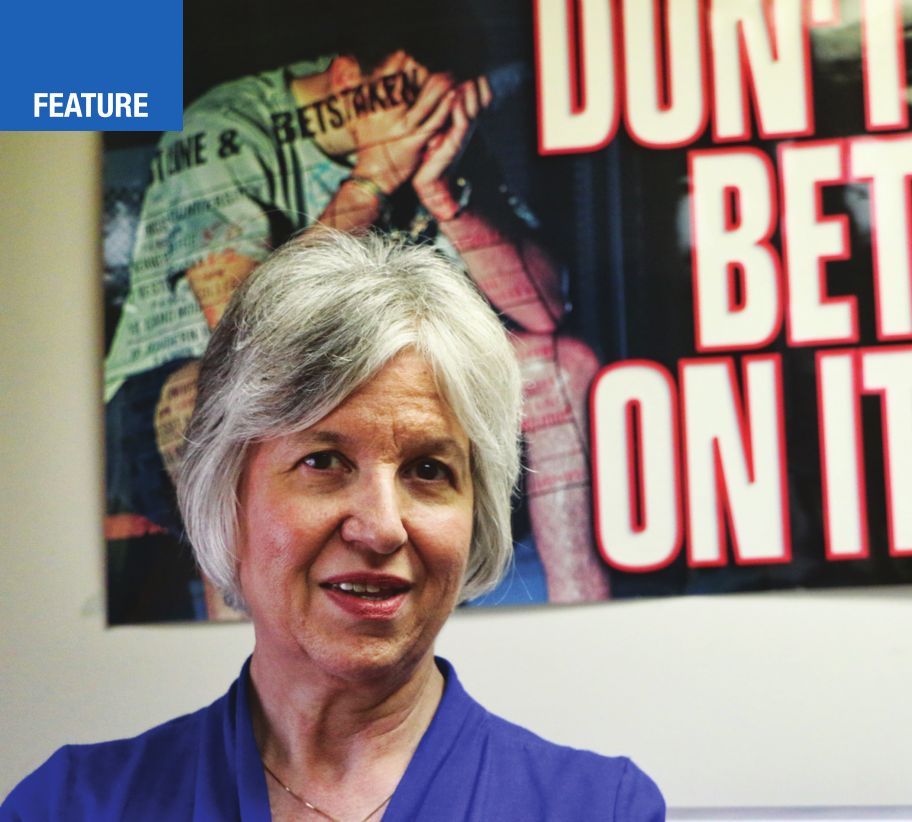

The church lady

Anita Bedell fights gambling and keeps the faith

ACTIVIST | Bruce Rushton

She’s almost always outgunned, outfinanced and outvoted, but it’s hard to imagine Anita Bedell getting outworked.

As executive director of Illinois Church Action on Alcohol and Addiction Problems since 1994, Bedell has been fighting the good fight for two decades, imploring governors and legislators to lower the blood-alcohol limit for motorists, curb gambling and resist a national trend toward legalizing marijuana. She has had her successes, but they are outnumbered by defeats, and hers has become a lonely battle. You don’t have to look any further than ILLCAAP headquarters on Jefferson Street to see that.

A gas station across the street sells beer and wine, thanks to a zoning change and liquor license granted by the city in 2008 over the protests of a dozen or so kids that Bedell brought to a city council meeting. A windowless adult video store less than two blocks away on Jefferson closed only recently.

“God has called you to faithfulness, not results,” reads a wall placard in the barebones ILLCAAP office. “Don’t measure the size of the mountain, talk to the one who can move it,” reads a desk ornament inscribed with the words of Max Lucado, a preacher and author of Christian-oriented inspirational books.

Carrie Nation she is not. While America’s most famous prohibitionist used a hatchet to get her point across, Bedell has relied on statistics and a calm, even voice during her career as the state’s best-known lobbyist against drugs, gambling and alcohol. From her sensible looks-like-Penney’s clothing to her to her aging Buick LeSabre sedan, she is straight from central casting. But books have more than covers.

“I think she’s dismissed as being, quote, the church lady at times,” says the Rev. Thomas Grey, who once lived in Illinois and is now a senior advisor for Stop Predatory Gambling, a nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C. “Anita is not the cartoon character that they want to make her out to be. You cannot

find her speaking an untruth in any testimony she’s ever made – everything is footnoted, everything is researched. To do that for over 20 years is a real credit to who she is. She does it because it’s the right thing to do.

“There aren’t many people like that.”

Commitments and changing times Bedell is loath to talk about herself.

She confesses that she has gambled herself, but only once, and the game she played, bingo, comes as no surprise. She is a teetotaler who drinks no coffee but plenty of tea. She plays piano and attends St. Joseph The Worker Catholic Church in Chatham, where she lives. When she isn’t testifying against bills to allow slot machines at the state fairgrounds or the state lottery on the Internet or new casinos, she says she likes to garden, read, cook and listen to music.

What kind of music? All kinds, she answers, without providing examples. She wasn’t always involved in politics. Before becoming an activist, Bedell, who is from Illinois, taught school in South Carolina when her husband was stationed there while serving in the military. She says she taught eighth grade and high school, but won’t say what subjects.

“I taught something,” she says. “I’d rather it (the story) be about the organization than me personally.”

In a that-was-then-this-is-now world where elected officials too often break vows on everything from tax hikes to limiting themselves to just a few terms in office, Bedell is both persistent and consistent. She remembers which lawmakers pledged not to expand gambling without a vote of the people in the 1990s, then voted for gambling bills that include legislation that has allowed video gambling machines in virtually any business that has a liquor license.

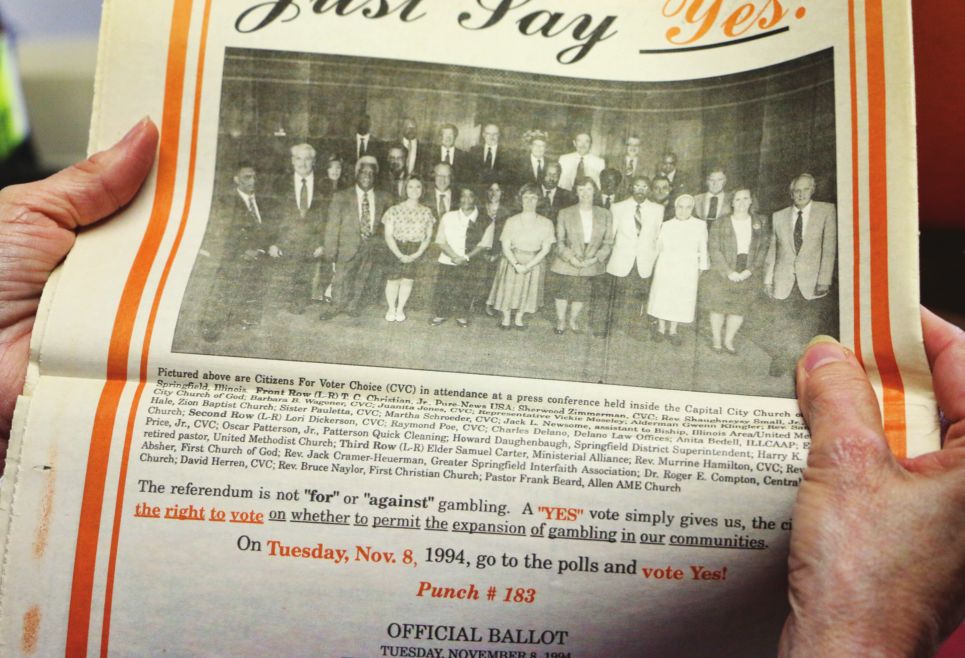

State Rep. Raymond Poe, R-Springfield, for example, posed for a photograph in 1994 along with Bedell and other backers of a referendum in which 90 percent of voters said they wanted an

election before any expansion of gambling in Sangamon County. At the

time, gambling proponents were talking about building a casino along the

Sangamon River.

By

the mid 2000s, however, Poe’s position had changed. He supported bills

to expand harness racing at the state fairgrounds while allowing more

off-track betting. He also favored slot machines at the fairgrounds, and

he made no apologies when Bedell called him out in the press, with the

legislator saying that economics had changed since county voters said

that they wanted to vote on any proposals that would expand gambling.

Constituents didn’t want gas, income or sales taxes raised, he said in

2008, and taxes on gambling promised a way to ease the state’s fiscal

woes. Since 2009, Poe has voted in favor of at least 10 pro-gambling

bills, by ILLCAAP’s count, and hasn’t opposed a single one.

“Was

it a lifetime commitment or was it a 1994 commitment for that year?”

Poe says today. “I didn’t vote for gaming for about 10 years – I think

that 10 years ought to be pretty good on a commitment.”

Poe

wasn’t the only local legislator who flipped on the gambling question.

During his first campaign for state Senate back in 1995, now-retired

Sen. Larry Bomke, R-Springfield, said that he was personally opposed to

gambling, but that voters should have a say in any proposal to expand

gambling. By 2012, Bomke was supporting a massive expansion of gambling

in Illinois, including slot machines at the fairgrounds, slots at

horse-racing tracks elsewhere in the state, five new casinos throughout

the state and expansions of existing casinos, all without a vote of the

people.

Bedell gives a sad smile while recalling the 1994 referendum that ended up making no difference.

“When

you get 90 percent of the people, that’s huge,” Bedell said. “They

(lawmakers) just ignored it. It’s disheartening, to tell you the truth.”

An

evolving mission Bedell, who had held a clerical position at St. Joseph

The Worker Church, took a job at ILLCAAP in 1990, the same year that

legislators approved the establishment of 10 casinos outside Chicago,

which remains offlimits to both full-blown casinos and video gambling

machines in bars and restaurants that now pepper the rest of the state.

ILLCAAP

considers itself a harmprevention organization and has a related

agency, Churches In Action, that is headquartered in the same building

and distributes anti-drug and alcohol literature to church and youth

groups. Unlike Churches in Action, ILLCAAP operates as a “social

welfare” organization under the federal tax code for nonprofits and has

more latitude to get involved in politics than its sister agency.

“I

had my degree in teaching,” Bedell says of her decision to apply for a

clerical position at ILLCAAP. “I thought I could use my background. It

was a good fit.”

Four

years later, she became executive director of an agency that celebrated

its 100 th anniversary in 1998. She has headed the organization longer

than any other person.

If nothing else, ILLCAAP has stamina.

It

got its start as the Anti-Saloon League of Illinois, back when William

McKinley was in the White House and “Remember the Maine, down with

Spain” was the catchphrase that helped light the Spanish-American War.

Meanwhile, movements for women’s suffrage and temperance were growing in

strength.

There was

big money and political influence in the no-booze movement as

Prohibition approached. William H. Anderson, a lawyer from Carlinville,

parlayed his position as head of the Illinois Anti-Saloon League at the

turn of the last century into a larger role on the East Coast, where he

became head of the New York Anti-Saloon League and railed as much

against Catholics as he did against demon rum. He was convicted of

forgery in 1924 for altering the league’s financial records. The amount

of money at stake, $24,700, was the equivalent of more than $341,000 in

today’s dollars.

Fifteen

years after Prohibition ended, the Anti-Saloon League of Illinois in

1948 became the Temperance League of Illinois. The organization, which

had been headquartered in Chicago, moved to Springfield in 1954, one

year after Gov. William Stratton banned beer at the state fair. The

group boasted 160 board members that represented 44 religious

denominations and had an annual budget of $120,000, the equivalent of

more than $1 million today. ILLCAAP had $53,000 in revenue in 2012,

according to the most recent financial statements provided to the

Internal Revenue Service, and Churches in Action, its sister agency,

took in $154,200 that same year.

The

organization’s mission has evolved over the years to include fights

against drugs and gambling in addition to pro-temperance stances.

ILLCAAP adopted its present name in 1963, and gambling landed on the

agenda in 1992, when the group’s board voted to fight the expansion of

gambling two years after state lawmakers approved 10 casinos. While

casino companies eyed potential locations, a wave of grassroots

politicking broke out statewide as voters in more than a dozen counties

and municipalities approved referendums demanding a public vote before

casinos could be built in their communities.

In

Sangamon County, Bedell and a handful of allies collected more than

12,000 signatures in less than six weeks during the summer of 1994 to

get the referendum on the fall ballot, setting up camp at summer

festivals, visiting church congregations and going door to door. God did

his part, keeping the weather comfortable – there was appreciable rain

just three days, the temperature rose above 90 only twice and the

average high was a moderate 84 degrees. No one was paid to gather

signatures.

“We had 12 people,” Bedell recalls. “We met every week. It’s a tough thing to do.”

The anti-gambling campaign

turned in signatures three days early, and the 66,380 to 7,123 final

vote was one of the most lopsided margins in county electoral history.

The vote was advisory – the Illinois Constitution strictly limits the

powers of voters to make decisions, and elected representatives in the

Land of Lincoln are notoriously reluctant to give up power. Still, few

politicians welcome being labeled as out of touch with their

constituencies.

“With

90 percent of the people saying they want to have a right to vote,

that’s a pretty strong statement, and it cannot be ignored,” Joe Aiello,

Sangamon County clerk, told the State Journal-Register after results were tabulated.

Politicians paid attention, but only for awhile.

Bedell

and her allies failed in their push for a statewide referendum that

would have required an advisory vote before gambling was expanded

anywhere in the state, with the measure passing the Senate in 1995 but

stalling in the House. Only 49 candidates in 158 races for legislative

seats in 1996 signed pledges promising to support a moratorium on

gambling expansion until voters had a chance to cast ballots in a

statewide advisory referendum. Just 14, including Sen. Bomke, were

incumbents.

In 1999, Bedell lost a fight to maintain a requirement

that riverboats embark on cruises rather than remain permanently

moored, and gambling revenue, with accompanying losses, surged with the

ability of gamblers to enter and leave casinos whenever they pleased.

The biggest blow, she says, came in 2009, when the state legalized video

gambling at bars, restaurants and anyplace else with a liquor license,

essentially establishing mini-casinos in thousands of businesses

throughout the state. Like Poe, Bomke, who retired from the senate last

year, voted for video gambling despite previously taking a stance that

more gambling shouldn’t be allowed without a vote of the people.

Powered

by experience, prayer Bedell had never lobbied a public official before

becoming an ILLCAAP lobbyist in 1994, the same year she became head of

the organization.

“It was hard,” she recalls. “It was what you call on-the-job training. … I knew nothing.”

She

learned quickly. Bedell recalls that her first time testifying before

state lawmakers came at a committee hearing when she and three or four

other opponents of a proposed Springfield casino traveled to the Capitol

to speak their piece. As was customary, the committee chair told

opponents to pick a representative to speak for the entire group. Rep.

Lou Lang, D-Skokie, spoke up, urging the chair to allow everyone to

testify.

“He said,

‘No, I want to know why the rest of you don’t want a casino in

Springfield,’” Bedell recalls. “I was not prepared. I got up and said

something and they put it on television.”

Bedell

says she doesn’t know much about Lang, one of the General Assembly’s

biggest supporters of gambling legislation, but he has always been

courteous. Lang says that some of the information Bedell provides isn’t

detailed or deep, but he doesn’t blame her – that, he says, is the fault

of others who are providing information for talking points.

“She

can’t do everything,” Lang says. “I’m not sure she knows that I admire

her, but I do. … There are a lot of people around here in this building

where I’ve worked for 26 years who end up on the losing side and take it

personally. Anita never does. When Anita comes to the building, she has

a level of gravitas. She has something important to say. She works very

hard to make her points, oftentimes in front of groups of people who

aren’t listening. She doesn’t come with a big political action

committee. She has to do this virtually on her own, and she’s pretty

darn good at it, given all those things.”

No one has to tell Bedell that she’s facing long odds.

“We don’t think that the vote’s going to go our way, but we need to get the message out,” Bedell says. “Silence is consent.”

Bedell

says her passion is powered by personal experience. She recalls

babysitting as an eighth grader for a family with parents who played the

ponies.

“They had

hardly any furniture,” Bedell says. “They had no toys for the kids. At

the end of the week, I didn’t get paid. They’d gambled it all away. … At

the end of the summer, the house was foreclosed on and their car was

taken away.”

Bedell

says she prays before and during legislative hearings when she’s due to

testify, but there is never a spiritual component to her public

comments. Rather, she talks about the social harm and addictive powers

of gambling, alcohol, drugs or whatever else is on the agenda.

“I

don’t think she’s ever used the word ‘smite’ in her life,” says Vickie

Moseley, a former ILLCAAP lobbyist who served one term in the state

House. “She’s just a very down-to-earth Midwestern girl. What you see

when she’s in committee is really Anita.”

A badge of honor Bedell doesn’t have perfect answers for everything. Medical marijuana is one example.

ILLCAAP

opposes medical pot that legislators legalized in 2013, five years

after Lang first introduced a bill. Bedell cites research that shows

negative effects of marijuana on the brain and says the drug kills

motivation in young people. She doesn’t mention the fact that tens of

millions of Americans have used the drug with no ill effects or that pot

smokers have gone on to become presidents or that most any cop would

rather deal with a stoner than a drunk.

“It

(medical marijuana) opens the door for legalization (of recreational

pot) – they’ve said that all along,” she says. “There’s an increase in

use by young people.”

And

what would she say to the cancer patient whose use of marijuana sparks

appetite and eliminates nausea caused by chemotherapy? Or the multiple

sclerosis sufferer whose pain and tremors are eased by a few puffs?

“I don’t know if it works,” Bedell answers.

“It’s not prescribed by a doctor.”

So

far as Bedell is concerned, the sick can start smoking pot when the

U.S. Food and Drug Administration conducts clinical trials, benefits are

proven to outweigh risks and the drug is removed from the list of

substances that the feds say have no legitimate medical use. It’s

typical of the strong stances Bedell takes, and it’s her commitment that

wins admiration.

“She’s

one of those people who don’t rely on the kindness of strangers,” says

Moseley, who now works in the securities division of the secretary of

state’s office. “She feels very strongly about this issue, not just the

gambling issue, but the addiction issue and how it impacts lives. This

is her niche. This is where she wants to make her mark on the world.”

Bedell

says she considers Moseley a mentor who taught her the ropes at the

Capitol. Moseley says that’s too much credit. While Grey, the reverend

who moved from Illinois to combat gambling on the national level, was

focused on public relations and the media, Moseley says that she concentrated on armtwisting legislative staff while working for ILLCAAP. Bedell, she says, did both.

“Anita

was bouncing back and forth between the two of us,” Moseley recalls.

“She would come and testify before committees and then be at the press

conference the next day. She was doing all of it, plus running the

(ILLCAAP) office.”

Moseley recalls Bedell enlisting nuns to write letters to lawmakers.

“When you get a letter with O.P. below the name, you take a moment to think about it,” Moseley says.

While

the common wisdom holds that Bedell is tilting at windmills, Moseley

points out that there are no casinos or statesanctioned video gambling

machines in Chicago. She recalls driving to the West Coast in the late

1990s and seeing widespread legal gambling in one state after the next.

“We didn’t get it until now,” Moseley says.

“If you’re looking to point to something that she did, we could have had it a lot sooner.”

Church lady. Moseley has heard the label.

It should not, she says, be considered an insult.

“I

would call it a badge of honor,” she says. “If that’s the voice you

would pin on Anita, that’s a good voice. I’ve been called a heckuva lot

worse.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].