State prison reform plan held captive

It’s called RANA and its impact could be significant. But only if Illinois’ Dept. of Corrections unshackles the program, a Rescuing Illinois report reveals.

PRISONS | Kari Lydersen

Illinois’ devastated finances and well-known government dysfunction is claiming another victim – the legally mandated launch of a promising prison reform program designed to significantly reduce the number of inmates returning to state prisons, according to a Better Government Association Rescuing Illinois investigation.

The Illinois Crime Reduction Act of 2009 ordered the state’s Department of Corrections to start a program dubbed “Risk, Assets and Needs Assessment” (RANA), which was to be implemented statewide by 2013.

So far, neither the full program nor a small proposed pilot program have started, despite a class action lawsuit demanding it get underway and the ongoing pleas of prisoner advocates, including the John Howard Association. The Illinois Department of Corrections (DOC), which has said the plan was tabled for budgetary reasons, notes that litigation is underway and declines to say when or if the RANA pilot program will proceed.

“This is not just an idea, this is law, but it’s not being adopted and implemented,” said Bob Kreisman, an attorney and member of the Union League Club of Chicago, which adopted a resolution in February calling for RANA’s implementation. “RANA is just a small piece but maybe this is part of the impetus to make changes in a criminal justice system in utter disarray and in great need of reform.”

RANA seeks to predict if newly released prisoners will return to prison by determining, and evaluating, the risks they pose along with their personal “assets” and “needs.” Assets would include a prisoner’s education level and family support, while needs can include mental health care and substance abuse treatment.

Advocates say that understanding and quantifying many of these factors will aid the state’s effort to reduce recidivism, a term used to describe the widespread and expensive problem of released prisoners quickly reentering correctional facilities.

One way to cut down on recidivism is by providing outgoing inmates with access to government-backed social services and support programs that can improve their transition to society, and RANA data can help make that connection, backers say. The data can also be used to match prisoners with the right programs and services while in prison, which could also benefit them once they are released.

And RANA results would also help the state parole board determine if longincarcerated elderly prisoners should be released, they add.

Attempting reform

The Crime Reduction Act notes that, “the Illinois correctional system overwhelmingly incarcerates people whose time in prison does not result in improved behavior.”

It

calls for changing this situation through evidence-based programs,

including RANA, to collect data and then use that information to make

better determinations about how to help prisoners succeed when they

reenter society.

In

2010, as the law demanded, a RANA task force was convened with the

assistance of the New York-based Vera Institute of Justice. Among other

things, the task force examined specific tools, or metric systems, that

were being used in other states. Illinois decided to use a tool known as

SPIn, for Service Planning Instrument.

Former

DOC acting director Gladyse Taylor tried to implement RANA with

existing staff, but the time demands were too great and her staff was

also concerned about not having the specialized skills necessary to

carry it out, she explained in a July legal deposition related to the

class action lawsuit filed against DOC.

About

400 new staff would need to be hired to implement RANA statewide,

Taylor said in the deposition. With the state’s severe financial crisis

and growing deficit, that has not happened.

Advocates

said they were told this summer that all DOC programming decisions were

on hold until Gov. Bruce Rauner named a new acting head of the

department. He did that on Aug. 14 by naming John Baldwin, former head

of the Iowa corrections department, who must still be confirmed by the

state Senate.

Advocates waiting and unhappy

Nonetheless,

prison reform advocates have grown increasingly frustrated with the

delay and with what they say has been a lack of information from DOC

about the program’s status.

Jennifer

Vollen-Katz, executive director of prison watchdog John Howard

Association, said that the group had not been able to get information

from DOC about the status of RANA, though she is hopeful that things

could change with the department’s new leadership.

“Our

understanding is it’s just not happening,” said Vollen-Katz before

Baldwin was named director. “There’s a vacuum at the top in terms of

getting information.”

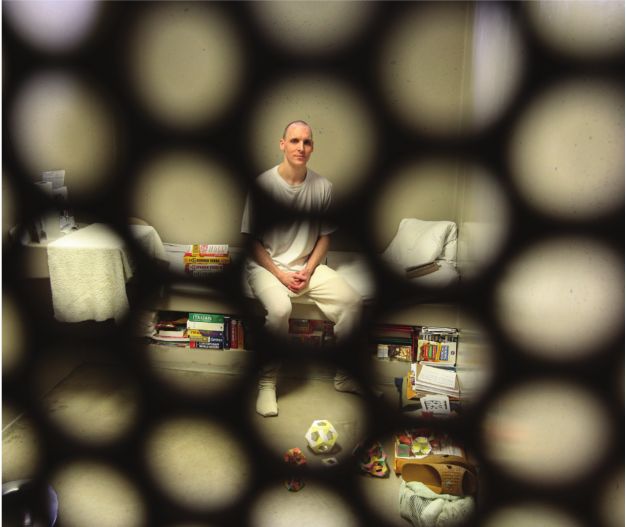

Moreover,

attorneys for a group of elderly prisoners known as “C-numbers” are

especially eager for RANA to be implemented, because they think it would

mean many of these estimated 170 prisoners being released after serving

what advocates say are disproportionately long sentences.

In

January, the Roderick and Solange MacArthur Justice Center based at

Northwestern University School of Law’s Bluhm Legal Clinic and the

Uptown People’s Law Center filed a class action lawsuit on behalf of the

“C-number” prisoners, demanding that RANA be implemented and that the

prisoners get new parole hearings using the data compiled under it.

The

“C-number” inmates were sentenced before 1978, before major changes in

Illinois’ sentencing structure and a system of defined sentences was

adopted.

They were

given “indeterminate” sentences of a wide range of years, with the idea

that a parole board would eventually decide when they were ready to be

released. As a result, C-number inmates continue to go before the

state’s Prisoner Review Board periodically, and the board votes on

whether to release them.

“When it was indeterminate you got a sentence of life or 200 years but the expectation was that a parole board would determine when you’re rehabilitated and let you out,” said David Shapiro, staff attorney of the MacArthur Justice Center.

However, the board typically votes not to release the prisoners, advocates say.

They

contend the board is not making its parole decisions based on objective

criteria, and that the prisoners have served significantly more time

than people sentenced today for similar offenses.

And

as the prisoners are aging and in many cases sick, their advocates also

say they pose little risk to society and their health care, and related

costs, places a significant burden on the corrections system.

There

is no guarantee that RANA would do anything to speed the release or

change the situations of these prisoners, experts say. But the C-number

prisoners’ attorneys think that objective data would make such a strong

case for their release, in many cases, that the review board would have

trouble saying no.

Pilot program grounded

Gladyse

Taylor, who became senior advisor to Acting Director Baldwin after his

appointment, has long been seen as an advocate of RANA. Last winter, she

spoke to the Union League Club of Chicago about the program’s merits.

As

state funding seemed unlikely, Taylor secured a $3 million, three-year

federal grant that should enable the department to run a pilot RANA

program, hiring seven new specialists.

With

no funding from the state necessary, that program was scheduled to

start in October, Taylor said in the July deposition. She said she

planned to post positions for seven new hires in August. The DOC

declined to respond to a question about whether the pilot program is

still scheduled for October.

Taylor said in her deposition that the pilot RANA program would include assessments for all C-number prisoners.

The

pilot would also target prisoners scheduled for release to seven

Chicago communities that are responsible for 40 percent of the people

ending up in the Department of Corrections, according to the deposition.

Some

are hopeful that under Baldwin, the corrections department will finally

institute the RANA pilot. With 35 years of corrections experience,

Baldwin is known as something of a reformer with a dedication to data

and evidence-based practices.

State Corrections tumult

However, DOC has had its share of management upheaval over the years and various inmate programs have come and gone.

Baldwin

is the second acting director named by freshman Gov. Bruce Rauner,

whose first acting director, Donald Stolworthy, left after only a couple

of months on the job.

The

corrections system is rife with operational and budgetary challenges.

The prisons, designed to hold 32,000 inmates, actually incarcerates

about 48,000 inmates.

In

February, a BGA Rescuing Illinois report found that the corrections

agency racked up a whopping $320 million in staff overtime and other

compensation over a fiveyear span, a finding that sparked Rauner to propose adding 450 new guards in his initial state budget.

More money needed

While

the pilot program is already funded, the legislature would need to

approve funds to expand RANA statewide. That would mean millions of

dollars the state does not have on hand.

In

fact, Illinois doesn’t even have a budget, although its fiscal year

ended June 30, and it is locked in a partisan fight to pass a spending

plan.

Still, advocates are holding out hope that the funds for bringing RANA statewide will be found.

Alan

Mills, executive director of the Uptown People’s Law Center, says if

the pilot program is implemented, the road will be paved for full

implementation.

Should

the court decide in the plaintiffs’ favor in the class action lawsuit,

which deals only with C-numbers inmates, the same legal arguments could

be made to demand statewide application, he said.

Kari

Lydersen is a Chicago-based author and freelance writer who writes

about government, criminal justice and public policy issues for the

Better Government Association and other media outlets. She can be

reached at info@ bettergov.org.