A beacon for ex-cons

Tower of Refuge gets parolees on the right path

CRIME | Patrick Yeagle

Before he was even 12, Lorenzo Louden had shot a man and slept with two prostitutes. Growing up so early, it’s no wonder he preferred gang life to school and eventually wound up in prison.

Now 57, Louden runs the Springfieldbased nonprofit Tower of Refuge with his wife, Bevey. Using his life experience and her administrative skills, the Loudens help prison inmates and recently released ex-convicts acclimate to the “normal” world that is foreign to many of them. The former criminals are guided to a lifestyle of responsibility, self-discipline and selfexamination that many of them have never known, but which is necessary to keep them from returning to prison.

Tower of Refuge boasts a 92 percent success rate, meaning almost all of the former inmates who go through its program stay out of prison. Contrast that with the 52 percent of inmates statewide who return to prison within three years, either for committing new crimes or violating their parole. Tower of Refuge teaches inmates how to get a job, how to live within society’s expectations, and how to survive without reverting to their old, destructive ways.

Born in Little Rock, Ark., and raised on Chicago’s west side during the ’60s and ’70s, Lorenzo Louden spent his early years learning how to survive on the streets. He bounced between living with his mother, who worked as a prostitute, and various aunts and uncles. Louden never knew his father.

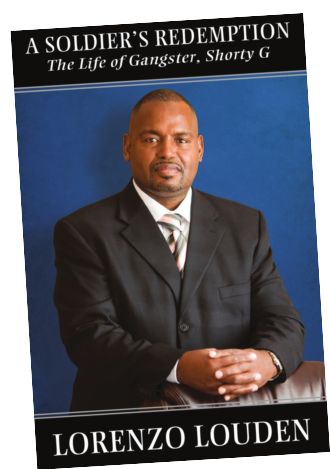

In his memoir, published in 2013 and titled A Soldier’s Redemption, Louden recalls trying to shoot one uncle who attacked him in a drunken stupor, learning about sex from a prostitute, and failing seventh grade after beating a teacher with a baseball bat – all by age 12.

While living with family in the rough K-Town neighborhood of Chicago, Louden got involved with the High Supreme Gangsters, which later merged with another gang to become the infamous Gangster Disciples.

“I was like a second-class citizen in everybody else’s household, so I found my camaraderie with guys on the street instead,” Louden said. “We looked out for each other. They became more my close-knit family than my real family. A typical day with us was just hanging out in the streets, cutting class from school, and figuring out how we could make some money…bullying people walking down the street, fighting the other gangs, that kind of stuff.”

Looking back, Louden says his bad behavior was the result of not feeling loved by his mother, who had too many problems of her own to be an effective parent.

“I loved my mother so much,” he said. “I think that with her not showing that interest in me and me seeing how everyone else had a family connection, I acted out from that.”

Louden frequently got in trouble with the law and had to lay low or even get out of town to avoid arrest. After one particularly brazen criminal act, in which he shot a man on the street in broad daylight over a few bottles of booze and $30, Louden got arrested and was bailed out by one of his mentors, whose name was “Uncle” Ray. He knew he owed Ray big, so Louden went along with a scheme Ray concocted for a big payday.

The plan was to kill an acquaintance named Phil and then split the $1 million life insurance policy with Phil’s widow. One summer night in 1976, Louden shot Phil three times and killed him. He went into hiding again, but a friend ratted him out.

Louden was arrested in 1977 and convicted of Phil’s murder.

While in prison serving an 18-year sentence for conspiracy to commit

murder and a 50- to 60-year sentence for murder under Illinois’ former

indeterminate sentencing system, Louden rose through the ranks of the

Gangster Disciples to become a gang chief. He also continued to cause

trouble while behind bars, which prompted the Department of Corrections

to shuffle him from prison to prison. Louden says in those days the

department would move inmates around constantly on what was known as

“the circuit” to keep them from becoming too comfortable or gaining too

much power in a particular prison.

“It

was like I switched off my humanity,” Louden recalls. “I had to live

this life of not caring about others because it wasn’t guaranteed that

you would wake up the next day.”

Louden’s

nickname, “Shorty G,” was given to him by a fellow inmate who observed

that Louden never backed down from a fight, even when he was outmatched.

“He said I had a big heart, but I was short on wits,” Louden said with a laugh.

Several

years and several parole rejections into his sentence, Louden became

resigned to serving his time. In 1991, he attended a church service in

prison led by a former cellmate who had become a missionary after

leaving prison. Louden says he attended just to support his friend, but

in the midst of the service, Louden began sobbing. He says all of the

emotions and regrets he had suppressed during his criminal acts came to

the surface. Louden became a Christian and was later baptized.

When

the Illinois Prisoner Review Board compared his post-conversion record

with his previous violent track record, they voted to release him.

Louden got out of prison on March 3, 1994, 20 years ago this month. He

had served more than 17 years behind bars, and he would serve another 10

years on parole, which he completed in 2004.

As

a term of his parole, Louden wasn’t allowed to go back to Chicago, so

he settled in southern Illinois and then moved to Springfield in 2002.

It was here he met Bevey Wilson, his future wife. Louden says he was

completely honest with Bevey about his past, and the pair got married in

August 2002.

Gaining

respect post-prison as a successful businessman with his own basement

waterproofing business, Louden soon began to get requests from

ministers, schools and prison wardens to tell his story. That led Bevey

to ask Louden how he was going to “pay forward” the change that God had

made in his life.

“When

I came into his life, he was the Lorenzo we all know him to be now, but

as he talked about his story and the different things he encountered, I

could not relate the two,” Bevey said. “I thought, ‘How do you live

that life and then morph into something else, like completely black and

white?’ I knew that there was a powerful testimony in his life, and his

story related to a larger problem that we have in our country. I thought

if he could make such a metamorphosis – it’s a true

caterpillarbutterfly story – why couldn’t somebody else learn from

that?” They started Tower of Refuge as a nonprofit in 2005, with Louden

visiting prisons to speak to current inmates about how he changed his

life and what they need to do to change theirs.

“Our

true passion in the reentry is to be in the prisons,” Bevey said. “It

started with the goal to reach people where they are. It’s like a

neutral zone, because they’re not in their criminal lifestyle, but they

haven’t gotten their freedom, either. That’s a very captive time period

for a person to truly make some life decisions, and we can reach them in

their moment to help catapult their decision process.”

“It’s like a bright light, shining over the

ocean and guiding the ships into shore,” he said. “We want to guide

people into a haven of hope where they can become better citizens.”

In 2007, they expanded their focus to include recent parolees.

“The

more we got involved in the prisons, the more we saw a need to help

people once they left prison,” Bevey said. “Who is out there guiding

them after we’ve given them a lot of motivation and inspiration, and

they’ve made some tangible decisions but didn’t get to practice them

until they left?” Lorenzo Louden says the organization’s name refers to

being a beacon of hope.

“It’s like a bright

light, shining over the ocean and guiding the ships into shore,” he

said. “We want to guide people into a haven of hope where they can

become better citizens.”

Contracting

with the Illinois Department of Corrections, Tower of Refuge fills a

gap in services for prisoners entering the free world. Without groups

like Tower of Refuge, inmates and recent parolees go from violent

prisons, where they live in constant survival mode, to the streets of

whatever city they’re released in. That survival mindset is tough to

shake, Louden says, and more than half of parolees statewide end up back

in prison. Homelessness, substance abuse and lack of employment are

also common among parolees.

To

help inmates and parolees transition to life outside the prison walls,

Tower of Refuge’s “Finish Line” program involves meeting with inmates

two years before their projected release dates. The inmates take a

cognitive behavior course that teaches them to think through their

problems instead of reacting destructively. Inmates are encouraged to

reunite with family and let go of old wounds while also learning résumé

writing, interview skills, job skills and business etiquette.

When

inmates are released and become parolees, Tower of Refuge offers help

with finding housing, paying bills, developing a budget, getting a state

identification card and other common tasks many people take for

granted. The parolees may also receive counseling, mentorship, job

referrals and health education on issues like HIV and AIDS.

Louden

and his staff work with Safelink, the federally supported phone service

for low-income families and individuals, to make sure parolees have a

basic cell phone plan. Additionally, the parolees are offered a chance

to obtain health insurance through the federal health care reforms of

2010.

Once each month,

Tower of Refuge also hosts a meeting of the Community Support Advisory

Council. Known as CSAC, the group gathers employers, nonprofits, state

agencies, clergy and others to solve problems, share resources and

discuss opportunities for parolees. The Illinois Department of

Corrections has six CSAC groups in Illinois, situated in areas of the

state where the most parolees return after prison. At the March CSAC

meeting in Springfield, held the day after Louden’s 20 th anniversary of

getting out of prison, attendees talked about job opportunities,

services for single mothers, and getting parolees enrolled for health

insurance. The connections made at the CSAC meetings allow parolees to

get help from both charities and government which the parolees may

otherwise never have known existed.

A

Soldier’s Redemption - The Life of Gangster, Shorty G, by Lorenzo

Louden, paperback, 208 pages, Dog Ear Publishing, published April 2013.

Available through Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

Amazon link: http://amzn.com/1457519445

Barnes & Noble link: http://tinyurl.com/l86dlqt

Louden says Tower of Refuge

takes on 60 to 70 new clients each month on average, which works out to

between 720 and 840 clients annually. Considering Tower of Refuge’s

success rate of 92 percent, that equates to roughly 700 people each year

avoiding a return to prison.

Tony

Robertson, a receptionist at Tower of Refuge, says he enjoys his job

because he likes helping people. He is currently attending Benedictine

University in Springfield, where he plans to graduate in 2015 with a

degree in social work. He’s one of only six staff members at Tower of

Refuge, not including the Loudens themselves.

Tony

Robertson, a receptionist at Tower of Refuge, says he enjoys his job

because he likes helping people. He is currently attending Benedictine

University in Springfield, where he plans to graduate in 2015 with a

degree in social work. He’s one of only six staff members at Tower of

Refuge, not including the Loudens themselves.

“We can help people who can’t really help themselves, and we can help them change their lives,” Robertson said.

Lawrence

Poindexter is a reentry specialist with Tower of Refuge, and he’s also

one of the organization’s success stories. Before becoming a client with

Tower of Refuge, Poindexter had been living in Chicago without a job or

a place to stay. He says he came to Springfield to visit his father,

who told him about Tower of Refuge. Although Poindexter had already

completed his parole before joining the program, he says he still had a

lot to learn.

At the time, Tower of Refuge needed a tech-savvy employee to manage the organization’s databases

and computers. Poindexter had already learned those skills in school, so

he started working for Tower of Refuge in 2011. He says being able to

help people who were in the same situation he had been in helped him get

his life in order.

“Helping

those people navigate through the process (of reentering society) was

great,” he said. “It made me view myself a little bit.”

Poindexter

says Tower of Refuge taught him to do things like manage his money –

small skills that make a big difference in being self-sufficient and

stable.

“They helped me make better decisions,” he said.

Poindexter says Tower of Refuge works because the parolees want to be there.

“The

key to the program is the person,” he said. “That unlocks all the

doors. That person has to actually be ready to change their life. We’re

talking about habits that are part of their environment since birth or

even prior to that because of their lineage. It’s them wanting something

different, and they start seeing they have to do something different.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].