A fresh effort to care for Lincoln’s river

CONSERVATION | Jeanne Townsend Handy

Rivers have dictated the history of life itself, drawing to it animals, with humans in their wake. There are celebrated, legendary and notorious rivers – rivers that rage and those that range across countries and continents.

The Sangamon River, casually winding 246 miles through the unchallenging landscape of central Illinois, seems a beautiful but shallow pretender to the name “river.” Yet between its banks are eras of consequence – stories of native peoples and a president, and a legacy reliant upon recognition of its past and continued importance.

A Great Blue Heron acts as an impromptu trail guide, leading our canoe along a small segment of the 65-mile stretch of the lower Sangamon River known as the Lincoln Heritage Water Trail. As we draw near and lift a camera, the heron rises and disappears beyond the next turn, at once shunning us and beckoning us onward – elusive – like the glimpses of history found along the Sangamon.

“There is a really cool limestone formation up ahead that was part of an ancient seabed when it was laid down 200 million years ago,” says Scott Hewitt, president of an organization called the Lincoln Heritage Water Trail Association, a group promoting awareness, accessibility and habitat protection for a “fantastic natural resource for canoeists, kayakers and photographers.” On this day, Hewitt acts as our official guide, historian and unflagging paddler.

The steep and scoured banks flanking the river reveal layer upon layer of history, from seabed limestone to coal to landscape anomalies sheltered behind trees high upon the bluffs, which Hewitt believes to be remnants of former Native American occupation – possible burial mounds? He tells of the river’s proclivity for offering up material evidence of ancient times and ancient peoples. Nearby are traces of former wagon trails, which themselves may have followed the remnants of bison trails.

Communities have followed communities. And one day a future president arrived.

The Lincoln Heritage Water Trail spans two historic sites – the Lincoln Homestead State Park near Decatur and the New Salem State Historic Site near Petersburg. These sites bracket an Abraham Lincoln tale, replete with quick wit and strong will, that began in 1831. It starts with a canoe trip by a 22-year-old Lincoln upon a flooding Sangamon River from his family’s homestead site near Decatur to the Springfield area. At Sangamo Town, seven miles northwest of Springfield, he built an 80-foot flatboat and set off for New Orleans but ran aground at the mill dam below the New Salem bluff. Undaunted, he saved it from sinking (with an auger commandeered from the village cooper shop) before continuing his journey.

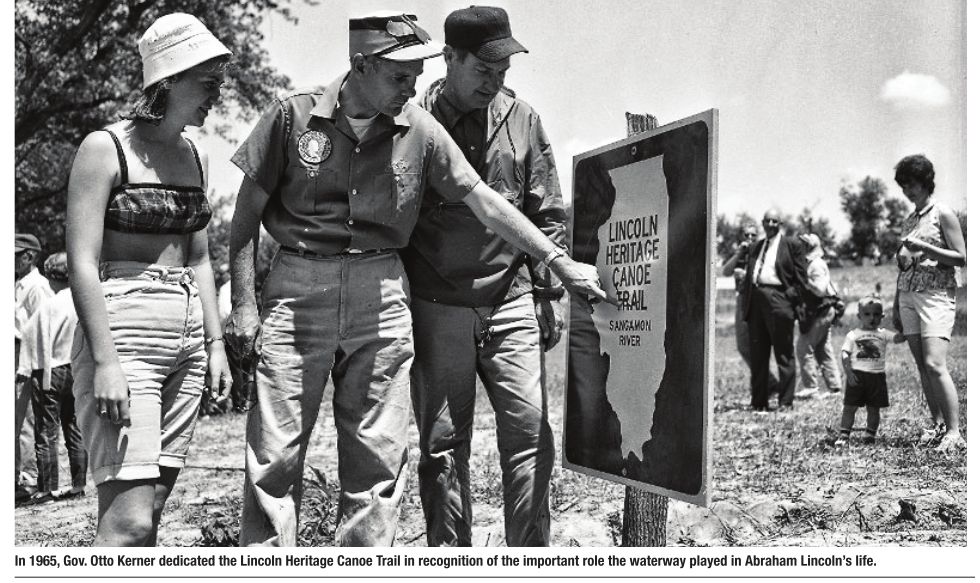

These events helped mold the person Lincoln would become, making this stretch of river worthy of special recognition, which it received in 1965 when Gov. Otto Kerner dedicated what was then called the Lincoln Heritage Canoe Trail. More than 70 canoes took part in a three-day excursion. Photos from the event feature dignitaries and women paddlers with cat-eye sunglasses and “Boy Scout Indian dancers” performing around a bonfire at an overnight stop. But despite this “big sendoff” in 1965, the vision for improving access, site interpretation, navigation and habitat protection along the trail has since languished.

In a revived effort to draw attention to a largely unknown and untraveled length of river and with a nod toward the excitement and events that transpired during the dedication in 1965, the Lincoln Heritage Water Trail Association launched its inaugural canoe and kayak race – Abe’s Race – on Oct. 5. . The event was intended as an attention-grabber for the association, a sidebar to their efforts to protect the river’s cultural history from abuse and neglect and to guard the natural history

from pollution and invasive species. To care about a place, people must

experience it, and despite the threat of storms, 60 paddlers turned out

for the event.

In

contrast to the race, our canoe sojourn was solitary and serene. With

trees sheltering us from the sight of the 21 st century, with the only

sound being that of bird song accompanied by the dip of the paddle, this

passage through the landscape does indeed seem unchanged from the time

of Lincoln and from the time of poet Edgar Lee Masters, who wrote of a

New Salem bluff in his 1942 book, The Sangamon: “Coming from the

sunlit prairie, the bluff is reached that overlooks the Sangamon River

which winds from the southeast, and then bends west striking the bluff.

The bluff is of some height and gives a view of the hills to the east,

and looks down upon the forestry along the river. It is one of the most

beautiful prospects in Illinois, or anywhere in America.”

My

eyes travel from sky to treetops to river, only to see sky again

mirrored upon its surface. I wonder at the scoured banks, the exposed

roots, the toppled trees that have come to rest within the water. Could

the river possibly have swelled so high? Hewitt confirms that it has

been known to rise “easily 20 feet over our heads.” A turtle silently

slips off a protruding snag and beneath the surface upon our approach.

We admire a beaver lodge that surely should be called a mansion, and the

heron allows us to get a bit closer – before once again beckoning us

onward.

“Eagle!”

exclaims Hewitt in hushed excitement. He thinks he has spotted one of

two juvenile eagles he has come to know and expect as a regular paddler

on this section of the Sangamon. But like the heron, it vanishes before

we can draw near. We scan the treetops in vain, and Hewitt begins

questioning his sighting until we come upon a flathead catfish lying

near the shore with a fresh gash in its flank. We recognize that we have

interrupted an eagle’s meal and decide to slip our canoe in amongst the

branches of a nearby downed tree, thinking it a good blind to await the

eagle’s return.

The birds we have spotted and almost spotted

and those we can only hear are a reminder that while rivers may no

longer be dictating human destinies – no longer pulling us together or

guiding us to new destinations – they remain crucial corridors for

wildlife. Lincoln’s name is attached to this trail, yes, but what are

the names of the other species that have known this river for centuries?

They are many. An Illinois Department of Natural Resources 2003

inventory of the Lower Sangamon River valley reveals that “diverse

habitats and largely rural landscape provide homes or rest areas for

nearly every species of bird found in Illinois.” And by “nearly every

species” they mean all but one of 300 bird species found in Illinois, 30

of which are listed by the state as threatened or endangered. For other

species the numbers are nearly as high: Eighty percent of the state’s

mammals can be found in this valley as well as almost half its plants

and reptiles.

This

report also stresses that natural resource protection must expand

beyond single species and relatively small tracts of public land.

Ecosystems do not begin and end within the boundaries drawn up on maps

or plats, and in a state like Illinois where 90 percent of the land area

is privately owned, stewardship is possible only through partnerships

between public and private interests.

Likewise,

if the Lincoln Heritage Water Trail is to become more easily explored

and enjoyed, more strenuously protected from such threats as pollution,

siltation and habitat fragmentation, public and private groups need to

come together in common cause to provide organized maintenance and

management. Many of the existing water trails in Illinois are located

within forest preserves and park districts but, as Hewitt notes, the

Lincoln Heritage Water Trail is located “in the middle of farm country.”

Further

complicating the situation is Illinois water law, which states that a

stream is considered “navigable” only if it is capable of conducting

commerce. And if it is nonnavigable, a stream is “not among the public

waters of the state.” Of the 65 dedicated miles of the Lincoln Heritage

Water Trail, roughly 32 miles in Macon and eastern Sangamon County are

considered non-navigable by Illinois water law. In other words, this

segment of the trail is, in fact, private property.

It

will take more than one group to tackle the obstacles, and The Lincoln

Heritage Water Trail Association website lists nearly 30 other groups as

“friends” who are assisting in their efforts to promote and protect the

trail. Additionally, the Illinois Department of Natural Resources has

launched a planning effort to ensure a safe and easy-to-navigate trail

system. The plan will address amenities, maps, signs and mile markers

with development guidelines formulated by stakeholders and the public in

all three counties along the trail’s path.

Louis

Yockey of IDNR notes that the planning effort goes even further. “The

plan will also look at existing Illinois water law, and determine the

effects the non-navigable status of a section of the trail has on

recreational use and land rights,” he states. Yockey adds that Gov. Pat

Quinn recently signed into law legislation that extends liability

protections for landowners

who allow the public to freely access their property for conservation

and recreational activities like canoeing, which will take effect Jan.

1, 2014. If the goals devised through the planning effort are achieved,

the state of Illinois may seek National Water Trail designation by the

National Park Service.

After

determining we are not deceiving the eagle within our makeshift blind,

we move on. As we near the end of our journey, Hewitt mentions that

while the Lincoln connection to the trail should increase interest in a

waterway already abounding with natural history, some local people are

tired of hearing about Lincoln’s exploits. Like the family of an

overachiever, these locals may care about him but have become weary of

his accolades. But this family member belongs not only to us or to this

nation. “This guy represents standing up for what is right,” says

Hewitt, who has accompanied international visitors on the water trail.

“A lot of these places have strife going on, so Lincoln’s courage is a

big thing to them.”

After

determining we are not deceiving the eagle within our makeshift blind,

we move on. As we near the end of our journey, Hewitt mentions that

while the Lincoln connection to the trail should increase interest in a

waterway already abounding with natural history, some local people are

tired of hearing about Lincoln’s exploits. Like the family of an

overachiever, these locals may care about him but have become weary of

his accolades. But this family member belongs not only to us or to this

nation. “This guy represents standing up for what is right,” says

Hewitt, who has accompanied international visitors on the water trail.

“A lot of these places have strife going on, so Lincoln’s courage is a

big thing to them.”

And

there is no doubt that there is a sense of history on the Sangamon

River that cannot be found in the inanimate objects of a museum. In a

way, we too can sense what Lincoln experienced. Conversely, one wonders

what Lincoln would think if he could wander the streets of Springfield

today. Surely the landscape and lifestyles would be all but

unrecognizable.

Yet

in a boat on the Sangamon, life might still seem familiar to him. The

river is changed, of course, as rivers always change – picking up soil,

dropping it and channeling new pathways.

Yet

in a boat on the Sangamon, life might still seem familiar to him. The

river is changed, of course, as rivers always change – picking up soil,

dropping it and channeling new pathways.

But

Lincoln would surely recognize his river in its ever-changing

appearance, the river he spoke of when he made his first political

announcement at the age of 23:

Finally,

I believe the improvement of the Sangamo[n] River, to be vastly

important and highly desirable to the people of this county; and if

elected, any measure in the legislature having this for its object,

which may appear judicious, will meet my approbation, and shall receive

my support.

Your friend and fellow-citizen, A. Lincoln

New Salem, March 9, 1832

Jeanne

Townsend Handy of Springfield has been writing about the natural world

and environmental issues since 1999. She may be reached at www.jthandy.com.