Illinois’ broken tax system

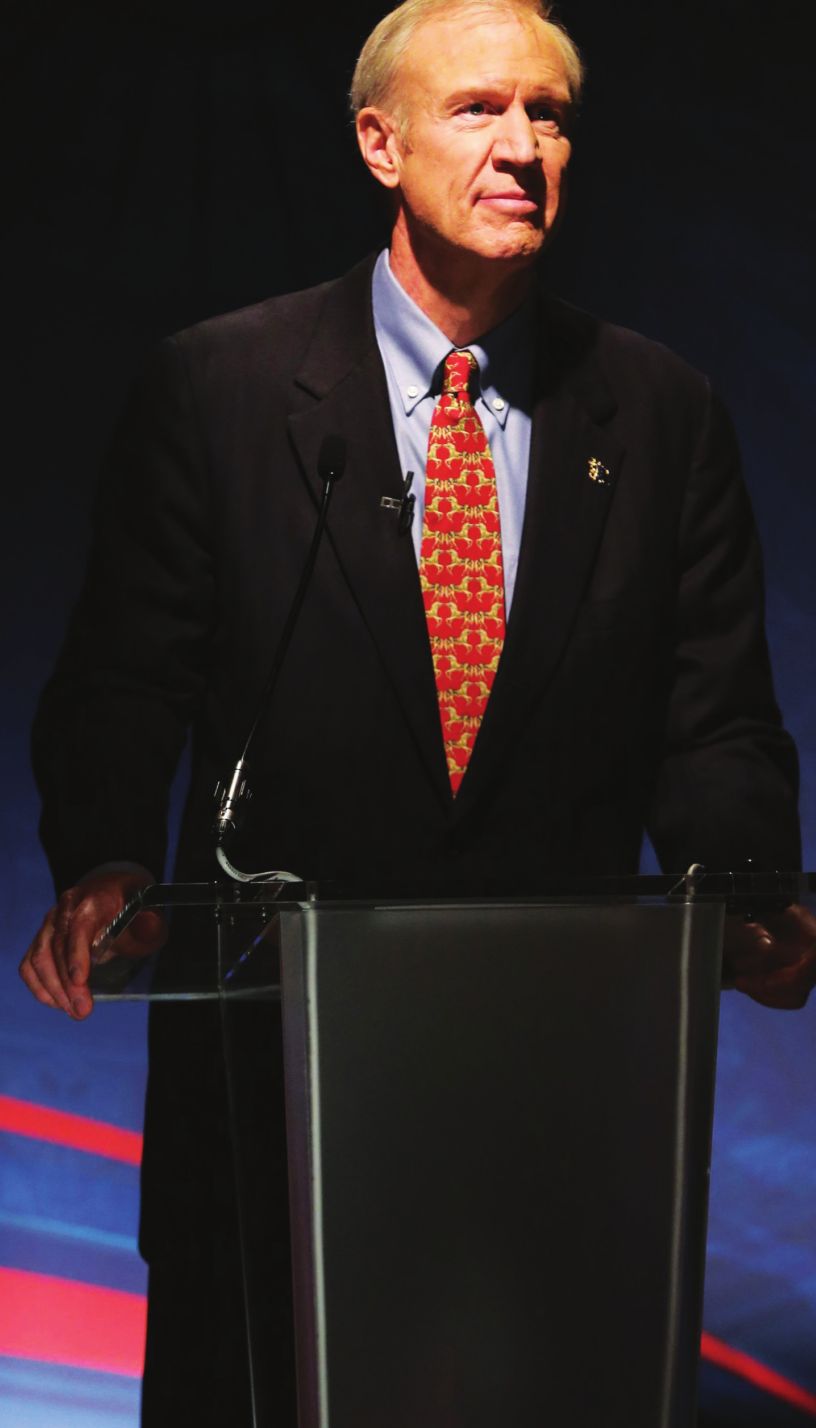

Can Rauner fix it?

POLITICS | Bruce Rushton

Governor-elect Bruce Rauner said all the right things while not saying much during a December speech in Springfield filled with generalities and rah-rah talk.

We need a tax code overhaul and long-term structural change to eliminate budget deficits. Forget about politics, I’m going to do what’s right and get the state’s financial house in order.

“We’ve got big changes, a bold agenda coming,” Rauner vowed during his Dec. 16 speech at the Sangamo Club. “We’ve got to do what’s right for the long term. … Every generation is better off in Illinois than the last generation – that’s always got to be our guiding principle.”

Rauner, due for swearing in on Jan. 12, disavowed any political ambitions beyond a second term.

“I will be willing to serve for eight years if people want me,” Rauner told the crowd at a luncheon sponsored by the Better Government Association. “Getting re-elected is not on my top 10 worry list. … I ain’t doing this because I want to run for higher office – my wife would shoot me if I ran for higher office.”

In the event he was protesting too much, Rauner could do worse than fix the state’s finances if he wants a springboard to the White House.

Despite a 66-percent income tax hike that took effect in 2011 and expired on Jan. 1, state government has been operating at a deficit. When pension obligations are factored in, Illinois ranks fifth in the amount of per capita debt, with the state owing nearly $25,000 for every man, woman and child who lives in the land of Lincoln, even though per capita revenue in the state’s general fund increased from $1,748 in 2009 to $2,817 in 2013, a jump of more than 61 percent. The state’s backlog of unpaid bills, which stands at more than $5 billion, could reach as high as $20 billion within three years, depending on which expert you ask. The state’s credit rating is the lowest in the nation.

In short, Illinois is the nation’s poster child for fiscal irresponsibility. Rauner hasn’t said just what he’ll do to put the state on the road to prosperity, but he has made a lot of promises, including vows to improve schools and maintain social services.

“We can judge ourselves as a community by how well we take care of our most vulnerable citizens,” Rauner said last month. “We can’t pay for it unless we’re a booming economy – pro-business, pro-growth, pro-free enterprise, pro-investment, pro-career creation, not just job creation.”

It sounds Reagan-esque – improve the business climate and the state’s financial woes will solve themselves. It’s not so simple, of course, as Rauner

himself acknowledges. Without providing details, he says that state

finances need long-term structural change, and taxes are a big part of

it.

“I want us to have

a reasonable tax burden,” Rauner told his audience. “We don’t have to

have the lowest taxes in America. But we need to be competitive on our

taxes and we need to grow our way out of our problem.”

Politics and tax codes

The fiscal mess Rauner faces is brutally summed up in Fixing Illinois, a

2014 book by James D. Nowlan, who is a former legislator and University

of Illinois political science professor, and J. Thomas Johnson, former

director of the state Department of Revenue and president emeritus of

the Taxpayers’ Federation of Illinois.

Between

2002 and 2011, the state each year spent $7 billion more than it took

in, Johnson and Nowlan write. The state’s net assets during that period

declined from an abysmal -$5.7 billion (yes, negative) to -$42.5

billion. To stay afloat, the state has borrowed and sold long-term

assets such as future proceeds from lawsuit settlements with tobacco

companies.

The

personal income tax that fell from 5 percent to 3.75 percent on Jan. 1

has left a $4 billion hole in the state budget. Thanks to a tax code

only Rube Goldberg could love, schools rely on property taxes – the

second-highest in the nation behind New Jersey – the way that

photosynthesis relies on sunlight. Some taxpayers are squeezed while

others get free rides. Big corporations need only huff and puff about

moving outside Illinois to get tax breaks. People living in food

deserts, where fast food is more common than fresh fare, pay taxes to

eat while the wealthy dine on filet mignon from Whole Foods, where meat

is free of both antibiotics and taxes.

It

adds up to the fourth-most regressive tax code in the nation, according

to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, a nonpartisan

research group based in Washington, D.C. In thundering against the

status quo, Rauner has raised expectations in a state that has

traditionally seen tax hikes and overhauls when Republicans occupy the

governor’s office and Democrats control the legislature. If nothing

else, Rauner is doing a good job of convincing folks that the state is

in fiscal crisis, which could set the stage for a true tax-code overhaul

as opposed to nibbling around edges.

“I

think there’s great potential for governorelect Rauner in his first

budget to set forth a path for the state that will move the state

forward and stabilize it,” says Laurence Msall, president of the

Chicago-based Civic Federation that has recommended keeping the income

tax at 5 percent for another year to avoid a disastrous fiscal cliff.

“Having watched the state of Illinois now for almost three decades, the

reality is, the financial condition of the state continues to decline

and in recent years it’s declined at a faster rate than anyone has seen

before.”

Ralph

Martire, executive director of the Center for Tax and Budget

Accountability in Chicago, says that he’s in a wait-and-see mode.

“I

think governor-elect Rauner really has an opportunity to lead on a

bipartisan basis and put the state on sound fiscal footing,” Martire

said. “Or he can continue to rail against politicians that have been in

Springfield forever, and blah, blah, blah. If he takes that latter

approach, I don’t see how things can get better.”

Kent

Redfield, political science professor emeritus at the University of

Illinois Springfield, sees at least an opportunity for real change in

the tax code.

“I think Rauner can sell this,” Redfield said.

“We’re

already hearing rhetoric that the sky is falling, and it is. … He’s got

a situation where, if he can pull a rabbit out of a hat, he can present

it as, ‘This is the only option.’” Whatever it is he tries, Rauner

can’t do it alone. He’ll need help from the legislature, but history

suggests that lawmakers’ necks aren’t at risk. Just ask Charles Wheeler,

a University of Illinois Springfield public affairs professor who has

studied what happened to legislators who voted in favor of establishing a

state income tax in 1969 as well as lawmakers who voted for tax hikes

since then. More than 90 percent were re-elected. Indeed, five

Republicans who voted against establishing an income tax lost bids to

keep their seats in the ensuing election. By contrast, no Democrat who

voted in favor of collecting an income tax lost re-election bids,

underscoring the power of a legislative district map drawn so in favor

of incumbents that it is practically impossible for lawmakers to lose

their seats based on a single vote, Wheeler says.

It’s different for the chief executive. Gov.

Richard

Ogilvie, who championed the institution of an income tax, called

himself “the governor with guts” during his failed campaign to win a

second term in 1972, when his opponent successfully blasted him on tax

issues.

Rauner, who

has famously promised to shake up Springfield, said last month that he’s

not afraid to take the heat, and he’s been talking to legislators.

“As

many of them said, ‘So long as you take the arrows and the heat, we’ll

take the votes to get you most of the apples,’” Rauner said. “I’ll take

all of the heat. I’ll take all of the arrows. Blame me. I’ve got no

problem with that. I just want the solution. That’s all I care about.”

Shaking up – or down – retirees

Outside

the Capitol dome, there’s widespread agreement on what constitutes

fair, progressive tax policy and what does not. No state does it

perfectly, which is to be expected given politics, but there are lots of

states that do a better job of levying taxes than Illinois.

Regardless

of how much Rauner cuts the state budget, and it’s a safe bet he’ll be

in a cutting mode, even the most strippeddown, bare-bones government

costs money.

Nonpartisan

experts agree that the best way to raise revenue is via a broad tax

base that spreads the load as equally as possible – instead of making

one group of people pay relatively high taxes to raise a given amount of

money, it is better to have a larger group of people raise the same

amount with each person paying less. Rauner has said so himself.

“Yes,

we do need tax overhauls,” the governor-elect told reporters after his

Sangamo Club address. “A growth tax code has a broad base and low rates.

… The key is, we (must) have a competitive tax code and it’s progrowth

while also providing sufficient revenue to fund needed services.”

Then the governor-elect undercut what he had just said.

“As

I’ve said, I’ve had no plan to tax retirement income,” Rauner said. “I

said that during the campaign, and we’re sticking with that.”

It’s

a stunning position for a politician who insists that he doesn’t care

about re-election and says that his guiding principle is ensuring that

every generation is better off than the last generation.

Illinois

stands nearly alone in its refusal to tax retirees. The irrationality

of exempting retirees from income taxes is underscored by the fact that

just two other states with income taxes do it to the same extent as

Illinois, which is leaving as much as $2 billion of potential tax

revenue in the hands of retirees. And the figure will only grow as the

baby-boom retirement wave crests.

The

Civic Federation says that the state left nearly $44 billion in

retirement income untaxed in 2011. The vast majority of that total, more

than $30 billion, was income in excess of $50,000 per year.

The

inequity is staggering. Someone who earns $40,000 a year in adjusted

gross income while raising a family and making mortgage payments in

Illinois would pay $1,500 a year in state income taxes at the present

tax rate of 3.75 percent. A retired millionaire with no mortgage or kids

to feed pays nothing on income derived from pensions, individual

retirement accounts, 401(k) plans and Social Security.

The

Center for Tax and Budget Accountability says the state in 2008 would

have collected nearly $1.3 billion from filers with more than $50,000 in

retirement income taxed at a 5 percent rate. Furthermore, the group

says, more than 80 percent of retirees wouldn’t pay anything if there is

a $50,000 exemption. The Civic Federation points out that the potential

tax base from retirees is growing at a much faster rate, 6.5 percent

annually, than the existing tax base from those still in the workforce,

which is expanding at just 1.9 percent each year. Bottom line, Rauner

could provide a substantial tax exemption to retirees, thus softening

political backlash from a demographic that votes, while still raising

sufficient revenue to make tax relief possible for those in the

workforce.

If Rauner

won’t listen to the Civic Federation and others who agree that Illinois

should start taxing retirees, then he should look at Indiana, Wisconsin,

Michigan and other states he sees as competitors and role models. They

all tax retirees. Unlike Illinois, they also have graduated income taxes

and taxes on services and other things that progressives and

nonpartisan experts say makes for a fair tax code.

Rauner

claims to have an open mind. “I’m not a shoot-the-messenger guy,”

Rauner told the Sangamo Club crowd. “I love people who tell me I’m

wrong, tell me I’m missing an opportunity and respectfully disagree with me. I don’t have all the answers. I’m wrong a lot.”

Can

Rauner deliver on vows to improve education and provide adequate social

services while keeping the income tax rollback, exempting all

retirement income and ending the state’s sorry tradition of deficit

spending?

“That dog won’t hunt,” Martire says.

Spreading the pain

Illinois’

tax base is too narrow, nonpartisan experts agree, and that’s not good

for either taxpayers or the state, which suffers from a revenue stream

that isn’t as diverse as it could be.

If

one part of the economy lags, retail sales for example, another that

isn’t suffering so much, the service sector for instance, can help ease

the financial blow to government coffers in states with broad tax bases.

But not in Illinois, which doesn’t collect taxes when lawyers provide

advice, mechanics fix cars or plumbers stop leaks. While other states

apply sales taxes to such services – and dozens upon dozens more –

Illinois does not, and so the state puts the fiscal burden on consumers

of goods, which are taxed upon sale, instead of those who purchase

services that are sold tax free.

How

much the state could raise by taxing services depends on which services

are taxed and by how much, but Moody’s estimated it could be as much as

$7.3 billion in a 2010 report commissioned by the Commission on

Government Forecasting and Accountability, a bipartisan panel of

lawmakers.

“A services

tax is aimed at drawing revenues from some of the state’s

fastest-growing and most dynamic industries and relieving some of the

burden from historically strong but contracting industries such as

manufacturing,” Moody’s analysts wrote in the report. “Fears that

services taxes will push away critical industries may be misplaced;

other states with strong financial and corporate headquarters industries

such as South Dakota and Delaware also heavily tax services.”

Democrats

in Illinois have proposed service taxes without success. To his credit,

Rauner has proposed taxing some services, but he doesn’t seem keen on a

wholesale approach. Both the comptroller’s office and

Moody’s have said that the state could bring in more than $7 billion by

taxing services, but Rauner during the campaign threw out a figure of

$600 million and suggested that services from architects, accountants,

engineers and other professionals should be exempt as well as more

ordinary services provided at barber shops, animal care facilities, day

care centers and Laundromats.

That

leaves open the question of what income taxes do, but it could be

challenging in Illinois given that it would require an amendment to the

state constitution, which now mandates a flat-rate tax.

In

a 2012 report, the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability says the

state would get at least $2.4 billion in new revenue by taxing the

wealthy at a higher rate than other taxpayers. Properly designed, the

center says, a graduated income tax could cut income taxes services,

exactly, Rauner expects to tax. Regardless, talk of a sales

tax on services counts as progress.“That’s a major step toward

modernization,” says Martire, noting that the service sector accounts

for more than 60 percent of the state’s economic activity. “You just

can’t leave the largest and fastest growing segment of your economy out

of the equation and expand your tax base. It’s not like it would make us

an outlier.”

“I just want the solution. That’s all I care about.”

The Center for Tax

and Budget Accountability also supports a graduated income tax code with

rates that increase with income levels. That’s what most states with

for taxpayers who earn less than $150,000 while keeping the income-tax

burden for millionaires below 5 percent.

Not

everyone thinks it’s a good idea. Rauner has said he’s against it, and

Nowlan and Johnson in their book call for sticking with a flat income

tax. In any case, there is widespread agreement that income taxes are

about as fair as taxes can get.

“You

get a raise, you pay more,” Martire says. “It’s the only tax that

automatically adjusts based on your ability to pay. It’s the fairest tax

we have.”

Rauner has

said that he favors sticking with the rollback that has dropped the

income tax from 5 percent to 3.75 percent. The Center for Tax and Budget

Accountability argues in favor of a 5 percent rate. The Civic

Federation recommends keeping a 5 percent rate in place for one year

while lawmakers craft a long-term plan to stabilize the state’s

finances.

Martire,

Msall and Rauner agree on at least one thing: Property taxes are far too

high. Martire says property taxes, adjusted for inflation, have risen

at a rate 20 times higher than median incomes during the past two

decades. It is, experts agree, largely a byproduct of a state so

strapped that it can’t properly fund education and so the burden falls

on homeowners.

Rauner

vows to freeze or cap property taxes, but that would still leave

Illinois with astronomical real-estate taxes compared with the rest of

the nation. And it’s hard to imagine how property taxes could be frozen

while providing Rauner’s promised improvements to education if state

funding for schools isn’t increased.

By

creating diversified revenue streams and ending tax breaks, Nowlan and

Johnson figure that the state could take in nearly $11.8 billion more

than it is now, a veritable waterfall of cash that would soon have the

state solvent. It wouldn’t be painless, however. Nonprofit organizations

would have to start paying sales taxes, for instance, and some retirees

would have to pay income taxes.

If

the state extended the sales tax to groceries, it would take in as much

as $1.5 billion a year, Nowlan and Johnson say. Poor people who receive

food stamps wouldn’t get hit, and the state could soften the blow for

the working and middle class by providing limited income-tax exemptions

to make up for taxes paid on food.

Bad

as the state’s finances are, Martire says the state can pay its

past-due bills and become solvent if politicians make tough choices and

modernize the tax code.

“Or

we could remain a virtually bankrupt state, running deficits year after

year,” Martire says. “I think it’s pretty clear which option we should

choose if we have adults in the room.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].