial help once every

two years and five times in a lifetime, but no one has reached the

lifetime limit of five grants for utilities or rent assistance.

The

difference between the township and other welfare programs, Pierce

says, is accessibility. Someone who needs help can walk into township

offices on South 11 th Street any day except weekends and Wednesdays and

talk to a live person without making an appointment. After filling out

an application, a person can get help within a week or so.

“We

have constant communication with the clients,” Pierce says. “They can

walk through our door, and we see them that day. We don’t have a ton of

red tape. (State) public aid is overwhelmed. The clients go in there and

they may have to wait two hours to see a caseworker. We’re getting them

in the door and taking care of them efficiently. We’re always here, and

our door’s always open.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].