The state’s monuments to the past are in spiraling disrepair and their communities despair over the ultimate fate of these endangered sites, a BGA Rescuing Illinois report finds.

PRESERVATION | Judith Crown, Better Government Association

Illinois’ history is crumbling away.

Mansions, museums and monuments that showcase Illinois’ past, and honor famous luminaries, ranging from President Abraham Lincoln to famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright, have been battered by years of fiscal decline and subsequent state-imposed austerity measures, according to a BGA Rescuing Illinois investigation.

The 56 sites operated by the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency (IHPA) require nearly $146 million of dollars in deferred maintenance through 2020. Many of the buildings’ plumbing, electrical, heating and cooling systems have outlived their useful lives, according to interviews with IHPA officials and documents obtained by the BGA under the Freedom of Information Act.

In recent years, staffing has been reduced two-thirds to 48 full-time employees, according to data from the IHPA division running the 56 historic sites, and most of the venues are now closed on Mondays and Tuesdays, according to their websites. The Lincoln Tomb, an exception, is open seven days a week.

Some locations, including Shawneetown Bank and the Crenshaw House State Historic Site, both in far downstate Gallatin County, have been closed to visitors. Other attractions can be seen only by appointment.

Also closed are the Illinois State Museum and its five branches, which focus on the state’s natural and cultural history, and are run by the Department of Natural Resources (DNR). Last summer, Gov. Bruce Rauner closed them citing budgetary reasons, but the administration now plans to reopen most of the museum facilities next month.

The neglect puts key historical markers, and state tourism dollars, at risk. It’s also straining the civic connection many local communities have with these sites, which are used by schoolchildren for educational purposes and as a point of pride for residents.

The mark of Abraham Lincoln – the state’s main historical attraction – can be found beyond the newer Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield. The reconstructed village of New Salem shows where Lincoln lived as a young man, and the Lincoln Log Cabin near Charleston preserves the site of the last home and farm of the president’s father and stepmother.

“These sites are jewels, we can’t ignore them,” said Rep. John Cavaletto, R-Salem, whose district includes the Vandalia State House, the state Capitol from 1836 until 1839 and where Lincoln served as a young representative. “They must be taken care of and coddled.”

Beyond Lincoln

Other locations reflect the state’s cultural diversity. Cahokia Mounds, a UNESCO World Heritage Site near Collinsville, is the home of the largest prehistoric Native American city north of Mexico. Galesburg hosts the birthplace of the poet Carl Sandburg, and Galena is the former home of Ulysses S. Grant, the Civil War general and U.S. president.

Advocates for museums and historic preservation acknowledge that it’s difficult for historic sites to compete with critical public services for scarce resources. For that reason, they say, a new model is needed, such as private-public partnerships. Already, volunteers are being trained as interpretive guides.

Local foundations and community groups are raising funds for repairs and maintenance and pitching in to beautify the grounds – although state officials doubt these drives will come close to filling the agency’s outsized needs.

A 2008 survey conducted for the state of Illinois by the Boston architectural and engineering firm VFA Inc. estimated that IHPA sites required funding of $146 million for deferred maintenance through 2020. IHPA facility manager Michael Norris said that although some deficiencies may have been addressed, underpinnings of historic sites likely have further deteriorated since that report.

The agency has an annual maintenance budget of $75,000, which covers only the most routine repairs.

When an air conditioning unit was vandalized at the Lewis and Clark State Historic Site in 2014, the agency received emergency funding of $65,000 from the Capital Development Board (CDB) for the repair, Norris said.

Repair, restoration

Each

year IHPA requests funding for its most pressing needs through CDB,

which manages state capital projects. For the 2016 fiscal year, it

identified 23 repairs, restorations and replacements amounting to more

than $37 million. Among the most urgent: $2.2 million is needed to

repair and restore the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Dana-Thomas House in

Springfield, including the storm water drainage system. The Lincoln Tomb

in Springfield requires $1.1 million for masonry and other site

repairs. The New Salem site needs $2.1 million to update heating and

cooling systems, repair or replace the sewer system and upgrade

electrical service at the campground.

None

of the projects proposed in the past three years have been funded,

according to Ryan Prehn, superintendent of state historic sites for

IHPA.

At the Vandalia

State House, water has damaged wood windowpanes and plaster on the wall,

according to Cavaletto. Replacing 33 windows will cost nearly $100,000,

he estimates. A local nonprofit is working to raise funds for the

repairs. But Cavaletto said the state must raise revenue to take care of

Vandalia and other sites. Though he doesn’t relish the idea of gaming,

one option is an instant lottery scratch-off ticket, from which proceeds

would be dedicated to the upkeep of historic sites – similar to the

ticket that raises cash for veterans programs. Vandalia and other

historic sites, he adds, should be open seven days a week, especially

during the summer tourist season. “That would give an economic boost to

the area,” he said. “If we limit hours, we cut our own throats.”

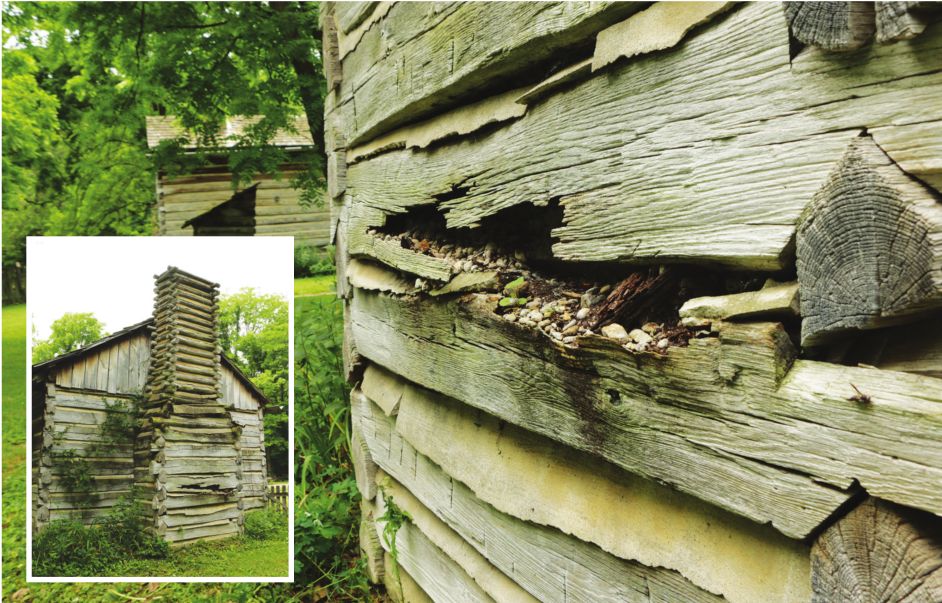

In

New Salem, water has sometimes damaged log cabins, most of which were

constructed during the 1930s under the New Deal’s Civilian Conservation

Corps program. Moss has overtaken the roof of an old barn, which

indicates that water is being retained in the underlying structure, said

IHPA architect Jane Rhetta. If that were ignored over time, she said,

“the structural integrity of the building could be threatened.”

Elsewhere on the site, water has damaged the chimney assembly of three cabins, which also will require restoration.

This

work isn’t even on the official requisition list, Rhetta said. It will

involve obtaining estimates from specialists in historic restoration,

then working with a local nonprofit to raise the funds.

Rescue volunteers

Staffing

has been cut at New Salem to eight full-time employees from 22 in 2002.

In addition, the site used to employ seasonal workers from May to

October to demonstrate blacksmithing, weaving and other oldfashioned

crafts. Now the site draws on a roster of volunteers.

New

Salem is well staffed in comparison to other sites, many of which have a

single full-time, or contract employee. At Bishop Hill, the site of a

utopian religious community founded by Swedish immigrants, staffing has

been cut in half to three from six in 2002. The state operates four of

the site’s 18 buildings while others are operated by the nonprofit

Bishop Hill Heritage Association and other local groups that have picked

up some of the slack.

The

Heritage Association last year took over the autumn harvest festival,

modeled on a late 19 th century county fair with food, music, dancing

and crafts. Funding had fallen to about $2,000 a year from a peak of

roughly $10,000 in the late 1980s. “We’ve been able to increase the

support, although we’re not at the level of the heyday,” said

administrator Todd DeDecker.

DeDecker said the

association raises money in the United States and abroad. “In Sweden,

we’re a big thing,” he said. “We get a lot of Swedish visitors.”

The

combination of lack of reinvestment in historical sites and limited

marketing dollars could hurt in-state tourism and related economic

activity.

The

Department of Tourism through its $65 million budget promotes the state

broadly and also funnels money to local convention and visitor bureaus.

IHPA doesn’t have its own marketing budget to promote the sites,

according to IHPA’s Prehn.

A

recent study for the Illinois Council of Convention and Visitor Bureaus

by industry consultant Tourism Economics projected that a 20 percent

budget reduction would cost the state $2.3 billion in visitor spending

and 4,600 jobs.

A new model?

Given the immense requirements for the state’s historic sites in an era of scarce resources, what can be done?

It’s

not just physical repairs that are needed, advocates say. The state

needs to invest in order to properly market these destinations to

prospective visitors in Illinois and out of state, and then offer a

top-notch experience when they arrive.

For

example, Cahokia Mounds, outside St. Louis, falls under the radar. It

has a valuable interpretive center and museum, said Jean Follett, a

Wheaton-based consultant and board member of the Chicago

nonprofit organization, Landmarks Illinois. But signage isn’t adequate

and there aren’t enough places to eat and shop, she added. “The

surroundings are depressing,” Follett said. “They need to do more to

promote it.”

For Follett, the overarching problem is that over the years, the state took on more sites than it could handle.

“There are way too many,” she said. “This is not a model that we can support.”

The

state, she added, should hang on to locations that are truly historic,

and cede control for others to local nonprofits and friends groups.

The

possibility of private-public partnerships has been proposed by Rep.

Don Moffitt, R-Galesburg, whose district includes the Carl Sandburg

State Historic Site.

Last

year he introduced a bill that would authorize IHPA to team up with

private companies, colleges or other nonprofits to oversee maintenance

and administration of 10 sites in a pilot project. The bill was referred

to committee. Moffitt maintains such partnerships could offer a way to

salvage and promote sites that are languishing.

The Sandburg site is open only Thursday through Sunday and is run day-to-day by a single contract employee.

Moffitt

said Galesburg-based Knox College would be an ideal partner. Student

interns, for example, could be recruited to assist with operations and

marketing. “A site like this should be viewed as an economic engine,” he

said.

Karrie

Heartlein, director of government and community relations at Knox, said

the college would welcome the opportunity to collaborate. She said Knox

in the past has discussed with state officials the idea of students

serving as docents, assisting in preservation efforts or developing new

exhibits. The idea of the college’s staff assisting with building and

ground maintenance hasn’t been explored. “We don’t want the Sandburg

home to fall into disrepair but we don’t want to steal thunder from

volunteers who have been active,” she said.

Privatization concerns

Museum

specialists acknowledge that such partnerships may be inevitable but

they worry about the potential for private groups to skew historic

interpretation.

In a statement last year reacting to Moffitt’s bill, the Illinois Association of Museums (IAM) warned of a “slippery slope.”

“Privatization

raises serious questions about corporate influence, voices of

authority, proper care of the state’s historic resources and artifacts

and subjective interpretation of Illinois history,” the association

said. “IAM believes that it is the state’s responsibility to care for

its history and historic properties and it should not be the

responsibility of private individuals or companies to operate state

historic sites.”

Jeanne

Schultz Angel, former IAM executive director, now executive director of

The Nineteenth Century Club and Charitable Association in Oak Park,

said nonprofit organizations such as colleges and universities would

likely prove judicious guardians of historic sites.

But

she worries that acquisition by corporations or wealthy donors could

lead to subjective inclusions and omissions of stories – whether

deliberate or due to a lack of knowledge, adding, “the public voice is

lost.”

Judith Crown

is a business journalist, who has worked for major news outlets

including BusinessWeek Chicago and Crain’s Chicago Business. She has

covered public fi nanace stories for the BGA and can be contacted at [email protected].