Faded gem needs direction

Downtown Springfield lacks many things.

A hardware store. A movie theater. A college.

A dry cleaning shop. Modern parking meters.

What it does have are things that no city wants in its urban heart. Vacant buildings. Homeless people. Empty parking lots. Railroad tracks.

Take a drive or stroll through downtown and the conclusion hammered home by “Space Available” signs is inescapable. Downtown may or may not be dying, but it is certainly not thriving.

There are bright spots. Maldaner’s and Augie’s Front Burner serve, arguably, the best food in the city. Prairie Archives is an OMG-look-at-this treasure trove for anyone interested in books and the flotsam and jetsam of Illinois history. The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum is a national attraction. The farmers market is a place to see and be seen and chat as much as it is a place to buy vegetables and bread and cheese. Obed and Isaac’s proved that Springfield residents love artisanal beer as much as Bud Light. And every town should have a Recycled Records, which takes a back seat to no one when it comes to funk appeal.

“I think it’s getting better,” says Mark Kessler, Recycled Records owner. Kessler says that he’s encouraged by a recent influx of new shops. Downtown Springfield, Inc., counts 18 businesses that set up shop in 2016.

Still, those who love downtown say they wish things could be better, and there’s palpable frustration from lack of a clear path to a better tomorrow.

“I think that progress has been made, but we need to jump-start it somehow,” says Ward 5 Ald. Andrew Proctor, whose ward includes part of downtown.

Visions and plans Like others, Lisa Clemmons Stott, executive director of Downtown Springfield, Inc., brims with ideas. Downtown, she says, would be a great place for a bowling alley, a rooftop restaurant and a movie theater. She praises recent arrivals that include a sushi joint and a yoga studio. But something big, she acknowledges, is missing, and it’s neither a business nor a building.

“We’ve got a vision problem,” Clemmons Stott says. “We don’t have this collective understanding of what the neighborhood wants to be.”

Scant leadership has come from city hall, which has a history of trying this and trying that but rarely, if ever, coming up with a plan for downtown and sticking to it.

Ward 2 Ald. Herman Senor, who represents southern portions of downtown, says the city needs a planner, an idea that’s been rejected by the mayor. Downtown and the entire city, he says, would benefit from a plan that includes proposals that could be checked off, one by one, as they’re accomplished.

Consider two acres north of the governor’s mansion that the city bought in 2014 with more than $1.5 million in money from the city’s tax increment financing fund set up in 1981. There were no other prospective buyers, and no wonder. The property includes the crumbling YWCA building and sits amid buildings with plenty of vacant space. Former Mayor Mike Houston called it “a prime block for development” and “the best property in the city” in convincing the city council to buy the site from the state.

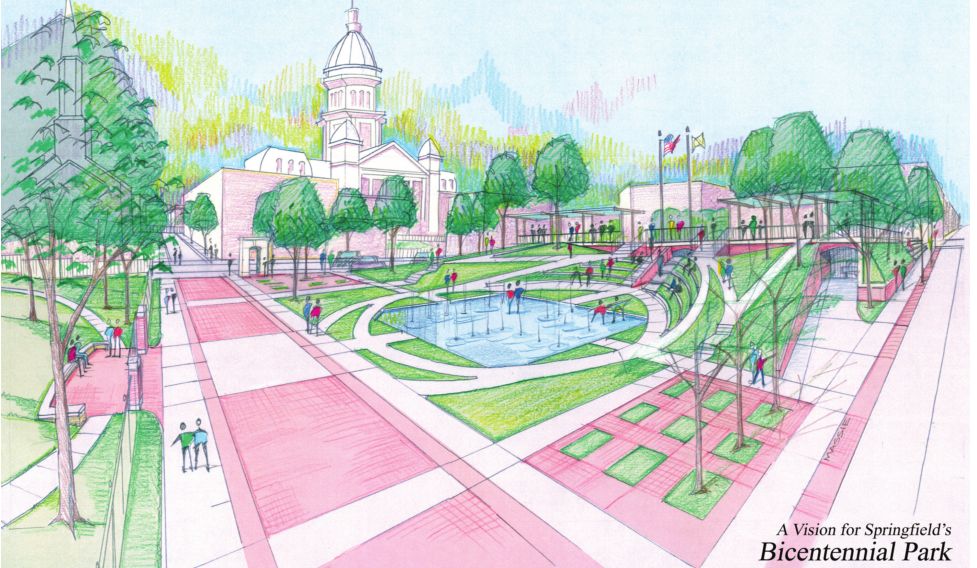

During the 2015 mayoral campaign, neither Mayor Jim Langfelder nor his opponent said just what the city should do with the property formerly known as the YWCA block, now dubbed the North Mansion Block because it sounds more gentrified. Langfelder still doesn’t appear to know what to do. When the mayor pushed to hire a consultant to come up with development proposals, he professed surprise when the consultant said that developing the site would cost at least $30 million (“Sticker shock,” Dec. 17, 2015). There is now growing consensus to create a park.

“Was that a proper use of TIF funds?” Senor says. “Looking at the end result, I don’t think you can say that. We need to not make that mistake again.”

Whether a park is a good or bad idea isn’t necessarily the point. Rather, the decision to spend seven figures on land without a plan for using it underscores the city’s piecemeal approach to resurrecting a once-proud urban core. A look at how the city has spent $73 million in tax increment financing money in downtown since the TIF district was established in 1981 shows that a haphazard approach isn’t new.

TIF spending Under state law, TIF money is supposed to help revitalize blighted areas and make possible projects that otherwise wouldn’t be done. The goal is to increase the tax base so that tax revenue generated by new development will, eventually, make up for the public subsidy on the front end. It’s hard to argue that the ALPLM, Near North Village, Lincoln Square Apartments and County Market, all of which were built with the help of TIF money, haven’t drawn people downtown and increased the tax base.

But

the city has also used TIF money to fund projects that would likely be

done no matter what, or that have questionable worth when it comes to

revitalization. A homeless shelter might be a worthy thing, but it’s

hard to see how it would revitalize downtown. Nonetheless, the city in

2011 gave the Salvation Army $1.8 million in downtown TIF money to help

build a homeless shelter that morphed into a community center that now

is being planned for the east side, outside downtown. In 2010, the city

gave $1.9 million to Horace Mann Educators Corp. to renovate its

headquarters even though the company posted a profit of nearly $81

million that year. In 2012, the owners of the PNC Bank building, which

houses one of the city’s biggest law firms in addition to a bank,

received $1.25 million for building repairs. TIF money has also paid for

carpeting in the city library, HVAC work on city hall, repairs to a

bridge that serves as a walkway between the east and west buildings that

comprise city hall, surveillance camera equipment and the services of a

bird repellent expert to get rid of pigeons and starlings using a

purportedly secret method that looked a lot like poison and firearms.

Kessler

of Recycled Records recalls getting basement fire sprinklers and an

electric disabledaccessible door in 2009, when former mayor Timothy

Davlin was in office. The city cut checks totaling nearly $50,000.

Kessler said he didn’t know that he needed the improvements until a city

inspector paid a visit.

“I met with Davlin,” Kessler remembers.

“He

said, ‘The bad news is, you have to do this. The good news is, TIF will

pay for it.’” On the other hand, Larry Quenette says that he wouldn’t

have been able to convert a vacant building on Adams Street into

apartments and office space without $1.2 million in TIF money he

received in 2010, under the Davlin administration. All 12 apartments are

rented and generating sufficient income for the project to make money,

but Quenette is still trying to find tenants for street-level offices

four years after rehab work was completed. There is simply too much

vacant office space downtown, Quenette says, and he can’t compete with

landlords willing to rent for next to nothing.

“I

would like to be a lot more successful by having all of my office space

leased up,” Quenette said. “I don’t lose any sleep over it. I get

frustrated over it. … There is no demand for office or retail space in

downtown. All you have to do is look at all the vacant spaces.”

Quenette

says the city should listen to outside developers. A case in point is

an Indianapolis firm that walked away after the city rejected the idea

of 200 apartments on the YWCA block.

“The

city’s kind of told the developer, ‘We don’t want you to build 200

housing units here because it’s too dense,’” Quenette says. “That’s kind

of shooting yourself in the foot, isn’t it? That particular company

does that kind of development throughout the Midwest.

You don’t tell them they don’t know what they’re talking about.”

Quenette

also criticizes the mayor’s proposal to spend $425,000 in TIF funds to

purchase a vacant building on the Old State Capitol Plaza that once

housed a surveying museum that received $118,000 in TIF funds for

renovations in 2008. The museum closed in 2013, less than three years

after it opened. Now, Langfelder is trying to cobble together tenants.

Prospects have included the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People, Benedictine University, the University of Illinois

Springfield and the city’s Convention and Visitors Bureau, which is now

leasing space in another downtown building. None of the mayor’s proposed

tenants are subject to sales or property taxes, and the building itself

would be removed from property tax rolls if the city buys it.

“If

the mayor wants to buy a building, have him put it in his budget – it

shouldn’t come from TIF funds,” Quenette says. “A lot of the TIF money

in Springfield has been used for entities that don’t pay property taxes.

When you do that, it may make an improvement that makes an area look

better, but it’s not building the (tax) base, and it’s not increasing

the amount of money flowing into the fund. It’s not achieving its

original purpose.”

Downtown

Springfield, Inc. is drafting a policy on how to prioritize TIF

spending, Clemmons Stott says, with an overall goal of making vacant

buildings livable. While DSI doesn’t have a position on whether a park

should replace the YWCA building, Clemmons Stott doesn’t sound like

she’s on board, at least not yet.

“When

you spend $1.5 million in TIF, you expect it to create some type of an

increment (increase in tax base),” Clemmons Stott said. “We never

thought there wouldn’t be an increment-producing project on that block.

...

The question that

Downtown Springfield, Inc. always asks is, how can we attract more

people downtown. If a park is a thing that will do that, we would be for

it. But we do think there needs to be some kind of vision.”

Clemmons

Stott says that TIF alone isn’t the answer to downtown’s woes. For

example, new businesses often need help with rent that TIF hasn’t been

able to provide, she said.

“We’re still missing that kind of assistance for new businesses,” she said. “We’re putting all our eggs in the TIF basket.”

Beyond

TIF If anyone has skin in the downtown game, it’s Chris Stone, a

lobbyist turned real estate speculator turned owner of Lucy’s Place

gambling parlors, turned CEO of HCI Alternatives, a medical marijuana

dispensary company with outlets downtown and in Collinsville.

In

2012, an ownership group that included Stone acquired the Bressmer

building and adjoining Mendenhall building on Adams Street. The annual

property tax bill exceeds $90,000. The Mendenhall building now houses

HCI Alternatives; the Bressmer building is vacant. It was once home to a

department store, then became headquarters for the Illinois Department

of Commerce and Economic Opportunity, which departed in 2010. The

buildings are valued at slightly more than $3.4 million, according to

Sangamon County property records; in 1994, they sold for $45.7 million.

It’s not clear just how much Stone, who says that he’s now sole owner of

the Bressmer, has invested in the properties – county records show the

sale amount in 2012 as zero, with records in the recorder’s office

showing they were deeded over in lieu of foreclosure.

Stone

agrees with critics who say that too many projects have gotten TIF

money without raising the tax base. If the powers that be decide that a

park should go on the YWCA block, he says, then the state should buy the

site back from the city and do it.

“We

in the city of Springfield have made many bad decisions on development,

and it has to stop,” Stone says. “I’d like to see it (downtown) get

better. I think everybody’d like to see it get better.”

Stone

says that TIF isn’t the only tool the city should be using to encourage

development. The city should enact more developer-friendly regulations

for downtown, Stone says. There should be less expensive ways to address

asbestos and lead paint issues in downtown buildings than are currently

in place, he says. Sprinklers are another issue.

“These

buildings are over 100 years old – they’ve survived for over 100 years

without burning down,” Stone says. “Why do you have to spend $100,000 on

sprinklers?” Then again, the Bressmer building was gutted in a 1948

blaze that was the biggest fire in Springfield history at the time.

Despite $2 million in damage (the equivalent of more than $20 million

today), the exterior and support structures remained sound, and so the

Bressmer was rebuilt using much of the original steel and stone. It now

has fire sprinklers.

Stone’s

list of suggestions is long. Reduce permitting fees. Consider property

tax abatement and breaks on utilities. Lure tech companies with

opportunities to build data storage facilities on the east and south

sides of town while providing office space downtown. Convince the health

care industry to put operations downtown, including a clinic for

municipal employees. Move the farmers market from Adams Street to

grounds surrounding the Old State Capitol, where traffic wouldn’t be

disrupted, and offer free parking on market days within three blocks of the

market. Move the College of Public Affairs and Administration from the

University of Illinois Springfield campus on the southern edge of town

to downtown, where students would be closer to state offices and the

General Assembly, where they might hope to work someday. Improve bicycle

lanes and start up a bicycle-sharing program similar to the one in

place in Chicago. And replace antiquated parking meters with ones that

will accept payments via credit cards or cellphones, an idea endorsed by

Ald. Proctor.

Notably

absent from Stone’s list is retail development. Pointing to parts of

downtown Chicago that are largely empty after dark, he says that

Springfield doesn’t necessarily need a lot of downtown retail

development.

Notably

absent from Stone’s list is retail development. Pointing to parts of

downtown Chicago that are largely empty after dark, he says that

Springfield doesn’t necessarily need a lot of downtown retail

development.

“I think

everybody’s vision that we have to have vibrant restaurants and we have

to have all this shopping, you don’t have to have all that in order for

Springfield to have a vibrant downtown,” Stone says.

The here and now Nothing downtown happens overnight. Ask Rick Lawrence.

Lawrence

was granted $1.9 million in TIF money more than two years ago to rehab

buildings at the intersection of Sixth Street and Monroe – he owns three

– into apartments and office space. He has yet to finish any apartments

and isn’t sure whether there will be 17 or twice that number.

Renovating old buildings, he allows, has been more difficult than he’d

imagined.

“It’s been a very slow process,” Lawrence says.

“It’s a lot more involved than I expected. … It just requires a lot of tender care to bring it back to what I would call current standards.”

From

the street, at least, it looks like he’s going backward, given that

Café Brio, a restaurant on the ground floor of one of the buildings

smack in the middle of downtown, closed late last year. It’s one of the

most prominent intersections in downtown, the last place anyone wants to

see a “For Lease” sign.

“I feel horrible – I wish that hadn’t happened,” Clemmons Stott says. “I don’t think that will be vacant for very long.”

Lawrence

said he’s grown attached to his works-in-progress and would do it all

over again. He says he’s hopeful about downtown’s future and his

project. But it isn’t easy.

“I’m

in the survival mode, trying to survive the curse of an historic

building,” Lawrence says. “Now, I’m into it, and I’ve got to stick it

out and get it done. … My fingers are crossed that I can accomplish my

goals and keep the city and everybody happy and give them a nice

facility.”

Clemmons

Stott remains optimistic. The city has done a good job on streetscapes

and sprucing up building facades, she says, and there is interest in

residential development even without subsidies. After the city in 2015

rejected TIF funding for a new apartment building near Near North

Village, Bluffstone, an Iowa-based company, built it with private money,

adding nearly 80 units to downtown housing stock. It’s the sort of

thing recommended by a team of architects and urban planners who

authored a 2012 study that says residential development is the key to

downtown revitalization.

The

2012 analysis was more a set of guidelines than a plan akin to master

plans for other areas of the city such as Enos Park, MacArthur Boulevard

and the Medical District that include broad goals as well as specific

ideas for specific streets and pieces of land in addition to zoning

proposals, strategies to accomplish development and, in some cases,

timelines for getting things done. Clemmons Stott, who co-chaired a

nowdefunct committee formed under former Mayor Houston that was charged

with implementing ideas contained in the 2012 study, says that downtown

would benefit from the same sort of planning effort. It goes back to the

vision thing.

“Downtown

does not have a master plan,” Clemmons Stott says. “We are at the

center of the entire county. A lot of people have hopes and dreams

wrapped up into it. … Vision, I think, is a very important thing that I

want to focus on.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].