A history of Springfield romances

Six love stories to put you in the mood

HISTORY | Erika Holst

Love to last a lifetime

Sarah Blanchard and Stuart Paterson When Sarah Lee Blanchard of Springfield entered the University of Michigan in the fall of 1961, she had no idea she would cross paths with the love of her life. In fact, she thought she had already found him: the dark-haired, brown-eyed beauty was going steady with her high school sweetheart, a 6-foot-8-inch star basketball player who had led Springfield High to the state championship in 1959 and was now captain of the University of Michigan basketball team. Sarah had spent two years at Mills College in California but had transferred to Michigan to be closer to him.

Fate intervened in September of 1962, when the cousin of one of Sarah’s roommates invited himself over to their apartment to watch a football game on their television. Stuart Paterson was a 22-year-old first-year graduate student in the economics department. More than 50 years later, he can still recall the green skirt and soft, cream-colored sweater Sarah had on when he first laid eyes on her. She was beautiful, Stuart thought. And though he envied the man who would make her his wife, he didn’t dream at that point that it would be him. Stuart had purchased an engagement ring for his college sweetheart and was planning to propose at Christmas.

Fate intervened again, first when Stuart received a “Dear John” letter from his girlfriend in November, then when Sarah and her boyfriend broke up over the holidays.

Sarah and Stuart started dating in January of 1963. By August, they were engaged, and by December, they were married. They spent 48 beautiful years together, parted only by Sarah’s death in September, 2011. Looking back on the life he shared with his wife, Stuart reflected, “During our marriage, love and respect deepened as we raised three boys and grew in our chosen professions. We gave each other space and independence. And we thought of ourselves as lovers and best friends.”

After Sarah died, Stuart composed the following tribute to her, moved by a heart filled with love for the woman who made his life worth living: SARAH LEE BLANCHARD PATERSON June 30, 1941-Sept. 17, 2011 “Where-e’er you walk, cool gales shall fan the glade, “Trees, where you sit, shall crowd into a shade, “Where-e’er you tread, the blushing flow’rs shall rise, “And all things flourish where-e’er you turn your eyes.” – Alexander Pope, “Summer”1709 Every day we were together I told Sarah, “I love you.” And each time she said, “I love you, too.” These were the last words we said to each other.

Almost every day I told her she was beautiful and she replied, “You’re crazy, but I’m glad you think so.”

And almost every day I told her she was the most wonderful person who ever lived and she would say, “You’re crazy, but I’m glad you think so.”

Well, she was beautiful. And she was, for me, the most wonderful person who ever lived.

Sarah was loving, kind and forgiving. She was thoughtful, intelligent, and wise. She was disciplined, hardworking and loyal. She was caring and thoughtful of others. She was playful, joyful, and fun.

She was discerning. When she told me someone was a friend I knew immediately that they had those qualities that are to be treasured.

She loved her sons and their families beyond words. She was happiest when she was with them and especially her grandchildren.

In my eyes Sarah was perfect. And she would say, “You’re crazy, but I’m glad you think so.”

I do know beyond any doubt that “All things flourished where-e’er she turned her eyes.”

Sometimes love really does last a lifetime.

Ever full of love for you

Mary Nash and John T. Stuart John

T. Stuart’s new law partner, Abraham Lincoln, moved to town in April of

1837. As momentous as this event was to the history of Springfield, at

the time, 29-year-old John had other things on his mind: he was

absolutely smitten with a lovely young woman in Jacksonville, and on his

last visit there she had accepted his proposal of marriage. When he

returned home he put pen to paper to express his feelings to his future

bride:

… The word wife and connected with you Mary fills my heart with gladness.

Since

my return from Jacksonville (and a rough ride it was) in thought and in

feeling, I am an altered man. I now feel as if I had something worth

living for, One dear object to love (and will you let me say it?) one by

whom that love is returned.

You

know I have been a day dreamer but my day dreams (when I have time to

dream) are changed; they were always bright, but were then Fancy’s

offspring, and without an object, I no longer build airy castles in

Fancy’s bright land without a “local habitation or a name.” I now think

and dream of my own dear Mary…(April 14, 1837).

Mary

was the 20-year-old niece of Judge Samuel D. Lockwood, then one of the

Supreme Court justices of Illinois. Orphaned as a teenager, Mary had

gone to live with her distinguished uncle and aunt in Jacksonville. It

was there that she first met John T. Stuart, a handsome, well-educated,

successful young lawyer and Whig politician. John was charmed by Mary’s

intelligence, her independent spirit, and her fine manners. During the

six months that elapsed between their engagement and wedding, his

thoughts often turned towards Jacksonville:

“The

time passes off to me very heavily, my thoughts are in Jacksonville, I

picture to myself how you looked and what you said when I saw you and

until Wednesday I will imagine what you will say… I leave you to imagine

all I would say were I to write all the feelings of my heart, it is

ever full of love for you and I now send it to you. Good night I will

now go and gaze at the stars and think of Mary….” (July 31, 1837) As

the weeks crept by, John grew increasingly impatient to leave his

bachelor days behind and commit himself to his beloved Mary. Mary, in

turn, seems to have suffered cold feet in anticipation of their wedding:

…Your

presence is daily becoming more necessary to my happiness and I am

sometimes surprised at myself (old bachelor as I am) to find how my

every thought and feeling have some relation to my beloved Mary. No plan

is laid for the future in which you do not bear a prominent part, no

hope springs up that is not brightened by your image. You peep from the

windows of all my airy castles. The time I hope is near when I shall

feel no more the sorrows of absence, six weeks will soon roll round

again and then – but I remember that subject, the wedding day and

becoming a wife, gives you a long face and had better stop it….(Sept. 15,

1837) Whatever reservations Mary had about marriage were fleeting, and

she and John wed on Oct. 25, 1837. Over the course of their marriage they had seven children and buried two. They remained devoted to each other until parted by John’s death in 1885.

The only man for her

Lydia Matteson and John McGinnis Lydia

Matteson seemed to have it all. The daughter of Illinois governor Joel

Matteson (1853-1857), she had wealth and the privilege of moving in

Springfield’s most elite social circles, a fine education from

Monticello Female Seminary in Godfrey, Ill., and personal charm and

beauty. This attractive young woman had no shortage of suitors – rising

young men who plied her with gifts and love letters. By the time she was

20 years old she had been courted by “the best in the country,”

according to her sister, Clara, among them John A. Logan, the Illinois

state representative who would go on to become a celebrated general

during the Civil War.

But

Lydia had eyes for only one man. Her heart belonged to John McGinnis,

president of the Quincy Bank in Quincy. The young man returned her

affection and asked her to be his wife. Her parents, however, refused to

consent to the engagement. No explicit reason for this refusal has been

recorded, although an item in the Aug. 19, 1852, Illinois State Journal might

shed some light on the matter: “On the 13th, there was a resolution in

the Senate for the arrest of John McGinnis for refusing to answer

questions by the committee on frauds.” The alleged fraud, it seems, had

to do with an appropriation of $300,000 for clothing for soldiers in

California, New Mexico and Oregon, and an additional $20,000 for “the

introduction of camels on the plains.”

Lydia

was brokenhearted and determined that if she could not have the man of

her choice, she would have no one at all. She retired to her room and

refused to attend any of her parents’ lavish receptions, refused all

invitations to dinners and parties, and refused all advances by other

prospective suitors. John, in the meantime, remained steadfast in his

devotion to her. Finally, her parents had no choice but to give in and

grant her permission to marry the man of her dreams.

Many

people in town, Mary Lincoln among them, hoped that the Mattesons would

use the wedding as an excuse to throw one last grand, public party

before the governor left office and vacated the mansion the following

January. “The hour of her patient lover’s deliverance is at hand,” Mary

wrote her sister a few days before the wedding. “Some of us who had a

handsome dress for the season thought it would be in good taste for

Mrs Matteson, in consideration of their being about to leave their

present habitation, to give a general reception. Lydia has always been

so retiring that she would be very averse to so public a display.”

The

wedding took place at the Governor’s Mansion on Nov. 27, 1856 – the

first wedding ever held in the new official residence, which was only

completed a year prior. John and Lydia went on to have five children and

enjoy 42 years of marriage before Lydia died in 1898. John followed in

death three years later.

All the world to me

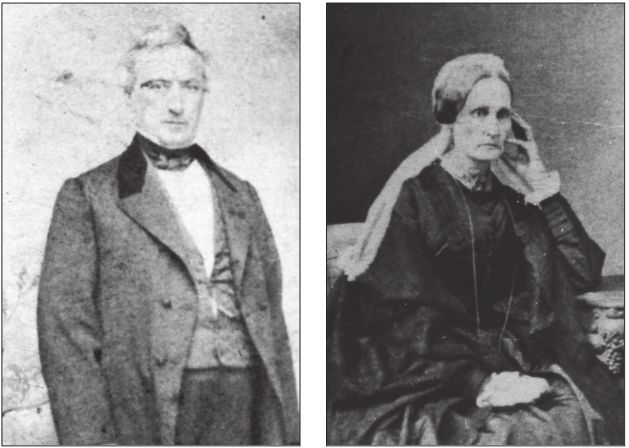

Stephen T. Logan and America Bush Lincoln’s

second law partner, Stephen T. Logan, is remembered as a formidable

legal mind with a crabby temperament, but history often forgets that he

was a tender and devoted husband to his wife, America Bush.

Stephen was born in Franklin County, Ky., on Feb. 24, 1800. His mother died when he was two years old, and his father died when he was 21. By that time Stephen was already making his own way in the

world. He had moved to Glasgow, Ky., to study law under his uncle at the

age of 17 and was admitted to the bar two years later. While there he

became acquainted with a teenager named America Bush, eldest daughter of

the president of the local bank. America was known as a “lady of

refined manners, of unaffected piety and unpretentious benevolence.”

Stephen fell in love with her, and the couple was married in 1823, when

America was just 17 years old.

The

couple became parents to eight children, who appeared at regular

intervals between 1824 and 1845: David, William, Christopher, Mary,

Sally, Stephen, Jennie and Kate. William died at age 6, Stephen died at

age 8 and Christopher died at 21, leaving Stephen and America devastated

but even more mindful of how much they meant to each other. A letter

written from Stephen to America in 1850, after 27 years of marriage,

sheds light on just how much this crusty lawyer loved his family:

My

dear wife, I have got almost homesick and out of all patience here…I do

not think I will ever again for the sake of money undertake any thing

to take me away from home so long. We may not have a great many years to

live together and I feel that it is a higher duty as it certainly is a

greater pleasure to be with you and our children and to endeavor to

comfort and sustain each other than to make any further advance in

worldly prosperity. I hope however that this absence will teach us to

estimate more highly the privilege of being together and that we may as

we ought to have such reflection as may be advantageous to us hereafter.

We may sometime be separated and one of us left lonely and bereaved. I

have often thought of this since I have been here; and how we ought to

prepare for it. Before many years we must both leave this world but I

rest in hope that we shall meet our little boys in a better one.

This place is very dull and uninteresting to me.

I

have indeed as I sometimes think too little interest in any thing out

of my family and I am afraid I am too much bound within them – my wife

and children seem like all the world to me and nothing else worth

attention except as relate to them.

I

shall come home as soon as it is possible for me to do so. Until which

time I commend you all to the care of that kind providence which has so

far preserved us.

Your affectionate husband, Stephen T. Logan America’s

death of a sudden illness in 1868 at age 62 left Stephen heartbroken; a

neighbor reported that “though apparently composed, is in a quiver – a

kind of trembling all the time,” and it was feared that “he too, will

soon be called away.” The funeral took place in the Logans’ home on a

cold, gloomy March morning. To onlookers, Stephen appeared “bowed down

with anguish.” At the end of the service, he declined a last look at his

beloved wife’s body. “Oh no!” he groaned. “I have taken my last look,”

and, as a fellow mourner reported, “sobbed so, that all in the room were

convulsed with weeping, merely from witnessing his deep grief.”

Stephen died in 1880. In his obituary, the Illinois State Journal observed

that “all the affections of his heart were centered on his family, and

he worked for them, not for himself…he was the kindest of husbands and

the most affectionate of fathers. He lived the most of his life in his

family.” He is buried in Oak Ridge Cemetery, surrounded in death, as he was in life, with those he loved best.

Tragic lovers

Eliza Condell and Arthur Wines In

1897, young Cornell University student Arthur Wines gathered his

courage and wrote a letter to the young woman he loved back in

Springfield, declaring his love for her and asking her to be his wife.

Timid, quiet Arthur admitted that he had admired her from afar since

1889, when he was a bashful high school senior and she was 17-year-old

schoolgirl. “Sometimes I have thought I detected something more than

indifference in your face, and manner, but your perfect modesty has

never given me more than an uncertain hope that you could ever care for

anything dearer than friendship for me,” he wrote, yet “If I could know

that your love was the one certain thing in life, I would care but

little for the uncertainty of all the rest.”

Eliza

accepted him, and the couple devised a plan for the future: Arthur

would finish his studies in the summer of 1899, then depart for Alaska,

where his father would secure him a position as a census taker. At the

end of a year and a half, Arthur would return to marry Eliza, and the

couple would start their lives bolstered by the money Arthur earned in

Alaska.

All went well

in the beginning. Arthur bade farewell to his love on July 1 and

departed for Alaska. The couple exchanged affectionate letters full of

heartfelt feelings and excitement about their lives together.

Their

rosy plans for the future began to unravel in September of 1899. After a

grueling month at a mining camp near Cape Nome, the ship transporting

Arthur back to Seattle narrowly escaped shipwreck. As the damaged vessel

limped back to port, supplies were exhausted and passengers were forced

to go without provisions for several days.

Arthur was traumatized.

Several years before, a nervous breakdown had forced him to put his

college studies on hold while he recovered his faculties, and since that

time his mental state had been fragile. Now he felt himself on the

verge of another breakdown. Desperate to be with Eliza, he sent her a

telegram promising to send her money and asking her to travel to Seattle

to marry him immediately.

Arthur’s

father and Eliza’s family intervened, urging the couple to wait until

Arthur was financially and mentally stable before marrying. Disappointed

but resigned, they resolved to stick to their original plan and wait

until Arthur finished his work in Alaska before marrying.

The

strain of his experience on the ship, coupled with the stress of being

far from home, proved too much for Arthur to handle, and he quit his

position and returned to his father’s house in Washington, D.C. While

there he was placed under the care of a physician, who reported that

Arthur was hysterical and incoherent, especially on the topic of Eliza.

Arthur believed that he and Eliza shared a telepathic communication,

that Eliza was on her way to him, that his parents were hiding her from

him downstairs.

Meanwhile Eliza remained steadfast in her devotion to him. “You are not crazy and I am not going

to break our engagement,” she wrote. “It will not be long before God

will allow us to be together. I look up through my tears and the future

when we can be together seems so bright – so happy.”

Meanwhile,

Arthur’s his mental condition continued to deteriorate. His grasp on

reality grew ever more tenuous until he started questioning whether the

people around him were truly real. In desperation, his parents checked

him into a mental hospital. Three days later, Arthur strangled himself

with his bed covering. Eliza was crushed. She lived to be 102 years old

and never married – possibly her heart still belonged to the man she had

given it to more than 70 years before, the man who did not live to

become her husband.

Love is eternal

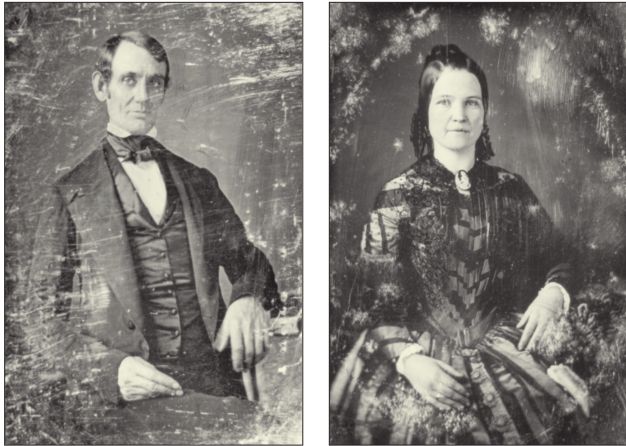

Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd She

came into the marriage with looks, money, and a good name. He brought

nothing but his talent. In the end, he became a legend, and their lives

together became the subject of endless fascination.

Mary

Todd came to Springfield on an extended visit to her sister Elizabeth

in 1839. By 1840, local gossip linked her name with that of a rising

young attorney, Abraham Lincoln. Often they would go out with groups of

their young friends, on picnics, sleigh rides, trips to Jacksonville,

and just as often Lincoln would call on Mary at her sister and

brother-in-law’s house. In many ways they seemed to be opposites – he

was tall and thin, she was short and plump. He was quiet and

introverted, she was bubbly and talkative. He was even-keeled, she had a

quick temper. Yet there were things that they had in common, too. Both

had been born in Kentucky. Both had lost their mothers at an early age – Mary at 6, Lincoln at 9. Both were fond of poetry and

recited stanza after stanza to each other. And both were ardent Whigs,

swept up in the political fervor of the times. Friends remember that

Lincoln was drawn to Mary’s charm, her quick wit, her skill at

conversation, and her good looks. Mary, for her part, saw the potential

for greatness in Lincoln and believed in him steadfastly and from the

very beginning. In the fall of 1840 they seem to have reached an

understanding about marriage.

Then

something happened in January, 1841. No one knows exactly what –

historians to this day still debate the reasons Lincoln and Mary parted

ways, suggesting everything from disapproval on the part of Mary’s

family to Lincoln’s feelings for another woman.

Whatever

the cause for their split, Lincoln and Mary were apart for 18 months.

They were finally reconciled through the intervention of their friends,

Simeon and Eliza Francis, who invited them to their house (without the

other’s knowledge), put them in the parlor and said “be friends again.”

And be friends again they did, only this time in secret. Lincoln and

Mary would sneak off to meet each other at the homes of mutual friends;

not even Mary’s sister, Elizabeth, knew that they had gotten back

together.

By early

fall 1842 it is clear Lincoln had marriage on his mind. He wrote to his

friend Joshua Speed, now newly married and living in Kentucky, pestering

him with questions about marriage – was Speed happy? Was it everything

he had hoped? Was he glad he got married? The answers he got seemed to

satisfy him, and things finally came together for the Lincolns in early

November, 1842.

On

Tuesday, Nov. 1, Lincoln stopped Elizabeth’s husband, Ninian Edwards, in

the street and announced that he and Mary would be getting married that

night at the parsonage. Ninian was understandably flabbergasted – he

had no idea that they were even seeing each other again. After he

regained his composure he protested against the plan of marrying at the

parsonage – it was too close to an elopement, which wouldn’t look right

in society. “Mary is my ward, and she must be married from my home,” he

said. Then he went home and told his wife that she must prepare a

wedding supper.

Elizabeth,

who at that time was seven months pregnant, with a five-year-old and a

three-year-old underfoot, burst into tears when she heard the news. She

was hurt that Mary hadn’t confided in her, and upset that she did not

have enough time to make proper arrangements for a family wedding. She

lamented to Mary that on such short notice she didn’t even have time to

put together a proper dinner – she’d have to send to the baker for

gingerbread and beer. “Well, that’s good enough for plebeians,” Mary

replied, tossing her head.

The

Lincolns were married in the Edwards’ parlor on Friday, Nov. 4, 1842.

The company was small, only about 30 people, and the bride was wearing a

borrowed dress. Recollections vary on Lincoln’s mood during the

wedding. Some people remember that he looked as cheerful as ever, while

others remember him looking like a sheep going to slaughter. But perhaps

his feelings were best expressed by the inscription on the ring that,

when slipped on his bride’s finger, joined her to him for all time:

“Love Is Eternal.”

Erika Holst is curator of collections at the Springfield Art Association.