Extinct

What would be lost if the Illinois State Museum closes

STATE | Scott Faingold

There’s more to the Illinois State Museum than meets the average citizen’s eye. The exhibits on display at the museum’s main location at Spring and Edwards streets represent a tiny fraction of the riches maintained by the ISM. Few are aware that the staff of passionate, knowledgeable scientists who work at the museum’s Research and Collection Center (RCC) at 11 th and Ash streets will also be out of work if Gov. Bruce Rauner’s plan to close the museum is put into action. Such a closure could devastate a world-renowned research facility as well as an economic boon to the community in the form of jobs created through sizable National Science Foundation grants. The grants are in addition to the millions in tourist dollars generated by the museum proper.

A hearing about the potential shuttering of all of the facilities in the ISM system – including the Dickson Mounds Museum in Lewistown, the Lockport Gallery in Lockport, the Southern Illinois Artisans Shop and Southern Illinois Art Gallery at Rend Lake, and the Illinois Artisans Shop and Chicago Gallery in the James R. Thompson Center in Chicago in addition to the museum and RCC – was held before the Commission on Government Forecasting and Accountability (COGFA) July 13. Wayne Rosenthal, director of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources which administers the museum system, laid out the governor’s case for closure. “The budget structure greatly reduces available options to reduce spending to balance the budget,” Rosenthal said. “While the museum budget may seem small at $6.2 million, its budget is one-sixth of the general revenue funds received by IDNR.” During the hearing, State Representative and COGFA member Elaine Nekritz pointed out that the information provided to the commission by IDNR was “really slim.” She said that there was no evidence of consideration of loss of grant moneys and no indication of economic impact studies on the communities affected – all information required by statute in these kinds of hearings (and which have been provided by IDNR in previous facility-closure situations). Many of Rosenthal’s statements at the hearing were met with incredulous laughter or cries of consternation – sometimes both – from the capacity crowd. By contrast, a statement from the Springfield city council in opposition to closing the museum, read aloud by Mayor Jim Langfelder after Rosenthal’s unceremonious departure from the proceedings, was met with cheers and applause.

One proposal reiterated multiple times by Rosenthal was the plan to maintain a “skeleton crew” of three people to care for collections across all sites in the ISM system. A recent visit to the RCC indicated that such a crew would be faced with a monumental task.

According to museum director Dr. Bonnie Styles, the RCC does tremendous numbers of public programs, workshops and hands-on activities. There are currently 13.5 million objects in its collection, representing art, Native American heritage, ethnography, botany, geology, zoology and more. The museum is one of very few federally accredited curatorial facilities. “Collections are the core of our research, exhibition and educational programs – that’s what makes us a museum,” according to Styles. “People ask why we have so many specimens. The collections are comparable to a library or an archive. We have people who can read these objects like regular people read books. They have expertise. They can really read the history or the story of the object.”

The 97,000-square-foot former tax processing center has been in use as the Research and Collections Center since 1989, when it was renovated to become what Styles says is “one of the premier collection facilities in the country.” According to Styles, the RCC brings in around $2 million in grants each year from groups like the Institute of Museum and Library Services, National Science Foundation and National Endowment for the Humanities .

Osteology

One of the major laboratories in the facility is the osteology (bone study) lab run by Dr. Terrance Martin, chair of anthropology. “It’s a very specialized lab,” he says, “one of the most used labs in the Midwest. It contains a comparative collection used to identify remains.” He goes on to explain that it is an unusual lab in that it

keeps material from mammals, birds, reptiles and fish all in one place.

In a traditional setup there would be a separate lab for each category.

“You never know what you’re gonna get in a bag of animal bones from an

archaeological site,” he says. The day we visited, a group of students,

there on a twoweek National Science Foundation “Research Experience for

Undergraduates” grant, were working on ecological studies of fish. They

were busily utilizing collections stored along the walls of the lab. For

instance, if they came across a fossilized bone fragment and could at

least tell it was from a medium or mid-size specimen, they would simply

walk across the room to consult what amounts to a physical database of

modern remains which they are able to physically compare to the fossils.

“People

say, ‘Couldn’t you computerize this somehow?’” says Martin. The problem

is, researchers need to be able to do things like turn the bone over

and look at the other side. Does it have cut marks on it? Is it burned,

is it weathered? “These students are learning that you can’t just do

this from a book. We use the modern to help identify the old.”

Archaeology

The

archaeology collection is the largest collection at the RCC by far with

8.5 million specimens, including items such as a cedar carving possibly

of a Mississippian priest-chief’s face. “With items made of wood, if

you had fluctuating humidity it would start to crack,” says Styles.

Temperature and climate control would be among the many thousands of

tasks that would fall to Rosenthal’s proposed skeleton crew in the event

of closure. Also part of the archaeology collection is a fragment of a

skirt that Styles personally excavated in the lower Illinois valley. “We

found four big fragments of it and we think it is a woven skirt. This

is about 1,500 years old – it’s true weaving, over one, under one – made

with plant fibers. It’s a beautiful piece.” The fragment was in fact

the model for the skirt seen in the woodland diorama in the popular

Peoples of the Past exhibit at the ISM. “In fact, that exhibit is based

on my research that was done for my dissertation,” Styles says. “A lot

of our research is directly translated for the public in our exhibits. I

think we’re one of the better museums in the country for doing that.”

On

a more directly practical level, the RCC is keeper of the statewide

site file, mandated under the IDNR’s own Archaeological and

Paleontological Resources Protection Act. “We are the official

repository of artifacts and paleontological remains,” says Styles. There

are 66,000 sites, all in a geographic information system database.

“When there’s a construction project, a team goes out, and if they find

sites they send their paperwork here and all of it is entered into this

giant database. It is a very important function.” And another that would

apparently be carried out by the IDNR’s proposed skeleton crew of

three.

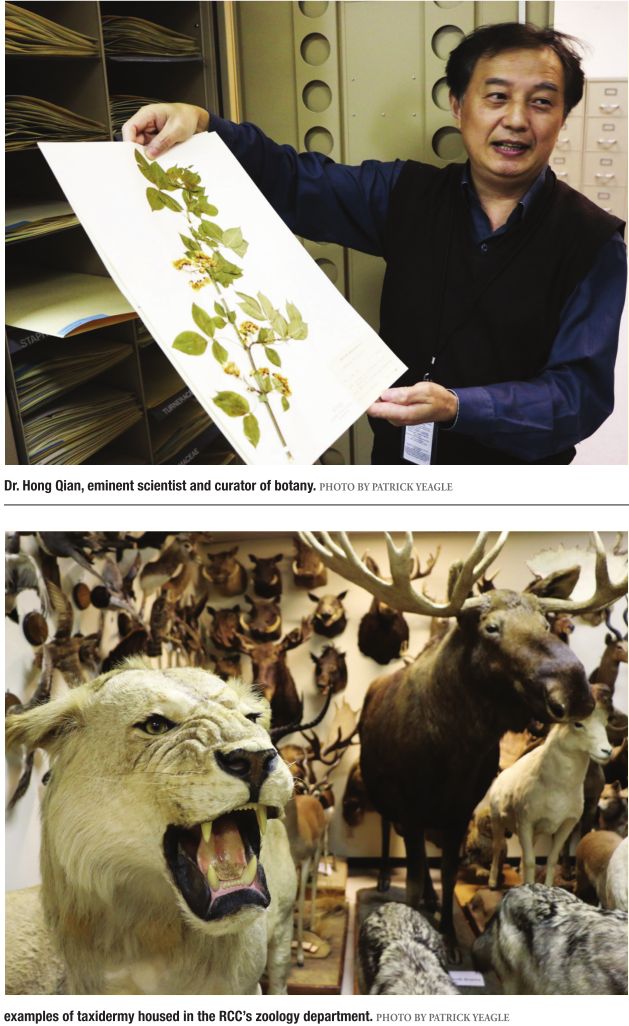

Zoology

In

the zoology department, Dr. Meredith Mahoney, who holds a Ph. D. in

Evolutionary Biology, Systematics and Zoology, is using the entomology

collection for her current research on great spangled fritillaries as

well as studying the Hines Emerald dragonfly. She describes the

dragonfly as the only federally endangered dragonfly species. At one

point it was thought to be extinct but was eventually rediscovered in

northern Illinois. In a theme that repeats throughout the visit, one

reason Mahoney gives for keeping samples over time is that new

technologies allow researchers to gather new kinds of information from

old samples – such as DNA extraction – which the original collectors or

donors would never have dreamed of doing.

The

ISM often takes in “orphan collections” from closed museums and

similarly the zoology and ornithology departments have often received

donations from sources such as family taxidermy hobbyists, a popular

pastime at the turn of the 20 th century. In addition to elephant bones,

and things like taxidermic walrus, warthog and grizzly bear remains,

the zoology department also has a large collection of mollusks. “We

don’t discriminate against invertebrates,” says Mahoney. The department

keeps a record of mussel species as the Illinois River changes,

comparing fossils to current information and the archaeological record.

Paleontology

Over

in the paleontology department, Dr. Chris Widga of Springfield,

associate curator of geology, is involved in research on the Tully

Monster and various other projects. However, preservation and care for

the huge collection of prehistoric fossils is at the forefront of his

mind. “Every paleontological program has a backlog of things that have

not even been prepped,” he explains, introducing volunteer Steve Morse,

who is working on fossils that came to the ISM from the U of I Natural

History Museum in Urbana when it closed in 2002. These fossils were

excavated in the 1950s and never fully prepared, repaired or stabilized.

Morse comes in for four hours every morning to prepare these specimens.

“He seems to like it a lot,” says Widga, and this is a good thing. “We

don’t have the hard-money staff to do these kinds of activities. I do

them as I can but Steve’s been really good at coming in and working away

at the backlog.

“We’re

trying to slow down the time it takes for these fossils just to totally

turn to dust,” Widga continues. “Controlling environmental conditions

is part of it but this is another part – constant repair and

stabilization have to go on.” For example, he shows us a mastodon tusk,

which had been on display for years and is now in a state of disrepair.

Through time, the expansion and contraction of the tusk itself was

different than a plaster plug in the interior of the tusk, and the plug

eventually burst through.

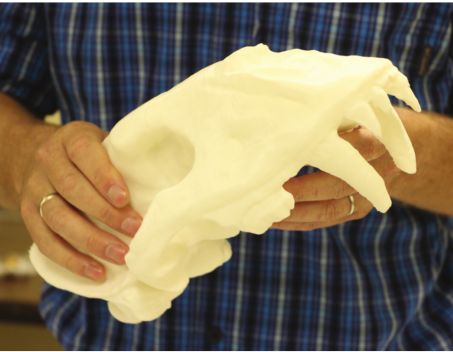

Widga

is also involved on the higher-tech side of the RCC with the ISM

advanced imaging lab which includes 3-D scanners and 3-D printers. “One

of our goals is to make our collections and our research as accessible

as possible,” he explains. “One way is to go online. Over the past two

years we have scanned more than 200 specimens.” These are

three-dimensional scans of fossils which will eventually be available

for anyone to download and make prints of themselves. Widga showed us

“prints” of a shark jaw, and a Tully Monster. Such reproductions are

useful for education and outreach. For one thing, unlike actual fossils,

they are not fragile and won’t shatter if dropped by an overeager grade

school student.

Botany

Dr.

Hong Qian of Springfield is curator of botany for the ISM and has

received a National Science Foundation grant to study invasive plant

species. “These exotic species are a problem not just for the U.S.,” he

explains. In Illinois, he says, every fourth species is invasive. “In

this state we have more than 1,000 exotic plant species.” Most of these

species are from China and Japan, where they only distribute in small

areas although here they are widespread. “One theory is that in their

native place they have natural enemies that don’t exist here.” The

objective of Qian’s work is to help find ways to control this harmful

plant life and he contends that the potential savings of successful

research are far more than the cost of the research itself. “If we can’t

take care of these things now, in the future we will be blamed,” he

says matter-offactly.

Qian

(pronounced chee-an) is an eminent scientist with 108 scholarly

publications to his name – more than 80 percent of these in

internationally recognized scientific journals. “Every day I am invited

to review papers by others but I have to turn them down, otherwise I

cannot do my research,” he says.

Qian

recently applied for what he describes as “nearly $1 million” in grant

money from the National Science Foundation – but he is acutely aware

that if the museum closes, this funding will not happen. News of the

potential closing has already been reported in many science journals,

which may cause the museum’s researchers to be turned down for any

funding currently pending. “If the museum is going to be closed, why

would they fund us? This research is comparing Asia and North America in

order to preserve both. But if the museum closes, that’s it. A big

loss.” Qian points out that the ISM is a job creator: if his most recent

NSF grant were to come through he would be hiring seven people to carry

out the work, employees who would be paid not by the state through the

DNR budget but with the federal grant money. According to Styles, there

are many local jobs generated through grants and other “soft money”

brought in by the RCC.

Neotoma database

Some

of the most crucial work at the facility is currently being carried out

by Dr. Eric Grimm, the museum’s director of science and chair of

botany, and his Neotoma Paleoecology Database, which acts as nothing

less than the infrastructure for global change research into environment

and climate. The NPD is a vast archive of all kinds of fossil data –

fossil pollen, fossil mammals, fossil lake algae, fossil

microcrustaceans, fossil insects, geochemical data – from lakes and

excavations. The data tell us about past environments through organisms

and plants, according to Grimm. “Ten thousand years ago what was the

environment like? It was very different from today. It provides that

kind of information.”

Another

important purpose, and a source of funding in many past years is what

Grimm calls proxy climate data. “The instrumental record [on climate]

only goes back 150 years in North America so if you want to study past

climate this is the way. Pollen falls in lakes, sinks to the bottom and

is fossilized.” The lakes in northern Illinois have been here for

between 16,000 and 18,000 years, and this provides a continuous record

of vegetation and other life forms which is calibrated by taking

contemporary surface samples to reconstruct past climate. “Measures of

salinity in microorganisms gives indication of lake chemistry,” says

Grimm. “Lake chemistry tells us about drought cycles.” All of this data

generated by ISM scientists is freely available from the web at

www.neotomadb. org. Using Google Scholar it was found that 700 papers

have been written utilizing the database. Scientists can get data

directly from the site but an Application Programming Interface allows

those on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

website to interconnect with Neotoma (Latin for “packrat”). “Scientific

research is funded by public money and these data should be publicly

available. We are providing that access,” says Grimm.

Fine and decorative arts

The

RCC’s fine and decorative art collection is the “new kid on the block,”

according to art department chair Jim Zimmer. It started in 1926 with

items purchased from exhibitions, although more recently the majority of

the artwork comes from donations, including a recent gift of more than

500 quilts from a single donor. “These things come into our collection

because on an international level donors realize our commitment to these

collections – taking care of them, researching them and sharing them

with the public.” In addition to temperature and humidity concerns,

textiles must be folded carefully, and periodically refolded, to avoid

permanent creasing. “It’s not a matter of just throwing something in a

box and sticking it on a shelf, it requires constant care.” Future

skeleton crew members, take note.

Recently,

the RCC received a collection of artifacts from a single family who

relocated from the East Coast to Illinois in the early 19th century and

remained here for more than a century. According to Zimmer, the

collection tracks history through objects. “Just to see a family come to

Illinois in 1857 all the way to the 1970s – it’s a story in itself,”

says Angela Goebel-Bain, curator of decorative arts and history. Zimmer

goes on to explain that sometimes treasured objects family members are

fighting over will end up being donated to the museum as a resolution.

“ISM

is the only museum in the state that focuses exclusively on Illinois

art and artists,” says Zimmer. The art collection includes a wide

variety of dolls, fairy lamps and other decorative objects, which are

regularly lent out for display. “We have objects in the Governor’s

Mansion, State Capitol and other institutions,” according to Irene

Boyer, registrar for decorative arts.

“One

of the things I’m very proud of,” says Zimmer, “is that a lot of times

in institutions of this size you have curators who specialize in one

certain area. We don’t have that many curators so there is a lot of

interdisciplinary knowledge at work here. It would be difficult to

replace individuals who have that broad knowledge.”

Indeed,

for example, Styles, the museum director, has been with the ISM for 39

years, starting out as a curator in anthropology, while Zimmer has been

there for 23, beginning as an intern. “People spend a lot of time here

and become really familiar with the collections and the history,” says

Styles.

“One of the

things we focus on is collecting family stories associated with each

piece that comes into the collection,” says Goebel-Bain, who is

currently working on a World War II veteran’s uniform, which she calls

“the most complete uniform I’ve ever seen in my life, right down to his

gas mask.”

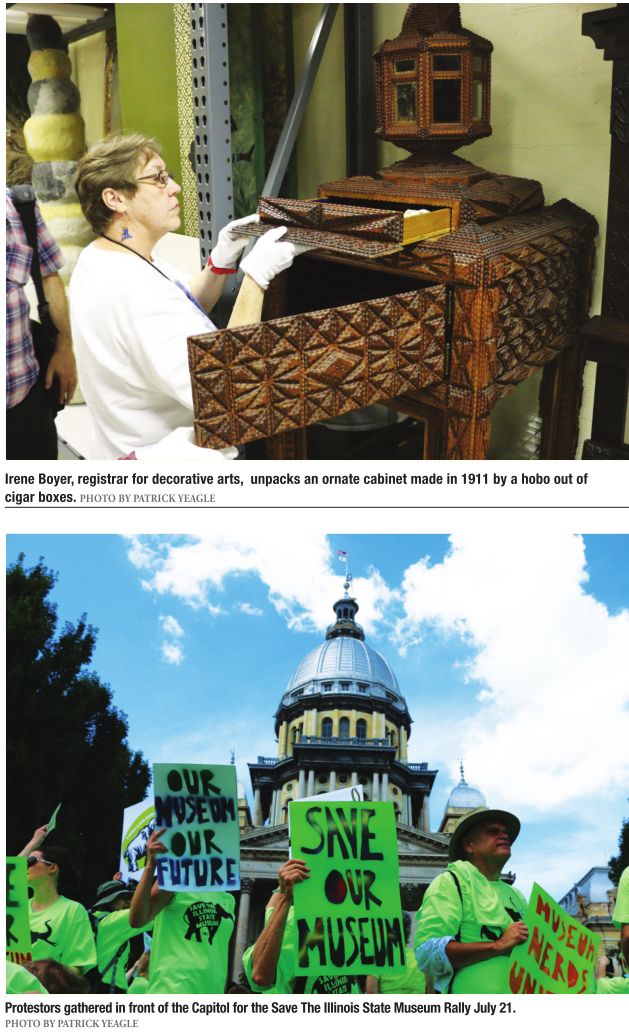

One

intriguing art department acquisition is a large and ornate cabinet in

the rarefied category of “tramp art,” a category of work wherein

itinerant people – often though not exclusively during the Great

Depression – would craft objects from cigar boxes. This particular item

is unusual due to its size and function, according to Zimmer, including a

space customized to specifically fit a Sears crystal radio as well as a

detailed and enclosed crucifixion diorama and hidden drawers and

compartments.

The

artisan was a hobo named Julian Spurmont (names are often lost) who was

moving through Illinois from Canada and stopped at a farm in Kankakee in

the early winter of 1911. He agreed to build the large, ornate cabinet

out of cigar boxes in exchange for a winter’s room and board. “He and

the farmer he stayed with would go to taverns regularly to collect more

cigar boxes,” says Angela Goebel-Bain, adding that this greatly angered

the farmer’s wife, according to their son who donated the piece.

“If

you care about your family’s material at all you need to write it down

so that your grandkids and great-grandkids know what this is,” sighs

Goebel-Bain. “If the information gets separated from the object it’s

just meaningless old stuff.” A fate which may indeed await the vast,

impressive and important collections in the Illinois State Museum system

if Rauner’s plan for closure comes to pass.

Scott Faingold can be reached at [email protected].