My New Year’s resolution: No more healthy, sort of

FOOD | Julianne Glatz

This column started out as a rant. For a while now, I’ve wanted to bang my head against a wall almost every time I hear the adjective “healthy.” So I decided my 2015 New Year’s resolution would be that I will no longer refer to specific foods and eating practices as healthy. In truth, it’s not going to be a hard resolution to keep. I’ve been eschewing the term “healthy” for some time.

“But what’s wrong with saying something is healthy?” you may well ask.

The problem is that “healthy” has been so overused and misused that it has become meaningless. Worse, designating something as healthy causes some folks to think that the more of it they eat, the healthier they will be. Industrial food producers love to label their product healthy (or subtly imply that it is) when it has some nutritious components even if it most of its calories come from nonnutritious ingredients. That whole grain cereal may have lots of fiber, but check out its sugar content. I love my wholesome, homemade granola chock full of nuts, oats, millet, flax seed, dried fruits, nuts, honey and olive oil; I could happily munch on it all day. But if I did, I’d be consuming many times more calories than I should.

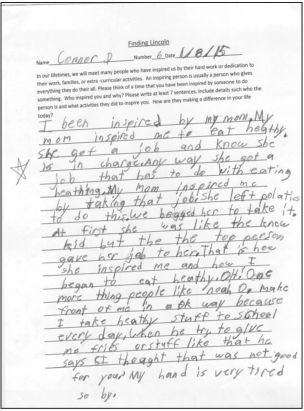

I was stopped mid-rant by a Facebook posting of 8-year-old Connor Dillman’s school essay about someone who inspired him: his mom, Jennifer Dillman. She is the executive director of GenH, a fantastic organization dedicated to promoting healthy kids through education, exercise and eating habits.

For Connor, what constitutes “healthy” is simple: it’s not junk food. And for kids, that’s probably definition enough. But his essay also made me concerned that by decrying “healthy” I might be offending the folks at GenH (it’s short for Generation Healthy), for whom I have boundless admiration.

Thankfully, my worries were groundless.

“Actually, we try not to use “healthy” around here anymore,” Jennifer Dillman told me. Their reasons for avoiding it are the same as mine. That’s why GenH has taken “Eat Real” as their slogan.

Over the last several decades, “healthy” for many people became synonymous with anything low or non-fat. But natural fats contain important nutrients. Parents who took low or non-fat as an absolute found that if they put their infants on such a regimen, the babies suffered brain damage. Manufacturers of processed foods replaced fat in their products with salt, highly refined sugars and carbohydrates. And Americans just kept getting unhealthier.

Probably no one has studied the issues of American eating culture and food production, from industrial farming and processing to sustainable practices, more extensively than Michael Pollan. In his 2006 book, Omnivore’s Dilemma, he describes America’s “national eating disorder,” saying it would not have happened in a “culture in possession of deeply rooted traditions surrounding food and eating.”

Pollan continues:

A country with a stable culture of food would not shell out millions for the quackery (or common sense) of a new diet book every January. It would not be susceptible to the pendulum swings of food scares or fads, to the

apotheosis every few years of one newly discovered nutrient and the

demonization of another. It would not be apt to confuse protein bars and

food supplements with meals or breakfast cereals with medicines. It

probably would not eat a fifth of its meals in cars or feed fully a

third of its children at a fast-food outlet every day….

I

wonder if it doesn’t make more sense to speak in terms of an American

paradox [rather than national eating disorder] – that is, a notably

unhealthy people obsessed with the idea of eating healthily.

Lurching

from one dietary extreme to another and radically changing scientific

and pseudoscientific recommendations make many folks just give up. High carb! Low carb! Eggs are bad! But wait, egg whites are OK! No, whole eggs are good! Deciding what and how we should eat seems hopelessly confusing. But is it really unfathomable?

“No,” says Pollan in his 2009 book, Food Rules, an Eater’s Manual:

A

few years ago, feeling as confused as everyone else, I set out to get

to the bottom of a simple question: What should I eat? What do we really

know about the link between our diet and our health? I’m not a

nutrition expert or a scientist, just a journalist hoping to answer a

straightforward question for myself and my family.

Most

of the time when I embark on such an investigation, it quickly becomes

clear that matters are much more complicated and ambiguous – several

shades grayer – than I thought going in. Not this time. The deeper I

delved into the confused and confusing science, sorting through the

long-running fats versus carbs wars, the fiber skirmishes, and the

raging dietary supplement debates, the simpler the picture gradually

became.

….for the Nutritional Industrial

Complex

[our] uncertainty is not necessarily a problem, because confusion is

good for business: The nutrition experts become indispensible; the food

manufacturers can re-engineer their products (and health claims) to

reflect the latest findings and those of us in the media who follow

these issues have a constant stream of new food and health stories to

report. Everyone wins. Except, that is, for us eaters.”

As

a journalist, I fully appreciate the value of wide-spread public

confusion: We’re in the explanation business and if the answers to the

questions we explore got too simple, we’d be out of work. Indeed, I had a

deeply unsettling moment when, after spending a couple of years

researching nutrition… I realized that the answer to the supposedly

incredibly complicated question of what we should eat wasn’t so

complicated after all, and in fact could be boiled down to just seven

words:

EAT FOOD. NOT TOO MUCH.

MOSTLY PLANTS.

There

it is: a seven-word definition of healthy. But I’m still going to avoid

using “healthy” because it means so much more and so much less to so

many people. Incidentally, Pollan’s Food Rules breaks down those

seven words into 64 simple rules, most no more than a sentence long,

some with an explanatory paragraph. Examples are “Eat well-grown food

from healthy soil,” “Avoid food products containing ingredients that no

ordinary human would keep in the pantry,” and “Eat slowly.” It’s a slim

volume well worth having.

Included

in the rules are “Treat Treats as Treats” and “Break the Rules once in a

While.” Should folks never let a French fry or doughnut pass through

their lips? Of course not. The flip side of “healthy,” and equally

head-banging worthy, is the term “heart attack on a plate.” But there is

no such thing. No single food or meal, whether it’s a huge steak and a

loaded baked potato with onion rings, a massive Springfield horseshoe or

an ice cream sundae is going to cause a heart attack. They’re not even

unhealthy – as long as they are an occasional indulgence. When Pollan

was a guest on NPR’s “Wait, Wait Don’t Tell Me,” he related standing in

line at a grocery store with a box of Froot Loops cereal. The person

behind recognized him, “Oh, ho! So that’s what Michael Pollan really eats!”

the guy said. But the cereal wasn’t for Pollan. His child had a “thing”

for Froot Loops and was allowed to have a bowl of the artificially

colored, high sugar cereal on Saturdays – a treat rather than an

everyday breakfast.

What’s

unhealthy is when too many calories – especially calories with few or

no nutrients – and are from highly refined, processed ingredients

comprise most or all of someone’s diet.

As

another highly respected food writer, Michael Ruhlman said recently,

“When you’re cooking and eating, you need to use all your senses. And

the most important is common.”

Contact Julianne Glatz at [email protected].