Damage, economics may doom historic YWCA building

Before he was president, state senator Barack Obama used to kid Mary Hardy Hall of Springfield about the outdated manual elevator at the YWCA.

“ ‘If it isn’t the woman with the oldest elevator in Springfield,’ ” Hardy Hall says with a laugh, imitating Obama. She was the last director of the Young Women’s Christian Association in Springfield before it closed its doors in 2007.

That the future president sometimes visited the YWCA is only a small piece of the building’s rich history. Over the years, it has hosted women and children in need, sports teams, public meetings, classes, social events and more, making it an important cultural center in Springfield for nearly 100 years.

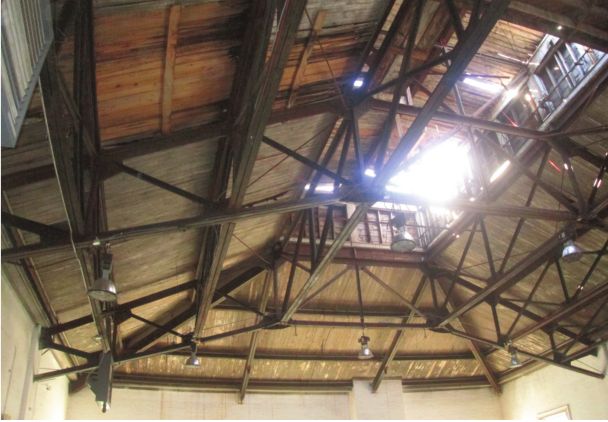

In 2006, the roof over the pool and gymnasium was damaged by the powerful storm that ripped through Springfield that year, and the YWCA was only able to raise enough money for a temporary patch. It ended up being the death blow to an organization which had been struggling financially for years.

Now, the roof has decayed, leaving the interior open to the sky. Dirty water covers the bottom of the pool, and the floor is littered with peeled paint and pieces of the ceiling. Mold and algae have proliferated, and exterior bricks from the top of the southeast corner fell to the sidewalk a few years ago. City inspectors say the building is unsafe.

Still, preservationists say the building is structurally sound and should be repurposed. They note that the eastern half of the building hasn’t seen the same deterioration as the western half that holds the pool. Sure the building needs repairs, they say, but its historical and cultural significance would certainly justify such an investment.

Significance may not be enough to save the YWCA. Springfield Mayor Jim Langfelder wants to tear the building down so the city can move on with plans to redevelop a downtown block that has languished in disuse for too long. Only a couple of procedural hurdles stand in the way of the YWCA’s demolition, and those dominoes are merely waiting for their turn to fall.

For nearly a century, the Young Women’s Christian Association building in downtown Springfield was a safe haven. Opened in March 1913, the YWCA was an oasis of racial and religious tolerance – one of a network of YWCAs around the nation which made equality and integration part of their mission long before that was common or widespread.

Hardy Hall says it was one of the few places in Springfield where African-Americans were allowed to swim during the 1960s. She says that in the 1990s, Muslim women had a private swim time so they could use the pool without compromising their beliefs. It was a place homeless people could shower for a nominal fee. The organization also offered programs like job training, after-school programs and life skills classes for women and children.

On the national level, the YWCA has been on the forefront of social change since its inception in 1858 as the Ladies Christian Association in New York. The group modeled inclusion and often intentionally went against the grain of popular thought. In 1877, the YWCA offered calisthenics for women, dispelling the myth that women were too frail to exercise. The first African-American YWCA and the first Native American YWCA opened in 1889 and 1890, respectively, catering to groups which were still considered “other” in white society.

The YWCA established sex education in 1906, held its first interracial conference in 1915, called together the first-ever conference of women physicians in 1919, publicly opposed lynching and mob violence against African-Americans in 1934, opened the first integrated public dining facility in Atlanta in 1960, and was a sponsor of the famous 1963 March on Washington, at which Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech.

As part of the national network and through its own contributions, the YWCA in Springfield is part of that legacy.

Although the Springfield YWCA building isn’t listed individually on the National Register of Historic Places, it’s included on the register as a contributing building in the Central Springfield Historic District. In 1997, the city council designated the YWCA as a local landmark, and this year preservation group Landmarks Illinois named the building as one of the state’s most endangered historic sites.

The YWCA was one of the most popular organizations in Springfield shortly after its founding, but membership was flagging by the 1990s, Hardy Hall says. Before she took over at the YWCA some time in the early 2000s, the group had taken out a mortgage just to pay for building maintenance. Facing foreclosure in 2007, the YWCA moved out and sold the building in 2007 to a company hoping to redevelop it into residential space.

In December 2008, six members of the Springfield City Council voted down a measure which would have offered the company $2.5 million in tax-increment finance (TIF) money to help renovate the YWCA. Had that deal been approved, the building would likely be in use today. The city eventually spent $25,000 to buy the building in 2014.

Now, the city has another opportunity to see the YWCA building repurposed with TIF money. Indiana-based development firm Flaherty & Collins Properties wants to renovate the building at an estimated cost of $7-9 million. It would be part of a larger plan for the rest of the empty YWCA block.

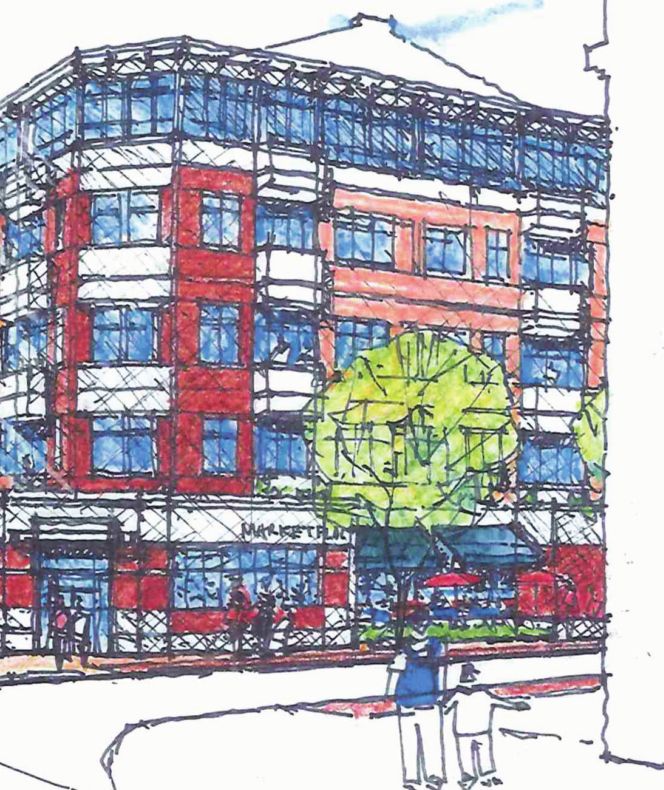

The plan calls for 24 residential units in three floors of the YWCA, plus new construction which would include a mix of retail shops and townhomes at street level and 200 apartments in floors two through five. A parking ramp would be hidden behind the apartments, and a small public park would cover the southwest corner of the block, under which runs the city’s flood-prone Town Branch sewer. The development may use solar power, geothermal climate control and other “green” designs. Flaherty & Collins hopes to start construction in May 2017 and finish in October 2018.

A spokesman for Flaherty & Collins forwarded a request for comment to Julie Collier, vice president for development with the company. Collier didn’t respond to that request, an additional email or a phone message seeking comment.

Seth

Molen Construction of Springfield also submitted a proposal for the

YWCA building, which calls for first demolishing the deteriorated

western half of the building containing the pool and gym. The remaining

eastern half would be renovated into eight large apartments at 1,200

square feet each. The company didn’t propose any new construction for

the rest of the block. Langfelder says he turned down the plan because

it would require the city to handle demolishing the western portion,

which could create liability if the demolition goes awry.

Instead

of a formal proposal, Massie Massie and Associates landscape

architects of Springfield submitted a letter asking the city to

consider turning the YWCA block into a public park to complement the

planned renovation of the Illinois Executive Mansion and establishment

of Jackson Avenue as a walking corridor that would connect the Lincoln

Home with the Illinois Statehouse. The letter notes that there are

plenty of other empty buildings in downtown Springfield which could be

used for new apartments and retail space.

Langfelder

says he prefers the Flaherty & Collins proposal. Originally,

Flaherty & Collins told Langfelder that the funding gap – the

difference between what their proposal would cost and what the company

would be willing to pay – was $17 million. Langfelder says he asked

about the cost to only renovate the YWCA, which is where the $7-9

million figure comes from. He says historic preservation tax incentives

could fund about one quarter of the cost for the Y renovation, but the

cost would still be more than he’s comfortable spending from the

city’s downtown TIF fund.

Although

Langfelder is pursuing the building’s demolition, he’s not happy about

it. He says if someone came forward with $7 million of their own money

to turn the YWCA into a community center or museum, he’d consider the

offer. Langfelder adds that his mother is unhappy with him for pursuing

demolition.

“I’m

getting grief from my mother,” Langfelder says. “Every day, she’s asking

‘You can’t find someone for the Y?’ She served on the board; I know

the history of it.”

Karen Conn of Conn Hospitality Group in

Springfield is a member of the Springfield Economic Development

Commission, which advises the city on project proposals that may benefit

the local economy. Conn says she and her husband, Court, approached the

city during the administration of former mayor Mike Houston about

buying the building and renovating it, but they were rebuffed. Conn,

whose past successes at historical renovation include the Inn at 835,

Obed and Isaac’s brewery and Wm. Van’s Coffee House, says the city just

wanted the building gone. While Conn says she doesn’t think the current

administration is completely closedminded toward saving the YWCA, she

chastises Langfelder for pushing to demolish it.

“If

we don’t stop tearing our buildings down and building new buildings,

we’re going to look like every other city,” Conn said. “People come to

Springfield to see uniqueness and charm, to see what it looked like when

Lincoln lived here. … We’ve got to stop tearing down our history.”

Conn

laments that she currently has her hands full with the new Obed &

Isaac’s brew pub in Peoria, or she would be pursuing the YWCA building

herself. While she says it probably doesn’t make financial sense for a

developer to rehabilitate the building using only private cash, she also

doesn’t believe the city would need to foot the entire bill.

“I

can line up 10,000 developers who would take that deal, because it’s

zero investment and all profit,” she said, referring to a scenario in

which the city funds the entire renovation.

How

much the city should chip in is a judgment call, Conn says, but that

decision is impossible to make without more information about the

project. She says details like how much remedial work would need to

happen inside the building and the finish level of the apartments can

make all the difference.

“If you want a new car, it’s going to cost $20,000,” she said. “But you didn’t say whether you want a Ford Fiesta or a Bentley.”

Karen

Conn isn’t the only one stumped by that lack of information. It was

also the reason the Springfield Historical Sites Commission on Oct. 18

denied the city’s request to demolish the YWCA.

The

commission is tasked with cataloguing Springfield’s historic sites and

protecting their historic character. The city ordinance governing

historic structures lays out criteria for when the commission can

approve a demolition, and the ordinance directs the commission to

consider factors like a building’s condition and whether the proposed

work would result in changes in the essential historical, cultural, or

aesthetic character of the area.

However,

the city asked the commission to instead consider a separate part of

the ordinance, which grants the commission power to approve demolition

if a historic building represents an unreasonable economic hardship for

the owner – in this case, the city. Given little financial data besides

the developer’s $7-9 million rehabilitation estimate, the commission concluded it couldn’t determine whether an economic hardship actually exists.

The

ordinance also gives the Springfield City Council power to approve,

modify or reject a commission decision on appeal, meaning the city may

ask the council to override the commission. A few hours after the

commission’s Oct. 18 vote to deny demolition, the city council approved

by a vote of 8-2 a contract with a Chicago-based company to demolish the

YWCA. That contract vote likely predicts how the council vote would

fall if asked to override the commission’s decision.

For

now, Langfelder says he’s not sure whether he’ll appeal to the city

council or whether he’ll return to the Historic Sites Commission with

more information and ask for a new vote. That largely depends on the

financial details Flaherty & Collins provides to the city,

Langfelder says.

Each

of Flaherty & Collins’ other projects listed in the bid packet

submitted to the city received some level of public financing, ranging

from just 7.7 percent for a $39 million project in Cincinnati to 49.6

percent public financing for a $26 million project in Kokomo, Indiana.

Frank

Butterfield, director of the Springfield office of preservation group

Landmarks Illinois, says it’s “absurd” to think that the City of

Springfield would have to pay the full cost of renovating the YWCA. He

questions why the building needs to be demolished now, when there’s no

official agreement with a developer yet.

“The

city seems eager to be creative on new construction, but not on the

YWCA,” Butterfield said. “What we’ve heard so far from the city (to

preservationists) is, ‘You tried. Too bad. You’re gone.’ ”

While it’s hard to put a

dollar figure on the value of history, Butterfield says economic studies

have shown that a diverse variety of age and scale among buildings

tends to attract the most people. He adds that people in urban areas

tend to gather in older, denser neighborhoods.

“One individual building may be a riddle that’s hard to solve,” he

said, “but if you look at it as a whole neighborhood, the evidence is on

the side of reusing old buildings.”

Springfield

architect and preservationist Mike Jackson concedes that the apartments

proposed for the YWCA building by Flaherty & Collins would have to

be top-of-the-market to even come close to making financial sense for

the developer without a subsidy. However, Jackson looks at the project

as an investment in the downtown’s future. He says a $7 million project

downtown would produce nearly $2 million in tax revenue over 10 years

for the same TIF district from which the initial funding would come.

In

the meantime, Jackson says, the city should use the money it would have

spent on demolition and instead fix the building’s roof.

“This building has lasted for a century and can survive for another century with the right team,” he says.

Even

if the city gets a more detailed cost estimate for the building, the

final decision will be a value judgment that pits financial investment

against the value of history.

Karen Conn already knows on which side she falls.

“I will chain myself to the building when the wrecking ball comes,” Conn said, “and I’ll grab the mayor’s mother to join me.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].