Getting it right

Freeing the wrongly convicted with the Illinois Innocence Project

CRIME | Patrick Yeagle

Brian Banks had the world at his feet.

A promising high school football star with serious NFL prospects, Banks got his first college recruiting letter as a sophomore. Before he even started his senior year of high school, he was recruited to play football at a prestigious university, where he wanted to study journalism.

But Banks’ favorable trajectory was violently thrown off course in the summer of 2002 when he was accused of rape. He would spend five years behind bars and another five years wearing an electronic monitoring anklet before new evidence would clear his name.

Banks is one of more than 1,340 people across the nation who were freed from prison between 1989 and 2014 after being imprisoned for crimes they didn’t commit. Now Banks is a crusader for the group that helped free him, and he is coming to Springfield next month to spread his message of hope for the wrongly convicted.

Brian Banks grew up in Long Beach, Calif., just south of Los Angeles. He stood out on the football field at Long Beach Polytechnic High School, where he played linebacker because of his size and agility. Banks’ athletic prowess got him scouted to play football for the powerhouse University of Southern California.

In the summer of 2002, a couple of weeks before his 17th birthday, a young woman at his school claimed Banks dragged her into a stairwell and raped her. Although the only evidence against Banks was his accuser’s words, prosecutors offered Banks a deal: plead guilty in exchange for a sevenyear prison sentence and a lifetime of registering as a sex offender. The alternative was fighting the charge and risking a 41-year prison sentence.

“My attorney told me ‘When you walk into that courtroom, you will be automatically assumed guilty because you are a big, black teenager, and you will more than likely have an all-white jury,’ ” Banks said.

He had 10 minutes to make his decision and wasn’t allowed to talk to his mother about it. He chose to take the plea deal and served five years and two months in prison. Meanwhile, Banks’ accuser sued the Long Beach school district, saying the school wasn’t safe. Her family won a $1.5 million settlement.

Banks was released Aug. 29, 2007, and had to wear an electronic monitoring anklet as a term of his parole. He couldn’t find a job because of his criminal record, and California’s laws regarding sex offenders meant he couldn’t live within 2,000 feet of a school or park, so he lived at home with his mother. But Banks’ nightmare was almost over.

After Banks was released, he received a Facebook friend request from his accuser. She also sent Banks a message saying she was more mature now and wanted to “let bygones be bygones.” Banks immediately saw an opportunity to clear his name.

He convinced his accuser to meet him at the office of a private investigator, who had wired his office with hidden cameras and microphones.

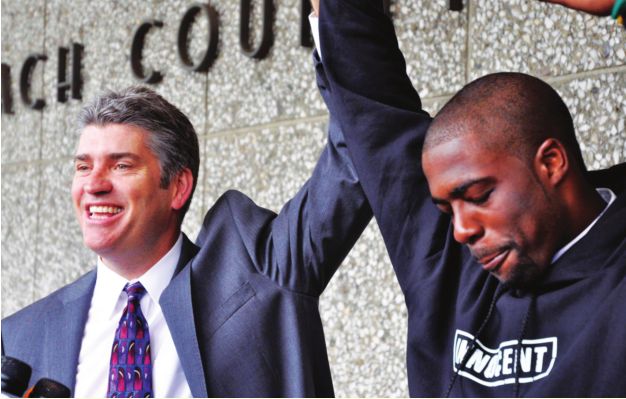

Banks’ accuser was recorded admitting that Banks didn’t rape her, but

she was reluctant to do anything that might mean her family would have

to pay back the $1.5 million settlement from the school district.

Banks

took the recording to the California Innocence Project, which helped

him gain a new hearing in front of a judge. The evidence was enough to

clear Banks of the made-up crime, and he walked out of the Long Beach

courthouse smiling on May 24, 2012.

“I

was thinking ‘Finally, the truth is out and I’m free,’” Banks recalls.

“Here I am now with a window of opportunity to do something with my life

that I wasn’t able to do before. There were a bunch of emotions, but it

was definitely bittersweet because of the 10 years I lost.”

After

Banks’ conviction was overturned, the Long Beach school district sued

the accuser and her family to reclaim the earlier settlement. A Facebook

page dedicated to advocating for the prosecution of the accuser has

nearly 1,300 followers, but authorities have been reluctant to pursue

the case.

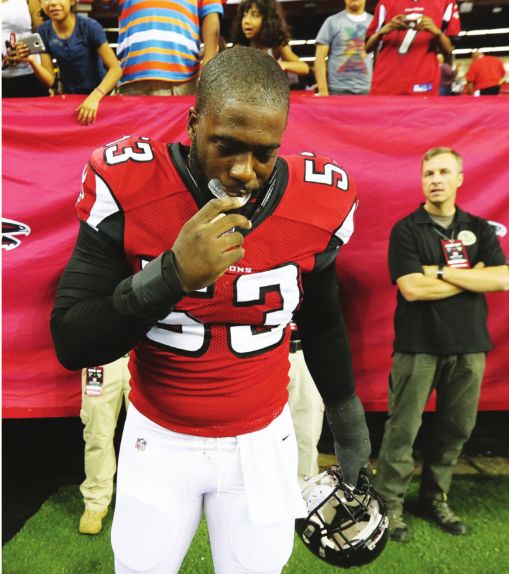

Banks

finally got to play in the NFL after being drafted by the Atlanta

Falcons in April 2013, and he made his debut in August of that year,

making two tackles. However, the team cut him later that month while

downsizing from 75 players to 53. Banks is currently an unsigned free

agent, but he is focusing on more meaningful pursuits now. He’s

attending college to become a life coach, and he’s currently shooting a

documentary. He also recently signed a deal to make a movie about his

life.

“We may not be

in control of the things that are happening in our lives, but we are in

control of how we carry ourselves through a situation, and how we allow

those situations to affect us,” Banks said. “While you’re dealing with

things that are out of your control, just work on what you do have

control over: bettering yourself as a person.”

Justin

Brooks, the director and co-founder of the California Innocence

Project, helped Banks clear his name. Besides his work with the

California Innocence Project, Brooks created RedInocente, an

organization dedicated to establishing innocence projects across Latin

America. Brooks will visit Springfield with Banks to speak at the

Illinois Innocence Project’s annual Defenders of the Innocent banquet on

May 3.

Fighting to get it right

The

Illinois Innocence Project is one of about 60 groups around the U.S.

dedicated to reversing wrongful convictions. Started in 2001 at the

University of Illinois Springfield as the Downstate Innocence Project,

the Illinois Innocence Project has expanded to cover the entire state

with the help of Illinois’ three largest public universities: the

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Northern Illinois University

in DeKalb and Southern Illinois University in Carbondale. So far, IIP

has secured the release of six people, with several other cases in

progress.

Larry

Golden, founding director of IIP, says the organization is constantly

inundated with requests to take cases, so a set of rules helps determine

which cases get taken. IIP accepts only cases in which the accused is

likely to be actually innocent and has four years or more left on his or

her prison sentence. The crime in question must be a felony, and there

must be a significant chance of finding new evidence to overturn the

conviction.

The

Illinois Innocence Project is unique among its fellow projects because

it uses undergraduate students to review the requests to find which

cases have potential. That helps the project’s staff attorneys focus on

current cases, and it gives the students handson experience with legal

work. Many of the students plan to attend law school after graduation

from UIS. The students pore over evidence, interviews and court

documents, then write up a synopsis of each case, which gets reviewed by

a committee of lawyers, staff members and other students.

Once

a case is accepted, it goes to students at one of the other

universities’ law schools, who work with the IIP staff attorneys at UIS

to look for new evidence and navigate the legal process. IIP only has three

full-time attorneys and one part-time attorney who split their time

among about 10 students at each university.

Golden

says innocence projects are primarily concerned with “getting it right”

– putting the right people behind bars and keeping the wrong people out

of prison. He cites research showing that one out of every 10 people on

death row is innocent. While Illinois no longer has a death penalty,

the statistics on wrongful convictions paint a frightening picture of a

flawed justice system.

“If

one out of every 10 planes crashed or one out of every 10 surgeries

went wrong, wouldn’t we as a society want to do something about it?”

Golden said. “It’s time for us to think about what we should do to make

our system better. Ultimately, we want the same thing as prosecutors and

judges: we want to see the system work the way it’s intended to work.”

Recent victories

In

the 12 months between spring 2012 and spring 2013, IIP helped get three

wrongfully convicted people out of prison. The 2012 exoneration of

Jonathan Grayson of Aurora was especially noteworthy because it involved

the cooperation of police and prosecutors.

Previously

known as Jonathan Moore, Grayson was convicted of murder and two counts

of attempted murder in 2002, which resulted in a 60-year prison

sentence. Grayson’s case originated in August 2000 thanks to a pair of

shootings in Aurora. One of the victims survived and chose Grayson, then

age 20, out of a police lineup. Although the victim’s testimony in

court conflicted with that of another eyewitness, Grayson was found

guilty.

In January

2011, while Grayson was still serving his sentence, another shooting led

police to new suspects who possessed the gun used in one of the

previous shootings. A new eyewitness also came forward, and the Aurora

police and the Kane County state’s attorney reopened their

investigation. The investigation turned up new evidence and testimony

that discredited the original eyewitnesses, and Grayson’s conviction was

vacated.

Also in

2012, the Illinois Innocence Project saw the release of Anthony Murray

of Chicago, though that release was bittersweet. Murray was accused and

convicted of a June 1998 murder in Centralia and given a 45-year prison

sentence, despite inconsistent testimony from the key witness. The

evidence in Murray’s case has been contaminated by years of sitting

unsorted and commingled in shopping bags, so the chances of finding a

new means of proving his innocence were slim. After fighting to get a

new trial for 14 years, Murray, in consultation with the Illinois

Innocence Project, decided to take what’s known as an “Alford Plea,” in

which the defendant must admit to one criminal charge in order to avoid a

more serious charge. By pleading guilty to a second-degree murder

charge, Murray got credit for the 14 years he spent in prison and was

released on Oct. 31, 2012. He maintains he is innocent.

The

Illinois Innocence Project secured the release of a third person in

2013, this time through a clemency petition approved by Gov. Pat Quinn.

Peggy Jo Jackson, who now goes by her maiden name, Harshbarger, spent 26

years in prison for the murder of her former husband, William Jackson. The pair

lived in Mt. Vernon, and William was allegedly abusive to Peggy Jo and

their children. After William’s murder, Peggy Jo’s brother, Richard

Harshbarger, told police he shot William during a scuffle.

Along

with Richard, Peggy Jo was tried and convicted of William’s murder

because prosecutors said she asked Richard to kill her husband. The

prosecutor’s theory hinged on Peggy Jo not being upset enough about her

husband’s death, but medical records show Peggy Jo had been placed on

strong drugs to calm her trauma and treat her intense depression. The

drugs are credited with dulling Peggy Jo’s reaction to the murder. Peggy

Jo was also believed to have lied to police about not knowing William

was dead because Richard threatened to kill her if she spoke about it.

Richard died in prison in 2006.

The

Illinois Innocence Project helped Peggy Jo assemble a clemency

petition, gathering letters of recommendation from family, therapists,

prison officials and even her original public defender, who said the

case continues to haunt him because he was not experienced enough to

handle the case by himself. Gov. Pat Quinn approved Peggy Jo’s petition

in March 2013, freeing her from prison after 26 years.

A possible future exoneration

IIP

staff attorney Lauren Kaeseberg is working on a case that she hopes

will see a major advancement in the coming months. Details that would

identify the case have been withheld to avoid endangering an agreement

between IIP and the state’s attorney prosecuting the case.

In

the summer of 1993, an Illinois woman was found dead in her home,

stabbed 30 times in the bathroom. The police found the murder weapon,

along with several bathroom items which had blood on them. At the time,

DNA testing was still rudimentary, so blood samples and other samples

taken from under the victim’s fingernails were never tested.

The

police initially had no leads in the case, so they looked at the

victim’s phone records and found calls from a relative’s workplace to

the victim’s home around the time of the murder. The relative, a man who

was related by marriage to the victim, was a Mexican immigrant who,

along with his wife and children, spoke very little English at the time.

He quickly became the only suspect in the case.

Kaeseberg

says the detective who investigated the case was the only

Spanishspeaking officer in the area at the time. The detective

interrogated the victim’s relative, telling him that the police had

evidence linking him to the murder weapon and that his family would be

arrested if he didn’t confess. Kaeseberg says the detective also beat

the relative during the interrogation. In order to protect his family,

the relative agreed to sign a confession – written in English – on the

assumption that he could later take it back when he was no longer in the

detective’s presence.

The

detective served as an interpreter between the relative and the state’s

attorney who was prosecuting the case at the time. That means the

suspect’s words were filtered through the detective before they reached

the state’s attorney. Kaeseberg says the detective in the case is

suspected of producing false confessions and evidence in other cases.

The

relative was convicted and sentenced to life in prison, but Kaeseberg

and IIP believe he was innocent. The current state’s attorney has agreed

to allow DNA testing of the samples taken from the crime scene, which

could rule out the relative as a suspect.

Kaeseberg

says suspects in criminal cases are rarely seen sympathetically by the

public, so revealing problems – like the lack of an impartial

interpreter and untested DNA evidence – helps bring reforms.

“I’m

really passionate about this work,” Kaeseberg said. “Part of the reason

I find it so important is not only are we working on individual cases

of clients, working to clear their names, but if you look at the current

state of the criminal justice system, really the only thing that’s

causing systemic change is exonerations.

We apply what we learn from

these cases to the system, and it helps enable reform and legislative

change where it’s incredibly necessary. No one can deny the horrors of

an innocent person being convicted of a crime they didn’t commit, so the

visceral reaction to that problem actually forces change to happen.”

Addressing systemic problems

In

order to prevent future wrongful convictions, the Illinois Innocence

Project also works with state lawmakers on legislation to correct

problems in the criminal justice system. IIP previously pushed

successfully for videotaping of interrogations, and the group currently

supports a bill that would allow criminal defendants who plead guilty to

obtain DNA testing of evidence in their case.

John

Hanlon, executive director and legal director for IIP, says most people

who plead guilty to crimes do so because they are guilty, but in cases

like the one Kaeseberg is handling, the suspect pleaded guilty out of

fear. Hanlon says the legislation would give people like Kaeseberg’s

client a chance to prove their innocence even if they already gave a

false confession.

The

Illinois Innocence Project opposes a separate bill that would codify a

controversial condition known as “shaken baby syndrome” into state law.

Shaken baby syndrome is often cited by doctors and prosecutors to

explain infant deaths when the child has a “triad” of symptoms: brain

bleeding, brain swelling and retinal bleeding. In those cases, the last

person to care for the child is typically charged with murder on the

theory that they shook or even hit the baby. However, many of the cases

labeled as shaken baby syndrome involve other medical conditions that

predated the triad of symptoms, and new research shows that old

assumptions about shaking infants may be misguided.

IIP

is working on at least one case involving shaken baby syndrome. Pamela

Jacobazzi is currently in prison at Logan Correctional Center in Lincoln

for the 1994 death of 10-month-old Matthew Czapski of Bartlett, Ill.

The Illinois Innocence Project believes Jacobazzi is innocent because

Matthew Czapski had pre-existing medical problems that may explain his

death.

An uphill battle

Larry

Golden, IIP’s founding director, says obtaining an exoneration is an

arduous task, from unearthing new evidence to simply getting a judge to

grant a rehearing.

“Every

step, from allocating resources for help to viewing their claim of

innocence in a favorable light, is actually resisted,” Golden says. “The

system is just set up that way, so it’s a struggle. What that means is

that the simplest of motions is likely to be denied. The work that goes

into a given case is going to span years.”

That

means the Illinois Innocence Project must rely heavily on grants and

long-term community support; the organization receives no money from

UIS. Golden sees a contributions to IIP as an investment that saves

money by reversing wrongful convictions. IIP estimates that taxpayers

paid more than $1.5 million to keep Jonathan Grayson, Peggy Jo

Harshbarger and Anthony Murray behind bars until they were freed.

Statewide, the Chicagobased Better Government Association says it cost

taxpayers more than $214 million to keep 85 wrongfully convicted people

behind bars for a collective 900 years of prison time.

“We

become very intertwined with these people,” Golden said. “The work we

do ultimately involves personal investment that creates a bond between

the students, the staff and our clients. It’s a very unusual situation.

They are not just clients; they become almost part of our family. There

is nothing more gratifying than walking a person out of prison who you

know is innocent and giving them a piece of their life chances back.

It’s a feeling that cannot be described in words.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].

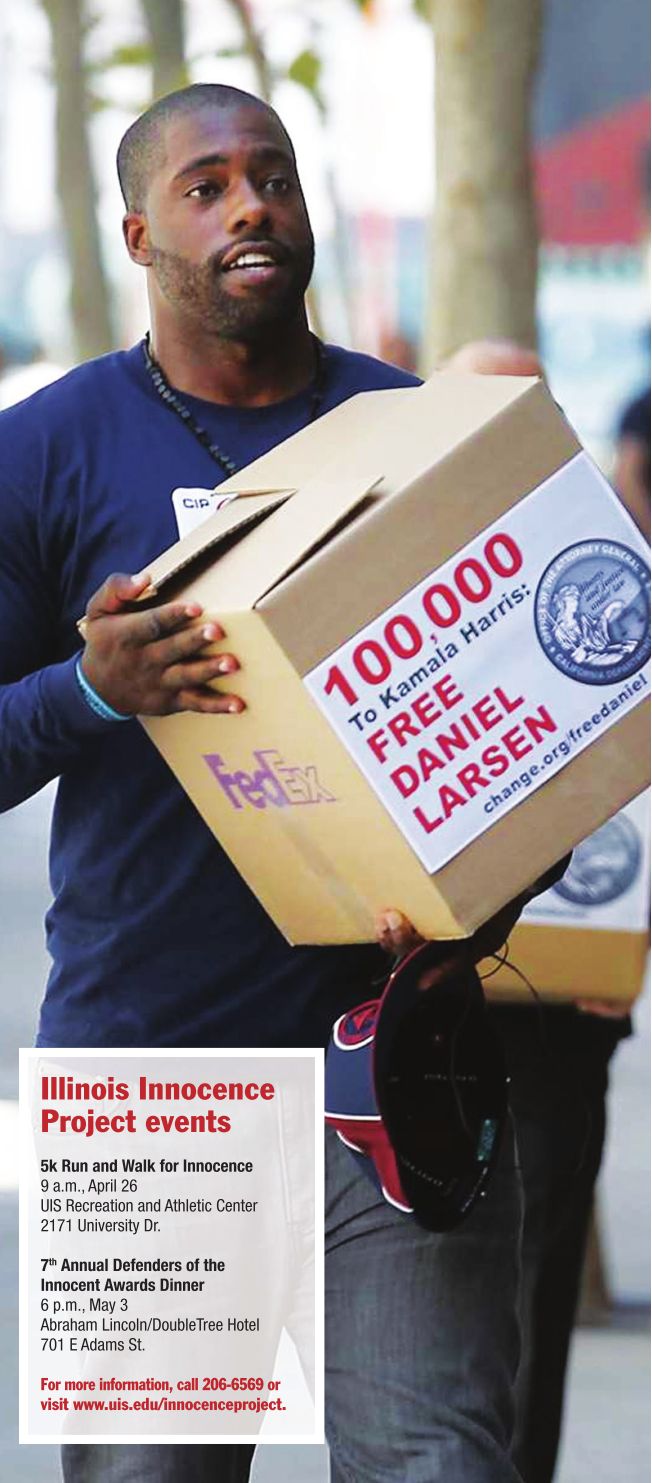

Brian Banks spent five years in prison for a rape that never occurred, but he was freed with help from the California Innocence Project. Banks is shown here carrying petitions calling for the release of another prisoner in California whom some believe to be innocent. PHOTO BY BRIAN VAN DER BRUG/MCT