Going the mile

Springfield – a mecca for motorcycles

SPORTS | Bruce Rushton

It is, really, very simple.

Apply throttle, turn left every 10 seconds or so and forget about the brakes. Boiled down, that is the essence of racing motorcycles on dirt tracks. You don’t have to be big or tall.

“It’s fingertips and toes,” says Steve Morehead, a retired racer who works as a race director for the American Motorcycle Association, presiding over competitions at the top tracks in America, including the oval at the Illinois State Fairgrounds in Springfield. “It’s all ballet. Finesse.”

Beyond the obvious need for nerve, you must be in excellent physical condition. You must have an understanding family that doesn’t mind when you travel thousands of miles to risk your life. It helps to have a job with flexible hours that pays a lot of money, considering that a flat track bike can cost more than $25,000, the prize for first place is considerably less than $10,000 and orthopedic surgeons don’t work cheap.

Making a living by racing motorcycles on fairground racetracks is tough, but dying is easy. Since the 1920s, at least 109 riders have been killed racing motorcycles on dirt tracks around the nation, with 10 men taking the last lap of their lives in Springfield, which boasts the fastest dirt track on the planet, thanks to short straightaways and relatively gentle turns that render brakes superfluous and encourage speeds as fast as 130 mph.

On smaller, less expansive tracks, riders must let off the gas, perhaps even apply brakes, but not at Springfield. It is full-throttle-crouched over until a turn approaches, then sit up to catch the wind while easing back to half-throttle or so, then crank it back up once past the curve’s apex.

Simple. The gas may never go off at Springfield, but the laws of physics are always in force. Attached to frames and forks, motorcycle wheels become gyroscopes at anything faster than 5 mph, and so Newton would be fascinated by a flat-track racer in full turn, front wheel pointed away

from direction of travel while rear wheel slides, the back tire at once a brake and a rudder that determines direction as the rider uses throttle and position in the saddle to coax the sliding bike along the right path. The optimal line of travel on a brown dirt track can turn blue from transfer of rubber, and nowhere is the so-called blue groove bluer than in the turns, where, if you venture close enough and listen very carefully, you can hear the slide of tires against the considerable roar of twin-cylinder motors.

“You’re actually peeling the rubber off the tires,” Morehead says.

Making the unimaginable even more unimaginable is the left foot, which skims along the track’s surface in the turns, sole protected by a strapped-on steel plate called a hot shoe. In addition to helping the rider maintain balance, getting the left foot off the foot peg and onto the ground allows the rider to dip the bike extralow toward the infield so that the handlebar tip sometimes goes south of a rider’s knee.

“It’s like stepping out of your car on the freeway at 70 mph,” Morehead says.

And Springfield is the mecca.

Almost like asphalt

NASCAR has Daytona. Formula One has Monaco. Indianapolis is famed for open-wheel racing on oval tracks. Springfield ranks with all these cities when it comes to a uniquely American form of racing.

During the years leading up to World War I and into the Roaring Twenties, motorcycle racing in the United States was popular on wooden tracks. Built from two-by-fours and running as long as a mile-and-a-quarter with banked turns that enabled speeds surpassing 100 mph, the so-called motor dromes were dubbed “murderdromes” by the press, owing to the frequency and severity of crashes.

Dirt tracks, typically on fairgrounds and often in the Midwest, became the home of motorcycle racers by the Great Depression, with races in Springfield starting in 1937. The capital city quickly became known as the place

to win, with the coveted Number One number plate awarded for the entire

racing season to the rider who won in Springfield. In 1954, a points

system was established so that the Number One plate and official

championship was awarded to the rider who compiled the best record over

an 18-race schedule, but Springfield remained special.

Beyond

the track’s dimensions, the claylike surface is notorious for being

smooth, and smooth equals fast. It is distinctly different from the

surface used for harness racing at the fairgrounds in that a layer of

loose dirt a halfinch thick is atop the track when the ponies compete.

It’s called a cushion, and that’s bad for motorcycles that already slide

just fine without any loose dirt.

Beyond

the track’s dimensions, the claylike surface is notorious for being

smooth, and smooth equals fast. It is distinctly different from the

surface used for harness racing at the fairgrounds in that a layer of

loose dirt a halfinch thick is atop the track when the ponies compete.

It’s called a cushion, and that’s bad for motorcycles that already slide

just fine without any loose dirt.

“This

has almost no cushion,” says Mark Burtle as he takes a break from

watering the track last Friday, one day before the first of back-to-back

Springfield Miles on Saturday and Sunday. “It’s almost like asphalt,

but better. We get a lot of photo finishes here.”

Burtle,

who works full time for the state at the fairgrounds, has been

preparing the track for Springfield Miles for 27 years. It is largely a

job of moisture management, and he constantly checks the weather

forecast. Preparation for this year’s race began five days before the

first heat. During the final two days before racing started, Burtle

dumped 70,000 gallons of water on the track.

On

race day, Burtle will add calcium chloride, which helps the track

retain moisture, to the water applied to the surface. A track that

becomes too dry is prone to cracking, Burtle says, and racing on a

cracked surface is like racing atop loose jigsaw puzzle pieces. A

just-right surface is almost tacky – close your eyes when you kick your

foot atop a properly prepared track and you would never know that you

were standing on dirt.

When

conditions are right, the Springfield track allows for classic

motorcycle racing. Warm-ups and eight-lap heats and the better part of

the main 25-mile event are used to test and gauge the competition,

figure out which riders are fastest and put yourself in a position to

take off when they do. Anything can happen, but the final five miles of

the main event are often marked by positioning and drafting other bikes

and thinking ahead until, ideally, you accelerate out of the lead bike’s

slipstream at the finish, just in time for your tire to cross the line

first.

“It’s a mind game,” Morehead offers. “It’s like playing high-speed chess.”

History and infamy

Famous as the Springfield Mile is, it was not always welcome in its hometown.

Now

held on Memorial Day weekend and again over the Labor Day holiday, the

Springfield Mile was once held on the last day of the state fair, and

the crowds did not always mix well. Thousands of race fans, many from

out of town, spilled over into downtown bars at day’s end.

“The

police would walk in groups of four to six,” recalls Springfield Mayor

Mike Houston. “They didn’t have billy clubs. They had much longer

sticks, and they had helmets on.”

By the mid-1960s, motorcyclists had a bad image, fueled in part by the 1966 publication of a bestselling book, Hell’s Angels, by Hunter S. Thompson. The Springfield Mile came to an end that same year, after a race for the ages.

The race then was 50 miles long, twice the distance of today’s final, and the winner,

often as not, was decided

by mechanical failure, engines in that day not being known for

durability when run flat out for any appreciable time. Sure enough, the

leader, then nearly 20 seconds ahead of the pack, blew a piston with one

lap to go. Four riders had a chance and played nip-and-tuck all the way

to the finish, with Gary Nixon finally taking it at the line without

his protective steel hot shoe, which had come off 10 laps earlier. He

collected $3,230 in winnings before a cheering crowd of 30,000.

Less

fortunate were Bill Corbin and Rick Vetter, who died in a five-bike

wreck during an amateur event prior to the showcase race. It remains the

deadliest day in the history of the Springfield Mile, which culminated

that year with 70 arrests for disorderly conduct, drinking offenses and

moving violations as rowdy spectators moved from the fairgrounds to

pubs. There was no race for the next 15 years.

Motorcycles

didn’t return to the fairgrounds until the early 1980s, when Stan Hall,

owner of Hall’s Harley-Davidson on Dirksen Parkway, and other race

backers convinced authorities to allow a Labor Day charity ride to

benefit children with muscular dystrophy. For a dozen hours straight and

through the night, just one rider at a time was allowed on the track,

with people pledging as little as a penny per lap for charity. Hall

still remembers the fastest lap time.

“Forty-seven seconds,” he says with an obvious gleam in his eye.

Not bad, considering it was the middle of the night on a track with no lights.

The glory years

The

charity ride proved the wedge that reopened the fairgrounds to real

racing. Within two years, Springfield was back on the national dirt

track circuit just as the sport was approaching a zenith.

There

were 20 or more top-level flat track races each year during the 1980s

and 1990s, with coverage on ESPN and lots of money from RJ Reynolds,

which had naming rights to the circuit dubbed the Camel Pro Series. Top

riders raced for teams owned by manufacturers, notably Harley-Davidson,

and didn’t need day jobs. With purses as high as $100,000 for a single

race, the Springfield Mile was the richest stop on the circuit. There

was talk of establishing a dirt track hall of fame in the capital city.

More than two dozen riders were inducted, but the hall was never built

as interest in dirt track racing waned and ESPN found other sports to

feature.

This year,

the circuit includes just 13 races, the Springfield purse was $50,000

and there was plenty of room to sit last weekend in the fairgrounds

grandstand. Many of the 43 riders in Springfield had to cobble together

sponsorships to pay the bills, many of them working regular jobs during

the week.

Dan Ingram,

who at 48 is one of the oldest racers on the circuit, works as a union

construction worker in Indiana when he isn’t crisscrossing the nation

racing motorcycles. Like most of his colleagues, he started riding

young, when he was less than five years old. He reached the top echelon

of dirt track in 1983 and won three races going handlebar-to-handlebar

with the best until a horrific crash at the 1993 Springfield Mile, when

he lost it in a turn and hit a wall.

“I

almost died,” he recalls. After coming out of a coma and recovering

from a broken neck, Ingram retired, but racing was always on his mind.

He began running and working out a few years ago, getting in shape for a

return to the track. Despite some initial concerns from friends and

family – and he says that it wasn’t easy telling those who love him that

he was coming out of retirement – he started racing again last year.

Why? “I just never lost the love for it and I wanted to see if I could still do it before it was too late to try,” he offers.

Ingram

and others who know what it’s like to go 130 mph down the straights,

then bump handlebars and knees while side-by-side in the corners, say

they do it because they love the competition or the challenge or the

adrenaline or

all three. But Ingram is realistic.

“If you’re not scared, you’re an idiot,” he says.

“It’s who I am”

Motorcycling

is such a way of life for flat track racers that getting married on

Sunday in front of the grandstand seemed perfectly normal for Jared

Mees, who proposed to fellow racer Nichole Cheza a year ago at the

Springfield Mile.

“She

races, I race, everyone around us races,” Mees explains about the

couple’s choice of wedding venues. “Why not get it on?” Mees, who

finished first in the overall standings last year and so rides with the

coveted Number One plate on his bike, often rides in the same events

with his bride, who suffered a serious back injury during a crash last

year in Springfield while Mees finished fourth. She walked away from a

spectacular wreck earlier this year in Indianapolis, but her bike was

cut in half by another rider who hit it after she went down.

“She’s been through crashes,” Mees says. “It worries me. I try to block it out.”

Cheza,

the new bride, was a fan favorite in Springfield, judging by lines for

autographs and cheers that rose whenever her name was announced on the

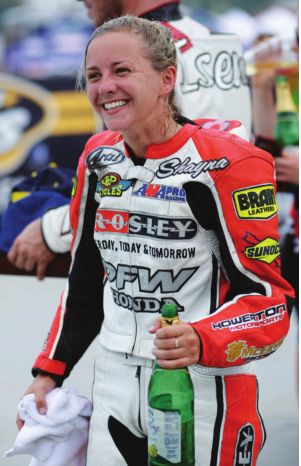

PA system. But Shayna Texter was the It Girl of the Springfield Mile

this year, dominating preliminary heats and winning both main events in a

new rider classification created for racers just starting out on

twin-cylinder bikes on mile-long tracks.

Texter

won her class’s 12-lap main event on Saturday by a Secretariat-sized

11.4 seconds and rode the fastest lap of any rider that day, regardless

of class. Her margin of victory was more than four seconds on Sunday,

still huge by Springfield standards. The weekend marked the first time

that Texter had ever raced a twincylinder bike on a long track. She

usually races smaller single-cylinder 450cc bikes.

Texter

won her class’s 12-lap main event on Saturday by a Secretariat-sized

11.4 seconds and rode the fastest lap of any rider that day, regardless

of class. Her margin of victory was more than four seconds on Sunday,

still huge by Springfield standards. The weekend marked the first time

that Texter had ever raced a twincylinder bike on a long track. She

usually races smaller single-cylinder 450cc bikes.

“I

always dreamed of winning the Springfield Mile,” Texter said after

Saturday’s win. “Hopefully, I’ve proved to some people today I can ride a

twin as good as a 450.”

Skepticism

would be understandable, given that Texter, a 22-year-old college

student from Pennsylvania, stands five feet tall and weighs between 95

and 100 pounds, less than a third of the weight of a dirt track racing

motorcycle. Sure, it’s about finesse, but Texter says that heavier

riders have an advantage on some tracks because it’s easier for them to

maneuver the rear tire into proper position in the turns. But any such

advantage disappears on smooth tracks like Springfield, she says.

Texter,

who is studying sports management and taking courses online, comes from

a family of racers. Her father, who died three years ago, raced dirt

track bikes and ran a Harley- Davidson shop after retiring from the

track; her grandfather raced sprint cars on dirt. Her reason for racing

is simple.

“It’s who I am,” says Texter, who started racing a decade ago.

Texter’s

sweep of the weekend’s races earned her $2,000, a grand for each win.

Brandon Robinson, who swept the main races in the top class plus won two

shorter competitions, also won every event in his class and took home

$17,000 in prizes, the best possible finish. It was another step on a

comeback from his rookie season in 2009, when he went down in

Indianapolis, bounced off a light pole and landed outside the track,

suffering a shattered back, pelvis and hip. It was four months before he

could walk again.

He was back on the bike the next year.

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].