Jim Langfelder’s first year as mayor

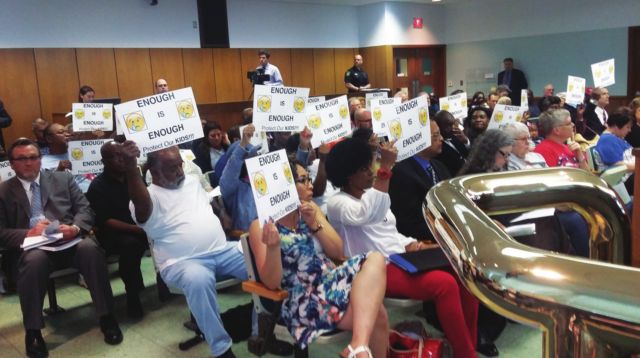

It took nearly a year for the honeymoon to end, but Mayor Jim Langfelder this spring finally faced a room full of constituents angry at him.

City council chambers in April bulged with people clutching signs: “Enough is enough: Protect our kids.” The signs were held high as speaker after speaker attacked a scheme to move a planned Salvation Army homeless shelter from Ninth Street, where construction unexpectedly stopped in February, to the bankrupt Gold’s Gym, which closed last fall. At a prior council meeting held four days after the mayor announced the move to Gold’s Gym, someone called the mayor a dictator.

“We are tired of things being shoved down our throats on the east side,” Teresa Haley, head of both the state and local chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, told the council last month. “We are a community. We are taxpayers, like everyone else. And enough is enough.”

The Salvation Army controversy is proving a challenge, some might say pratfall, for a mayor who presumably should be versed on the art of politics and making deals, having been city treasurer for a dozen years prior to being elected mayor a year ago.

The Salvation Army saga notwithstanding, Langfelder has generally won kudos for communication skills – even aldermen who’ve grumbled about not getting advance word of mayoral initiatives acknowledge that Langfelder returns phone calls. During his first year as mayor, he shepherded big changes at City Water, Light and Power through the city council with no serious opposition. Less than three months after taking office, the mayor’s support for Hunter Lake was backed by a 9-1 vote from aldermen who endorsed the idea of creating a backup water supply that’s been on and off the drawing board since the 1950s. He’s sticking to his guns on a residency requirement for city employees, and he’s played tough with the firefighters’ union, moving to eliminate holiday pay from pension calculations in an effort to cut costs for the city.

There have been bumps, notably redevelopment of the North Mansion Block, site of the long-shuttered downtown YWCA. But no bump has proven as big as the Salvation Army imbroglio.

The Springfield Mass Transit District wants to move the downtown bus transfer station from Capitol Avenue to land just north of the county courthouse on Ninth Street, which would displace a Horace Mann parking lot. The solution? Put a new parking lot for the company on the Salvation Army’s adjacent land and push the charity elsewhere.

Sangamon County board chairman Andy Van Meter confirms that he told the mayor last fall that Horace Mann needed a new parking lot. In February, Langfelder quietly asked the Salvation Army to stop work on the homeless shelter.

When the media in March reported that work on the shelter had stopped, forcing the mayor to respond, Langfelder didn’t tell the whole story. Instead of saying that Horace Mann wanted the land for a parking lot, the mayor said the homeless shelter might be too close to adjacent railroad tracks and that a planned, but unfunded, railroad relocation project might somehow force the shelter to move. It seemed an odd reason. After all, the tracks and the building due for conversion to a homeless shelter had been in place long before the Salvation Army paid $3.4 million for the land in 2009. And the charity’s property isn’t on the acquisition list to make room for more train tracks. Van Meter says that the downtown bus transfer center on Capitol Avenue needs to move regardless of railroad relocation that is far from a done deal.

The

mayor now says that moving the Salvation Army would create a blank

canvas for development on Ninth Street that could eventually include a

train station. Just what the homeless shelter would be has been a work

in progress. The Ninth Street site was going to house both men and

women; after residents near Gold’s Gym objected, Langfelder and the

Salvation Army said that the new location would be for families only.

The mayor and the charity also have suggested that a gym-turnedshelter

could double as a community center, something residents have long

wanted, but there have been no concrete plans or funding unveiled.

If

there is a grand vision, it has emerged in drip-drip fashion, creating

the appearance that Langfelder is making this up as he goes along. It’s

like watching a high-wire act, with the mayor the sole performer and the

end game uncertain.

“This

whole process is convoluted,” says Ward 2 Ald. Herman Senor, whose ward

includes Gold’s Gym. “I think the residents have been listening to two

or three different stories, and they don’t know who to believe.”

Compounding

the lack of early full disclosure about Horace Mann’s need for a

parking lot was Langfelder’s awkward announcement last month that Gold’s

Gym would be converted to a homeless shelter. The press conference in

city council chambers on April Fool’s Day was made with short notice to

Senor, contrary to custom that dictates aldermen should be told well in

advance when something their constituents won’t like is en route. The

mayor later apologized for holding the press conference, but the damage

has been done.

“We

were watching the news one night and it was like, ‘What the hell?’”

Haley says in an interview. “The mayor is apparently friends with

someone over at Horace Mann, and they said, ‘Make this happen.’” Ward 7

Ald. Joe McMenamin says the mayor is well-intentioned in finding a new

home for Salvation Army, but he appears to be carrying water for SMTD

and Sangamon County.

“He

wastes a lot of political capital on this and upset, not just Herman

Senor, but the other aldermen,” McMenamin said. “The mayor should have

gotten some advice from the aldermen. It was both a political mistake

and a strategic mistake. … The mayor’s in the arena taking all these

shots. SMTD and the county and Van Meter are looking down from the top

row while Langfelder’s doing their dirty work for them. That’s what it

looks like to me.”

The

mayor will have none of it. When Senor during a council meeting last

month suggested that a homeless shelter was being pushed into his ward

to benefit Horace Mann, Langfelder flat denied it. And strongly.

“If

anyone wants to play the blame game, they can blame me,” Langfelder

said. “I’ve been pretty upfront in these discussions. You can only blame

me. It’s not Horace Mann, it’s not the Salvation Army, it’s the

direction the city should take. We have to take a different step to take

the city forward.”

During

an hour-long interview about his first year in office, Langfelder said

he’s focused on the charity, not Horace Mann. While the process has

appeared piecemeal, Langfelder said that he always intended to move in a

“progressive manner.”

“I’ve

inherited the mess, and I’m going to deal with it,” the mayor says.

“Some people can handle the political heat, some people can’t. I can

handle the political heat.”

Downtown development

While

Senor isn’t happy about the way the Salvation Army saga has unfolded,

he says that he would give the mayor between a B and B-minus grade for

his first year in office.

Senor

says that the mayor deserves praise for appointing the first-ever

Springfield economic development commission that evaluates TIF projects

before they go to aldermen for a vote. Still, he says that development

proposals could have been handled better.

Early

in Langfelder’s tenure, the city council unanimously rejected a TIF

subsidy for a downtown student housing project. The rejection came after

organized labor objected – the modular housing would be built

elsewhere, then trucked to town, so there would be few, if any, local

construction jobs created. The project, which is proceeding without TIF

money, was hatched before Langfelder took office, but Senor says he

wonders whether the mayor’s office could have worked with the developer

to come up with a project that would have created both jobs and housing.

The

North Mansion block, site of the shuttered downtown YWCA, has gotten

off to a slow start. The city is already into the deal for more than

$1.5 million, the price it paid for the land in 2014, and Langfelder

professed surprise last year when a development consultant he wanted to

hire for more than $125,000 told the Economic Development Commission

that the project – whatever it might be – would require a public subsidy

of $30 million or more.

During

the campaign, Langfelder said he wanted to see development that would

encourage people to live and work downtown, but he hasn’t gotten more

specific than that. One year into Langfelder’s term, the city still has

no plan for the property. Langfelder’s administration initially said

that the crumbling YWCA building would have to be demolished, but that’s

no longer certain as preservationists have insisted that the structure

can be saved. The mayor’s proposal to spend $125,000 on Stantec, the

development consultant, to administer the project was unanimously

rejected by the city council in January after being approved by a 5-2

vote by the Economic Development Commission. But the mayor wouldn’t let

go entirely and so retained the firm to help solicit proposals from

developers at a cost of less than $25,000, an amount that doesn’t

require council approval.

The

city has received just two formal proposals. Last June, the city heard

from seven would-be developers who expressed interest before the mayor

decided to start from scratch. Bottom line, the city appears no closer

to figuring out what should be done with the property than when

Langfelder took office.

“There’s a misstep – I’ll say the ‘s’ word: Stantec,” the mayor allows. “I took the heat on that.”

Why? Surely the mayor could count votes and knew that the council would reject hiring Stantec.

“You have to support your directors – I supported my director in that regard,” Langfelder explains.

Karen

Davis, the city’s economic development director, had worked with

Stantec on projects in St. Louis and brought the firm to Springfield.

Langfelder says that the city needs help and views from outside the city

to make progress.

“Quite

frankly, what a lot of people like is the cozy atmosphere here in

Springfield,” Langfelder says. “What we need to do is be more

progressive on how we approach things.”

While

the mayor says that bringing in development experts from outside the

city and opening the TIF process by having the Economic Development

Commission review projects is good for the city and helps depoliticize

the development process, he hasn’t been able to point to any big

successes during his first year in office. Economic development, the

mayor says, doesn’t happen overnight.

“They (critics) want to see buildings coming out of the ground,” the mayor says.

High marks for CWLP

The

city, however, needs a “strong foundation” to attract economic

development, Langfelder said, and part of that is stabilizing CWLP’s

finances.

The mayor wins high marks

for his administration of CWLP. Similar to Senor, McMenamin gives

Langfelder a B-minus when it comes to his first year as mayor, but when

it comes to CWLP, the alderman says the mayor gets an A.

Between

refinancing $500 million in debt and renegotiating the utility’s coal

contract to lower fuel costs, the mayor has charted a course to

financial stability for the utility, which had needed an infusion of

cash from the city’s corporate fund to maintain a sketchy bond rating.

Under Langfelder, bond rating agencies have improved CWLP’s credit

rating, and last fall’s refinancing of debt incurred in building a power

generator a decade ago is saving the city as much as $7 million a year

in interest.

“Those

are huge savings for the city,” says Ward 9 Ald. Jim Donelan, who sees

the mayor’s handling of CWLP as one of Langfelder’s biggest

achievements.

The

refinancing came after Langfelder pushed rate restructuring through the

city council with little advance warning to the public. It was a

fundamental shift for ratepayers, who previously could count on saving

money if they conserved energy. Under the new rate structure, which

boosted the flat monthly charge while lowering the per-kilowatt usage

charge, large consumers of electricity can save money while small

residential customers pay more.

Langfelder

got it through the council on an 8-1 vote (Ward 5 Ald. Andrew Proctor

voted no, McMenamin voted present) just two weeks after it was publicly

announced. Opponents who pointed out that the new plan created a

disincentive to conserve power barely had a chance to squeak. The mayor

prevailed after meeting with aldermen in ones and twos, prior to the

proposal’s public debut, to pitch the plan that helped convince rating

agencies that the city was serious about righting CWLP’s listing

financial ship.

To

some degree, Langfelder benefited from events beyond his control. Before

leaving office, his predecessor, Mike Houston, predicted that CWLP was

about to turn a corner due to plummeting coal prices and low interest

rates that set the stage for refinancing. But McMenamin, who criticized

the mayor for fast-tracking the rate restructuring plan, praised

Langfelder.

“He got it

done,” the alderman says. Langfelder isn’t shy about taking credit.

“It’s 100 percent,” Langfelder boasts. “I don’t like to be cocky. I’m

not sure that we would have the…(bond) underwriter’s rating if I wasn’t

sitting in this chair.”

On

the campaign trail, Langfelder said that he favored CWLP getting into

solar energy and pointed to Springfield, Missouri, where the public

utility generates electricity with solar panels. But the city council

this year rejected the mayor’s request for $1 million to develop a

solar-energy facility. Today, he doesn’t sound nearly as cocksure about

solar energy as he did while a candidate. He mentions the city building

its own wind farm and talks about solar only when a reporter brings it

up.

“I think you have

to have the blend (between solar and wind),” Langfelder says. “If we’re

going to have renewable, I think solar’s a way. At least, take a look at

it.”

Focus and the future

Donelan,

who was a top aide to former Mayor Tim Davlin before becoming an

alderman a year ago, says that it’s easy for a mayor to lose focus.

“The

hardest thing for a mayor to do, because the job is 24/7, 365 days, is

to keep the vision,” Donelan says. “Administrative duties interfere with

that vision at times. And that’s why it’s good for the mayor to have

people both internal and external that he can bounce ideas off.”

Ward

8 Ald. Kris Theilen praises Langfelder as a mayor who returns calls and

is willing to listen. While some aldermen have grumbled about

communication, and the mayor admits screwing up by not giving the

council early warning about the Salvation’s Army’s proposed move to

Gold’s Gym, Theilen says that communication is a two-way street.

“We

don’t have to wait for him to come to us, we can come to him, too,”

Theilen says. “He’s very approachable. He’s willing to listen. … The

prior mayor was my-way-or-thehighway. The current mayor is more open to

suggestions.”

While

city posts are officially nonpartisan, city hall has a history of

politics that can split on party lines. Theilen, a Republican, says that

he hasn’t seen that from Langfelder, who is a Democrat.

“From

the day I met Mr. Langfelder, there has been a mutual respect,” Theilen

says. “The letters in front of the name have never mattered. It’s never

been about parties.”

While

Donelan warns that it’s easy for a mayor to get bogged down, Langfelder

insists that he’s got plenty of vision. Free WiFi, he promises, will

soon be operational in downtown. He talks about Hunter Lake and a

residency requirement for all city employees. Neither of those goals, he

predicts, is going to happen soon. Both, he says, are part of “the last

bite.”

“That’s why we’re taking our time, trying to move everything in place,” Langfelder says.

He sounds like a guy who’s already decided on a second term. Langfelder doesn’t deny it.

“I will go for a second,” the mayor vows.

“You never know. It could be two, it could be three.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].