Feral horses from western states come to Illinois looking for a new home

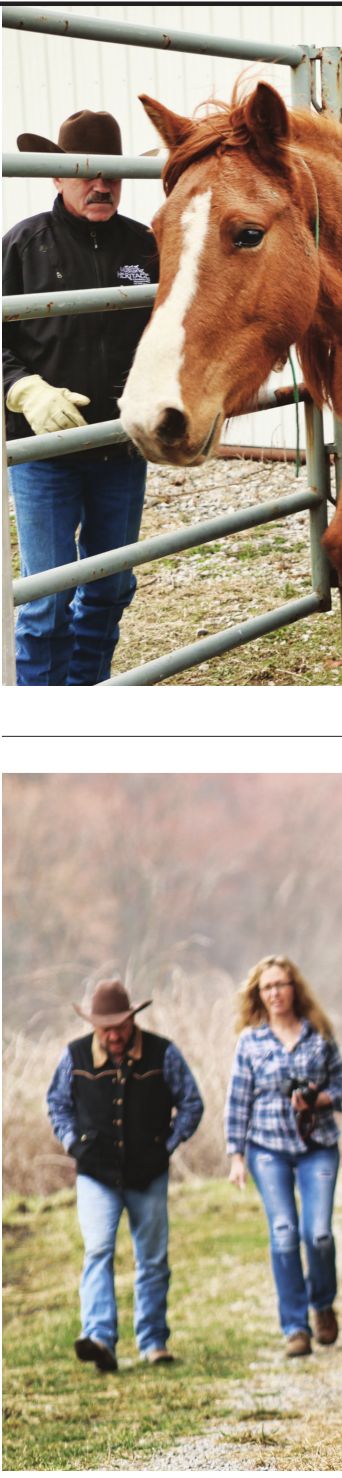

In a muddy corral on a hill in southern Illinois, dozens of horses chomp on hay and cautiously eye the cowboy-boot-clad visitors who walk past their pen. When a human gets too close, the horses draw their heads back behind the vertical bars for protection, but they’re in no danger. These horses are awaiting new homes after traveling hundreds of miles to Illinois.

They’re part of the federal Bureau of Land Management’s Wild Horse and Burro Program, which rounds up free-running horses from 10 western states and ships them east to adoptive owners. In late March, the program brought about 100 horses to Ewing, Illinois, marking the return of wild horses to Illinois at a facility shuttered six years ago.

They’re part of the federal Bureau of Land Management’s Wild Horse and Burro Program, which rounds up free-running horses from 10 western states and ships them east to adoptive owners. In late March, the program brought about 100 horses to Ewing, Illinois, marking the return of wild horses to Illinois at a facility shuttered six years ago.

All “wild” horses in the United States are descendants of domesticated horses brought here by Spanish explorers in the 16 th century. The modern horses are technically termed “feral” because of their domesticated lineage, and American feral horses are known as mustangs.

Ewing hosts a federally run horse facility that was closed in 2009, according to Steve Meyer, supervisory program specialist with the bureau. Although the facility was closed, the bureau continued to send horses there for periodic adoption events, the last of which was in 2013, Meyer said. Ewing is set to reopen as a holding facility for the horses, he said, so not all of the horses transferred to Illinois will be adopted right away.

The Wild Horse and Burro program began in 1971 in response to growing herds of unmanaged horses roaming the American west. Today, the program draws horses from 10 states like Nevada, California and Utah, preventing the herds from growing so large that their habitat can’t support them. By putting the horses up for adoption to qualified owners, BLM ensures they won’t be euthanized or sold to “kill buyers” like slaughterhouses.

The minimum cost to adopt a mustang is $125, although bidding for the horses can mean a higher price. Meyer says he came to love horses at age 16 when he worked a summer job at a race track. He owns five horses himself and has spent 15 years with BLM’s wild horse program.

“What’s not to like about horses?” he said.

“There’s a bond with wild horses that you can’t get with a domestic horse.”

Meyer explains that feral horses have learned to be self-sufficient, so they see humans as predators.

“Once you get to where they trust you,” he said, “the bond is much stronger. Once that animal goes from fearing you to trusting you – you can ask any one of these people – it’s probably one of the greatest feelings in the world.”

Anne Corbin, who owns Marion Horse Center in Marion, Illinois, adopted a chestnut mustang with a blond mane at the event. Corbin affectionately refers to her as “boss mare” for the horse’s assertive personality. Although the horse was only adopted on March 20, Corbin was able to ride her within two days.

“These horses just haven’t

been around people, so when I have a horse that’s gentled, she

understands the relationship between a human and a horse,” Corbin said.

“They know to be gentle with a human. I should be able to have a horse

that’s a partner and remove their doubt and uncertainty.”

Corbin’s

impressive “gentling” – a verb that has replaced “breaking” when

referring to wild horses – is part of the Extreme Mustang Makeover, a

competition in which horse trainers adopt feral mustangs and domesticate

them in just 100 days. The Mustang Heritage Foundation, a Texas-based

nonprofit focused on promoting mustang adoption, partners with the

Bureau of Land Management to host the competition and other programs

around the nation. Corbin and other adoptive owners will take their

horses to St. Louis on July 10 and 11 to be judged by how well the

horses accept direction and maneuver an obstacle course.

Barbara

Montgomery, a volunteer with the Indiana-based Hoosier Wild Mustang

& Burro Association, says when she trained her first wild mustang,

it was almost “anti-climatic.”

“I

thought, ‘I’m going to really test myself; I’m going to get a mustang,’

” Montgomery said. “It was totally the simplest horse I’d ever worked

with. Within a few days, I was already brushing her and had a halter on

her, leading her around. I’ve just found that a lot of them are that

way.”

Montgomery says mustangs are easy to train because they don’t have the baggage of abuse that some domestic horses have.

“They’re

a blank slate,” she said. “They’re a blank canvas, and whatever you

come up with is part their personality and part what you put in.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].