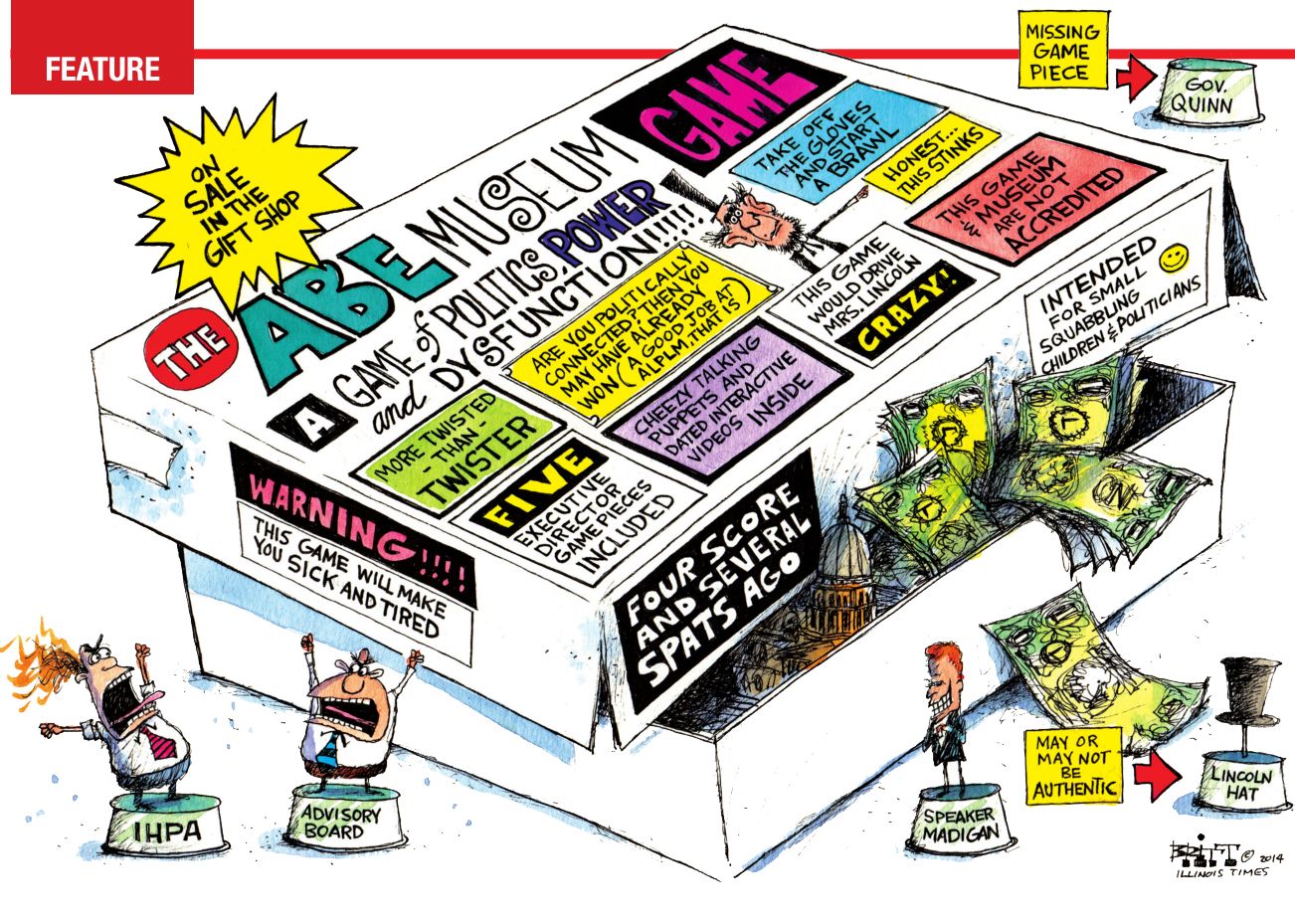

Board games

Who should control Lincoln’s museum?

GOVERNMENT | Bruce Rushton

Steven Beckett pleads naive.

When he drew up a bill to divorce the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum from the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, the University of Illinois law professor who chairs an ALPLM advisory board says he had no idea that he was an architect of uproar. The bill would give Beckett’s advisory panel control of the institution, including the power to hire and fire the executive director, who now serves at the pleasure of the governor.

It wasn’t a power grab, Beckett insists. Both Beckett and members of his advisory board say the current governance structure makes no sense, and the result has been battles between boards and bureaucrats. While boards bicker, the directors of the IHPA and ALPLM have been fighting over who has the power to run the institution.

With power at stake and House Speaker Michael Madigan front and center, it’s not surprising that cynics would say that this is just another politics-as-usual gambit. Naysayers have pointed out that the speaker, who has sponsored Beckett’s bill, is a friend of ALPLM director Eileen Mackevich, who is a frequent companion of Stanley Balzekas, Jr., who owns the Chicago building where the speaker has an office.

“Half of me goes, ‘Boy, that was stupid, Beckett – you should have anticipated that this will become all about the speaker and Illinois politics,’” Beckett said shortly after the legislative session ended with his plan stalled in the Senate. “ ‘Now this idea that you had is in this big murk. It advanced nothing.’” On the other hand, the future of Springfield’s biggest tourist draw is now on the radar screen of most everyone who matters in the General Assembly, which Beckett points out isn’t necessarily a bad thing. His plan landed, or crashed, just one week before adjournment, a seemingly out-of-nowhere bill sponsored by Madigan, a man accustomed to getting his way. Except this time he didn’t. And the bill wasn’t out of nowhere.

Emails between players show that Madigan’s interest in who calls the shots at ALPLM goes back at least eight months, when friction between Mackevich and Amy Martin, her putative boss who heads IHPA, was heating up, with who’sin-charge-here a common refrain. Mackevich comes off as an idealist and would-be visionary who wants to reorganize staff and spend money on consultants to improve operations. Faced with to-the-bone budget cuts, Martin seems a resigned pragmatist as she reins in Mackevich.

“There is a fight before us…to keep our doors open,” Martin told Mackevich in an April 9 email sent in response to the ALPLM director’s plea to spend $32,000 or so on consultants to review library operations and recommend improvements. “Please understand all else needs to be put on hold.”

At the time, IHPA was facing cuts that have become reality in a spending plan that is more politics than math, with legislators expected to revisit the state’s finances after Election Day. Martin apparently didn’t realize that a presidential library putsch was in the works. But her boss, Gov. Pat Quinn, did, or at least should have. After all, emails show that Sean Vinck, the governor’s chief information officer, was in the loop.

“What’s the status of the bill?” Vinck asked Mackevich in an email sent May 23, hours before Madigan introduced the bill that has sparked an unusually public spat over the destiny of ALPLM and IHPA.

Later

that same day, after the speaker introduced legislation, Beckett told

members of his board that Vinck had helped him as he drafted the bill

sponsored by the speaker.

“I

have worked with Sean Vinck to put the idea of separating the agencies

into legislative form,” Beckett wrote in an email to advisory board

members.

In an

interview, Beckett says that he consulted Vinck while drawing up the

bill, but the governor’s aide never took a position, and Quinn has

professed himself neutral. Meanwhile, Madigan’s bill, drawn up largely

by Beckett, surprised several members of the advisory board, prompting

criticism of Beckett by colleagues who learned about the legislative

push from the media.

“I

was a little disappointed that the discussion didn’t actually start

with the board which is charged to deal with the issue,” advisory board

member Richard Craig Sautter told Beckett during a board meeting last

week.

There is plenty

of acrimony between the advisory board, which has no power other than to

make suggestions, and the IHPA board, which oversees the institution

and makes final calls on such matters as what items will be loaned and

contracts with vendors. Patrick Reardon, a retired Chicago Tribune writer

who serves on the advisory board, went so far as to use the B word

during last week’s board meeting when Martin said that the IHPA board

planned to form a committee to address governance issues.

“Isn’t this like asking Blagojevich to investigate himself?” Reardon asked.

“This is outrageous!” someone snapped in response amid loud gasps and murmurs.

Dysfunction reigns, and the gloves are off.

The

legislature, if not the governor, is the closest thing to a referee,

but neither Quinn nor the General Assembly has come up with a solution.

The

bill that would put Beckett’s advisory group in charge of ALPLM sailed

through the House, but Senate President John Cullerton wouldn’t call it

for a vote. No one, however, is calling the plan dead. After all, it

passed the House on an 84-29 vote, with 20 Republicans voting in favor.

Local legislators were split, with Raymond Poe, R-Springfield, voting no

and Rich Brauer, R-Petersburg, voting yes.

Brauer

said he’s concerned about hiring and voted for the separation in hopes

that a standalone institution would make better employment decisions.

“Right

now, it’s very political,” Brauer said. “And I know they are putting

people in positions in historic preservation that have no historic

preservation background – it’s just political placement. … I think it’s

important that we take the political influence out of the Lincoln

library and museum.”

Poe says the plan came up too late in the session to merit a yes vote.

“I’m

not sure if there’s something there or not,” Poe said. “Before we do

anything, I think we need some hearings. I’m not necessarily opposed to

it, I just need to know a lot more.”

Cullerton

has not rejected the idea of taking the presidential library and museum

away from the IHPA and making it a standalone agency. Indeed, he has

said that he believes the institution could flourish if it had more

independence, and he’s suggested putting it under the umbrella of a

university.

“It has gotten attention,” Beckett says. “It (Madigan’s bill) does have a chance to advance, even though it started out badly.”

Money, jobs and accreditation

Nearly a decade after it opened, the museum, while still a must-see for anyone interested in Lincoln, is showing signs of age.

Wearing

a suit and tie that looks a bit dated, Richard Norton Smith, the

institution’s first director who left for another job in 2006, stars in a

video that tells visitors the importance of the neighboring library,

where Lincoln’s papers are being digitized and meeting rooms are

equipped for videoconferencing. Tim Russert, the television newsman who

died in 2008, delivers a fictional news account of the 1860 presidential

election. Thomas Schwartz, who moved to Iowa in 2011, is still

identified as state historian in an “Ask Mr. Lincoln” interactive video

that could use a spruce-up, according to Mackevich, with new questions

and new technology so that the exhibit becomes more than a place for

visitors to rest their legs.

There

is a shortage of staff, particularly at the library. Four years after

the American Association of Museums, now called the American Alliance of

Museums, recommended that the library switch from microfilm to digital

equipment to preserve newspapers, the staff is still using microfilm –

Mackevich and IHPA spokesman Chris Wills point out that state law

requires microfilm. Then again, state law requires that the library

employ a facilities operations director but that position without a job

description has never been filled.

The

AAM also found problems in human resources, ranging from an abundance

of open positions to union rules that required time-strapped

administrators to carefully craft job descriptions to ensure that

positions would go to the best-qualified people instead of the union

member with the most seniority. The AAM also suggested restructuring

library staff to improve efficiency.

Four

years later, many of the same issues remain. ALPLM had had 75 full-time

employees in 2010, when the AAM said that vacant jobs were a concern.

With 63 full-time employees, there are a dozen fewer staff members

today. The institution has made little progress in taking steps to gain

accreditation aimed at ensuring that the museum follows best practices

in acquiring, preserving and displaying artifacts and documents. The

IHPA board has adopted no mission statement, no strategic plan, no

institutional code of ethics, no collection management policy and no

disaster response plan, all necessary elements of gaining accreditation.

“All

of those documents are important for museums to operate, whether or not

they are accredited,” says Karen Witter, former associate director of

the Illinois State Museum who is working as a consultant to help ALPLM

on accreditation issues. “They have only existed in draft form, and they

need to be formally adopted.”

Beckett

wants accreditation, and his board has been working on required mission

statements and policies. Due to a lack of library staff, Reardon says

that he and fellow advisory board member Paula Kaufman, University of

Illinois librarian who sits on the advisory board, drafted collection

policies themselves to help set priorities on what sorts of materials

the library should collect.

The library

isn’t just a Lincoln archive and repository. It also serves as the

state’s historical library, and so collects items that have nothing to

do with Lincoln. One sticking point in developing a collections policy

is deciding whether the library should actively seek to shore up

weaknesses, such as a lack of materials from the Great Depression and

World War II, or maintain the status quo. And, if there is a goal of

closing gaps, should the policy have fiscal teeth with a requirement

that a percentage of funds be used on improving areas deemed weak.

Work

on accreditation won’t matter if the IHPA board, which has to approve

required paperwork, doesn’t buy in. And the board has signaled that

accreditation isn’t a top priority.

Two

years ago, Sunny Fischer, IHPA board president, told her colleagues

that accreditation was important but not necessary for a worldclass

institution. Museum attendance has sagged from 600,000 in 2009, the 200

th anniversary of Lincoln’s birth, to a bit more than half of that.

About 50,000 people visit the library each year, according to IHPA

reports. Fewer than 3,000 are researchers, according to IHPA numbers,

and no one who visits the library is charged an admission fee.

Martin

has set a goal of raising annual museum attendance to 500,000.

Meanwhile, research positions at the library go unfilled. The IHPA

hasn’t had a state historian, who is assigned to oversee the library’s

research and collections division, since Schwartz left three years ago.

During a 2012 IHPA board discussion on accreditation and the lack of a

state historian, IHPA board member Daniel Arnold focused on numbers.

“Dan

Arnold stated that the ALPLM’s focus needs to be on attendance numbers

because they generate revenue,” according to minutes of the 2012

quarterly board meeting. “(He) stated that any use of funding that does

not improve attendance numbers should be secondary to raising attendance

numbers.”

Five ALPLM

administrators earn sixfigure salaries. Researchers with academic

backgrounds, however, are low on the financial ladder. Curator James

Cornelius, for example, earned just $47,316 last year, even though he

is, arguably, the most public face of the institution, having been

interviewed scores of times for television programs, newspaper stories

and magazine articles.

Cornelius

was granted a 32 percent raise in December but remains the second

lowest paid employee in the institution’s research and collections

division. In justifying the bump, Martin told Central Management

Services that Cornelius was “the premiere expert on Lincoln” and his

position required a doctor’s degree, yet he was one of IHPA’s

lowest-paid employees.

It

is against this backdrop that the IHPA is trying to hire a state

historian. Money for the position was approved in 2012, but the search

has not gone well. Just 10 people applied for the position this spring,

and only four met minimum requirements. The

salary is listed as “depends on qualifications” in a job description

that runs more than 800 words, with another 250 words spent on minimum

requirements that include everything from a driver’s license to the

ability to manage the research and collections division.

“The

job description would mean Jesus Christ would have to come down to

earth again,” says Richard Meister, an advisory board member who sits on

the search committee and sees the search as an example of dysfunction.

“I said from the very beginning we would not find candidates.”

Wills, however, says the job description was nearly identical when Schwartz and his predecessor were hired.

The

institution also lacks a director of exhibits and a director of

education, positions that Witter, the accreditation consultant, calls

“key.” She said that she has recommended the jobs be filled, and Martin

last week told the advisory board that candidates have been interviewed.

Growing tension

Amid

the staff shortage and lack of accreditation lies a rift between Martin

and Mackevich dating back at least nine months, when the IHPA director

said that she would take over planning for ALPLM’s approaching 10 th

anniversary observances.

“It

is clear that this is not a priority for you, but it is for the

administration,” Martin told Mackevich in an email last September.

Members

of Madigan’s staff and the governor’s staff were soon in touch with the

IHPA. Madigan’s staff asked whether Beckett’s group was the ALPLM’s

only advisory board; Martin had a conversation with Jerome Stermer, the

governor’s chief of staff. Just what they discussed isn’t clear.

“I

appreciate you taking the time to discuss ALPLM today,” Martin wrote in

an email to Stermer eight months ago, days before Madigan’s staff asked

about advisory boards. “Please know I have every intention of making

this situation work.”

One

month later, Mackevich received a legal opinion from Tom

Schanzle-Haskins, a lawyer in private practice, whom she had tasked with

telling her whether the IHPA director had authority to make decisions

for the ALPLM. The answer was no, according to Schanzle- Haskins – both

Mackevich, who serves at the pleasure of the governor, and Martin, who

is appointed by the IHPA board, report to the IHPA board, which is

appointed by Quinn.

“The

clear intent of the statute, from its plain language, is not to include

the Abraham Presidential Library and Museum within the jurisdiction of

the Historic Sites and Preservation Division of the agency,” the lawyer

wrote.

Martin, who

sounds like she thinks she’s the boss in emails to Mackevich,

subsequently got an opinion from Garth Madison, the IHPA’s general

counsel, and Quinn’s office informed her that the governor’s staff had

identified “errors and omissions” in Schanzle-Haskins’ analysis.

Last

December, the IHPA board talked about the need for an endowment,

perhaps as much as $1 million, when Beckett, accompanied by former U.S.

Sen. Adlai Stevenson III, told board members that the Stevenson family

wanted to donate papers dating to the 19 th century, with some items put

on display in the library.

The

proposed Stevenson gift has been a divider. Last September, Martin

complained that Mackevich had been meeting with Stevenson and Wayne

Whalen, chairman of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Foundation

that raises funds, about the proposed gift. She was upset that she

hadn’t been included.

“Her

actions are quite frankly reckless and my concern is how this

ultimately reflects on our credibility and reputation,” Martin wrote in

an email to IHPA chairwoman Sunny Fischer and Simone McNeil, then

operations director for Quinn who now heads Central Management Services.

“I’m concerned she’s making promises we cannot keep.”

Martin

said she was concerned about the cost of exhibiting the Stevenson gift.

Carla Knorowski, director of the foundation, also had concerns and sent

an email to Mackevich, but the contents were redacted in a copy

provided by the IHPA.

Despite

concerns, Beckett’s advisory board in March approved a gift agreement

and forwarded it to the IHPA board for final approval. Martin seethed,

telling Justin Cajindos, Quinn’s deputy chief of staff, that the IHPA

board would bypass Beckett’s board and negotiate directly with the

Stevenson family. She complained in an email that the advisory board had

ignored the IHPA board’s request to amend a draft agreement, and

Beckett had not allowed her to speak until the advisory board had

finished its discussion.

“It

is not likely the IHPA board will approve this agreement as it stands

in June,” wrote Martin, who told the IHPA board in prepared remarks last

week that the IHPA staff has “fine-tuned” the agreement scheduled for

consideration by the agency board on Monday, June 23.

Shortly after Beckett’s board approved the gift agreement, Martin was again battling Mackevich, who wanted to

reorganize the library staff that includes the collections arm of the

museum and also hire consultants to evaluate library operations and

suggest improvements. Back off, Martin ordered.

“I

must insist that you halt any activity to reassign or reorganize staff

and the organizational chart,” Martin wrote in an April email to the

museum director. “These are specific task (sic) of the HR division and

when communicating or redirecting bargaining unit employees you put the

agency at risk of a grievance if you do not follow the set guidelines

and rules set forth by the union.”

The library and museum, Martin warned, was facing cuts.

“I

want to be sure you fully understand the magnitude of the ‘Dooms Day’

budget that is currently be(ing) considered by the legislature and until

a budget is passed there is no certainty of how the ALPLM will be

affected,” Martin wrote.

By

then, Beckett had drafted a bill to separate the museum from IHPA. He

says that he gave the bill to Sen. Michael Frerichs, D-Champaign, and

the legislation was soon in Madigan’s hands. By early May, he and

Mackevich were meeting with the speaker’s staff.

Beckett

complains that the IHPA doesn’t allow the library enough autonomy. For

example, he says, the IHPA hired the institution’s chief of staff

without consulting Mackevich. Wills, however, says that Mackevich

interviewed Ken Crutcher, who worked as Springfield’s budget director

and as a state procurement officer before he became chief of staff last

year, before Martin sought authority from the governor’s office to hire

him.

“The final (hiring) recommendation would have been through Amy,” Wills said. “That does not mean that Eileen had no input.”

Advisory board members say that the IHPA too often throws cold water on advisory board ideas.

“We’ve

got some library people, we’ve got some lawyers, we’ve got some

writers, we’ve got some people with some real wide experience,” Reardon

says. “The IHPA always either drags its feet or says we can’t do

things.”

During last

week’s meeting, Meister, the advisory board’s vice chairman, criticized

Martin for requesting copies of advisory board meeting agendas before

they had been distributed. He held up a copy of the AAM’s 2010 report in

which outside experts noted staffing challenges presented by union

contracts and governance issues that included fuzzy lines of authority

between the IHPA board and the ALPLM’s private foundation tasked with

raising money.

“This has been four years that we’ve known,” Meister said. “We really have a very dysfunctional operation.”

Martin,

however, blasted Beckett during the meeting, calling the would-be coup

unprofessional and counterproductive. The ALPLM, the IHPA director said,

was working fine.

“We’re not aware of anything that’s broken,” Martin said.