Gunning for change

Concealed carry is coming to Illinois

GUNS | Patrick Yeagle

I first realized something was wrong when I noticed that everyone else was running the other way.

I was an undergraduate in my senior year at Northern Illinois University in DeKalb, walking across the snowy campus on Valentine’s Day, 2008. The usual random movement of the crowd seemed to have become a stampede away from one building: Cole Hall, a multi-purpose lecture hall near the center of campus. It was there that a lone gunman had opened fire with three handguns and a shotgun in a crowded oceanography class, killing five students and wounding at least 22 other people before killing himself.

I vividly remember seeing the fear on peoples’ faces as they fled, drowning in confusion, chaos and terror. As the death toll became apparent over the next couple of days, the panic that gripped the campus turned into an overwhelming collective dismay. How could this happen on our quiet campus? Why would anyone commit such a horrifying, senseless crime? The unanswered questions piled up, and the only thing to do was grieve together.

It didn’t take long for political pundits to appropriate the tragedy as fuel for their debates on guns. Some claimed this was a prime example of why no one should have guns. Others posited that if someone else in that lecture hall had been armed, the gunman would have been stopped much sooner. Would either hypothesis have prevented the deaths of those five innocent students? It’s impossible to tell.

The same scenario has played out several times as mass shootings continue to plague the United States, and Illinois is about to embark on an experiment testing the notion that allowing regular citizens to carry firearms can curtail or prevent the devastation that has become all too common. A federal appeals court ruled in December that Illinois’ current law banning the concealed carry of firearms is unconstitutional and ordered state lawmakers to enact a new law with “reasonable limitations” that allows the carrying of guns in public. It’s almost certain that concealed carry in some form will become law in Illinois by the court’s deadline of June 9.

What form concealed carry will take is still unclear. The new law could result in citizens carrying firearms regularly, or restrictions could make carrying impractical and cumbersome. Either way, the introduction of weapons into the daily lives of Illinoisans is sure to change aspects of the state’s culture. Will an argument over a parking space turn into a gunfight, or will the knowledge that others may be armed provide an incentive for added civility? We’re about to find out.

The holdout

Illinois is the only state in the U.S. which doesn’t allow citizens to carry concealed firearms in some manner. Most states have a “shall issue” law, in which a license is required to carry a firearm, and authorities must grant the license unless an applicant doesn’t meet certain specific criteria. Ten states, such as New York and Rhode Island, have what is known as a “may issue” statute, in which authorities may – but don’t have to – grant a license, usually at the discretion of the local sheriff. Alaska, Arizona and Vermont have no restrictions on residents carrying concealed firearms, and no license is required. States vary widely with regard to allowing non-residents to carry concealed firearms with or without a permit.

Within the Illinois General Assembly, the issue of guns divides Democratic lawmakers along geographical lines, while Republicans tend to vote together in favor of relaxing gun restrictions. Although there are exceptions, most Democratic legislators from Chicago and the closer suburbs tend to oppose measures that make guns more accessible. Meanwhile, legislators from the outer suburbs and downstate tend to support relaxing restrictions on guns.

The reason for the divide has to do with how guns are used in particular settings. In more metropolitan areas like Chicagoland, guns tend to be associated with crime – often because of gang activity and the illicit drug trade. That leads many lawmakers and citizens to see guns as an impetus for violence in their neighborhoods.

In more rural areas, guns are typically used for hunting and recreation, so lawmakers and citizens tend to be more comfortable with guns and even see them as a guarantee of freedom.

During a rancorous debate on concealed carry in the Illinois House of Representatives on Feb. 26, one lawmaker summed up what some pro-gun downstate residents feel toward Chicago when it comes to guns.

“I love you folks in Chicago,” yelled Rep. Jim Sacia, R-Pecatonica. “You’re the ones that have the problem. You have a runaway gun problem. Don’t blame

the rest of us; this isn’t about Democrats. It’s not about Republicans.

…Here’s an analogy, folks. I ask you to think of this: You folks in

Chicago want me to get castrated because your families are having too

many kids.”

The

comment raised controversy on the House floor because it was

interpreted by some lawmakers as having racial undertones, and Sacia

defended his statement as being only an analogy. Still, it illustrates

the vastly different views between pro-gun and anti-gun advocates.

“Illinois

is a perfect example of a state that is going to show these vast

differences,” said Rep. Ann Williams, a Democrat from Chicago’s north

side. “We have an incredibly dense urban area that I represent, where

our houses are located on 25-foot lots, as opposed to downstate, where

you have much more space between people. There is a definite difference.

I hear from many constituents, and many of them don’t like guns. It

hasn’t been a part of their culture, they didn’t grow up being around

firearms, and they’re concerned any time they hear about guns being in

their community in any way, shape or form – legal or otherwise.”

The culture of guns

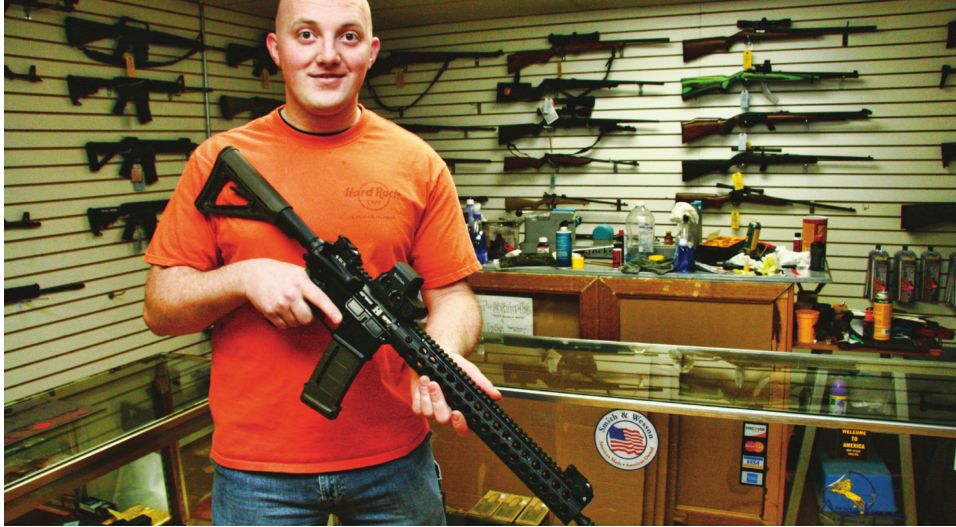

John

Jackson says he has been shooting guns his entire life. Jackson is

co-owner of Capitol City Arms Supply Gun Range in Springfield.

“I didn’t play baseball or soccer,” Jackson said. “I shot competitively.”

On

a typical day at Jackson’s shop, a handful of regulars can be found

hanging around, talking about the topic of the day. The reverb of

gunfire pierces the walls of the firing range and punctuates the chatter

of patrons, who barely seem to notice the random muffled pops.

Occasionally, someone will proudly show off a new gun or even a piece

they’ve built themselves. For this mostly male crowd, guns are a social

center point, an excuse to shoot the breeze with like-minded people.

Jackson

says the volume of new shooters has increased “tenfold” because of

talks in Washington, D.C., about restricting firearms in response to the

December 2012 mass school shooting in Newtown, Conn.

“People

don’t really think of their rights until they’re threatened,” Jackson

said. “People believe it is their right to do it [carry a weapon].”

According to Jackson, owning and carrying guns should be seen as both a right and a responsibility.

“People

are responsible for their own safety,” Jackson said, summing up a

common attitude among firearm owners. He says many gun owners don’t

believe they can rely on the police to save them from a violent attack.

“The police are there to clean up the mess. When seconds count, the

police are only minutes away.”

Rep.

Ken Dunkin, a Democrat who represents part of Chicago’s south side,

agrees that people should be able to protect themselves, and he says he

doesn’t feel a “negative disposition” toward guns. However, he’s not

ready to grant concealed carry licenses to just anyone who asks. Dunkin

filed an amendment to the current concealed carry legislation requiring

anyone who carries a firearm to purchase a $1 million liability

insurance policy, but he also voted in favor of an amendment that would

make Illinois a “shall issue” state.

“With

Chicago being so not a part of the conceal-and-carry culture, it (the

idea of concealed carry) is a bit of a shock for some,” Dunkin said. “If

you live in a tough area like I do, it’s important to protect yourself

before the police get there because they come when it’s over with to do a

report. So we need to be conscious of that, but we also need to be

conscious that the proliferation of guns doesn’t necessarily add the

value that we want.”

Rep.

Ann Williams says she’s not out to ban all guns or even stop concealed

carry, contrary to popular stereotypes of Chicago Democrats. She even

says her father and brother are members of the National Rifle

Association, which she says “leads to some interesting conversations

around the dinner table.” Williams filed a pair of amendments to the

concealed carry legislation that would ban guns at places that sell

alcohol and at public gatherings like rallies and protests. Whether the

presence of weapons in everyday life will escalate arguments into

shootouts or spur more respectful behavior is unknown, Williams says.

“Common

sense would tell you that if you have a large number of people in a

crowded space and then you add loaded weapons into the mix, you have to

be concerned about the safety issues there,” Williams said. “You throw

in alcohol in a bar or a street fair setting – we all know that alcohol

impairs peoples’ judgment – and that is an even greater concern.”

Eric

Smith, chief of police for the Sherman Police Department, says he was

surprised to find out from police in Pittsburgh and Dallas – both of

which have had concealed carry for years – that the introduction of guns

hasn’t made much difference in crime rates either way. Smith is a past

president of the Illinois Association of Chiefs of Police, and he helped

convince the organization to support concealed carry legislation in

Illinois. He says the concealed carry experience in other states has shown that fears of “shootouts on every corner” are overblown.

“I

do not believe that we’re going to have people getting angry and

pulling out their guns,” Smith said, adding that proper training is a

crucial component of concealed carry.

“Training

teaches people that they’re not out there to save the world or be law

enforcement; that’s our job,” Smith said. “They’re out there to protect

themselves.”

Sandy

Baksys of Springfield says she became concerned about the prevalence of

guns following the school shooting in Newtown, Conn. She has become an

activist, staging a demonstration last week at the Illinois Statehouse

about gun safety and keeping guns out of the hands of criminals.

“Newtown

crossed a line that was so emotionally and morally repugnant – 26

little kids and teachers shot to pieces – that everyday people just

couldn’t go about their business anymore and not do anything,” Baksys

said, explaining that she believes pro-gun groups should take the lead

on keeping guns out of the wrong hands. “We are not trying to take away

anybody’s guns or violate their constitutional rights. But in light of

everything that’s happened before and after Newtown, we do see a direct

connection between gun safety and public safety.”

Baksys

says her focus on guns is broader than just concealed carry, but she

believes specific restrictions are needed to prevent concealed carry

from souring into violence. Among the requirements Baksys supports is a

liability insurance policy for anyone carrying a concealed firearm “to

protect any innocent member of the public who gets shot by that gun.”

While

Baksys says she doesn’t believe anyone other than law enforcement or

security personnel should be able to carry weapons, if concealed carry

is inevitable in Illinois, she supports the “may issue” approach, in

which local sheriffs have the final say in deciding whether to grant

concealed carry permits. She also supports background checks for every

gun sale and mandatory reporting when a gun is stolen.

“In

my view, a ‘too loose’ concealed carry law would dramatically increase

the potential for legally owned guns to be lost, misplaced or stolen –

and fall into the wrong hands,” Baksys said.

The legislation

On

Feb. 26, the Illinois House spent more than nine hours debating

amendments to House Bill 1155, the main concealed carry bill sponsored

by Speaker Michael Madigan, D-Chicago. Lawmakers approved amendments

that would ban guns from schools, child care facilities, government

buildings, gaming facilities, libraries, stadiums, amusement parks and

aboard public transport. The same day, they voted down amendments to the

bill which would ban guns at colleges and universities, places serving

alcohol, public gatherings like rallies and protests, and places of

worship.

Another

18 amendments remain to be voted on, including Dunkin’s amendment

requiring a $1 million liability insurance policy, an amendment making

it a felony to not report a gun theft, and a requirement that gun owners

keep records of any guns they sell.

In

its current form, the bill to legalize concealed carry in Illinois

would make this a “shall issue” state with a handful of prohibitions on

where guns could be carried. Advocates of concealed carry prefer “shall

issue” states because such states tend to issue licenses more

frequently, while “may issue” states can effectively ban concealed carry

if local authorities readily deny licenses.

However,

the main amendment within the concealed carry bill contains provisions

that would allow a local sheriff to object to a concealed carry

application originating in his or her county. Sponsored by Rep. Brandon

Phelps, D-Harrisburg, Amendment 27 calls for a criminal background check

for each concealed carry application, and no one who is disqualified

from owning a firearm for mental health reasons would be granted a

concealed carry license.

Phelps’

amendment is important because it would establish Illinois as a sort of

hybrid state – “shall issue” in name, but with local oversight similar

to “may issue” states. The amendment is seen by many in the Statehouse

as a reasonable compromise, and it passed the House by a vote of 68-47

on Feb. 26, with several downstate Democrats voting for it.

Rep.

Michael Zalewski, D-Riverside, voted against the “shall issue”

amendment. Zalewski sponsors several amendments that would restrict

where guns could be carried in Illinois, as well as a separate amendment

to make Illinois a “may issue” state. Zalewski says he isn’t opposed to

concealed carry in principle, as long as there are restrictions to

protect public safety. A former prosecutor, Zalewski says he doesn’t

expect carnage when concealed carry becomes law.

“Advocates

of concealed carry say those things don’t happen, and I tend to say

‘Yeah, you’re right,’ but we do have a gun crime problem in Chicago,” he

said. “People whom I’ve talked to who are responsible gun owners say

it’s an issue of personal safety for them, so that they can protect

themselves. But, I also know that there are people who have an

expectation of safety when they enter a school or a park or a government

building. That’s where the balancing is. It’s personal safety versus

expectation of safety of the surrounding community.”

One

of the most contentious unresolved issues remaining is whether to allow

units of local government to place further restrictions on concealed

carry. Illinois has a constitutional guarantee of “home rule,” meaning

municipalities of more than 25,000 people can pass ordinances regarding

taxes and regulations, with certain limits. If state lawmakers opt to

preempt home rule power, cities like Chicago would not be allowed to ban

concealed carry within city limits, which would be a major victory for

gun advocates following years of court battles over the city’s previous

ban.

For Illinois

lawmakers mulling concealed carry, the question is no longer yes or no,

but rather how to go about it. Concealed carry bills have come up before

the Illinois General Assembly for several years running, failing each

time. But with the federal appeals court calling for a concealed carry

law, the decision is now largely out of state lawmakers’ hands. The goal

for lawmakers who oppose concealed carry seems to be restricting the

activity enough that carrying concealed will be inconvenient, but not so

much that the federal appeals court deems the restrictions

unconstitutional.

Back

at Capitol City Arms Supply Gun Range in Springfield, one female

shooter who didn’t want her name used carefully fired through two clips

of ammunition from a .45 caliber handgun while wearing pink ear

protectors. She says she enjoys shooting and would feel safer if she

could carry a weapon for self-protection. The ubiquity of cell phones is

of little comfort to her because of the time it takes to call the

police, report an attack and wait for an officer to arrive.

“Women

are considered to be more susceptible to crime,” the female shooter

said. “Why am I not allowed to defend myself? … Having the ability to

have that firearm makes me less of a victim. I stand a fighting chance,

whereas before, I didn’t.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].

For more info on concealed carry legislation in Illinois, see this story online at www.illinoistimes.com.