The Lanphier lion learns to roar

A high school reinvents itself with a big pot of money

EDUCATION | Patrick Yeagle

The halls of Lanphier High School are strangely quiet. About 1,100 students file through the school’s maze of corridors several times each day, bringing the usual sounds of slamming lockers, chatty children and a shrill bell announcing the start and end of every period. But absent are certain sounds that used to be common at Lanphier just a couple of years ago: cursing, fighting and open defiance of teachers.

That was the scene during a recent walkthrough of Lanphier by the Illinois State Board of Education, which lauded the progress in turning around what was once considered a dangerous, failing school with help from a large federal grant. Lanphier has struggled with truancy, dropouts, discipline and poor achievement in recent years, but changes to staff, procedures and even the school day itself seem to be making a difference. Attendance is up, achievement is up and discipline appears to be more consistent. While Lanphier still faces major challenges, the school’s teachers, students and parents say the improvement is noticeable. The next challenge will be sustaining the change once the grant money runs out.

The school

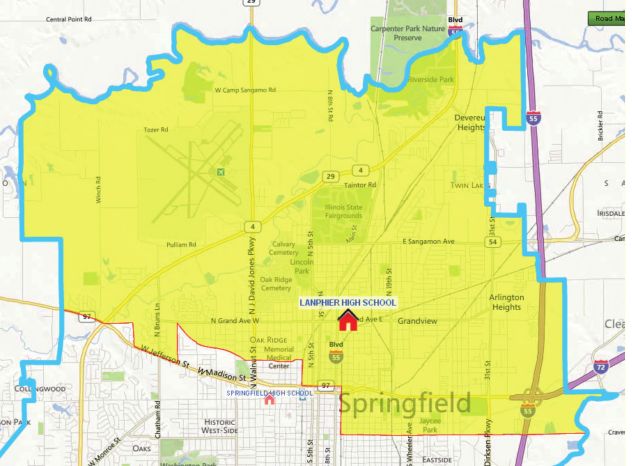

Lanphier sits at the corner of North Grand

Avenue and 11th Street on the city’s north side. The school’s 1,137 students mostly live north of Jefferson Street and Clear Lake Avenue, with part of the school’s southern population boundary extending to Cook Street on the city’s east side.

The school is about 53 percent white and 39 percent black, with small numbers of Hispanic, Asian, Indian and mixed-race students. About 62 percent of the students at Lanphier come from low-income homes, which is slightly higher than the 55 percent at Springfield Southeast High School and far higher than the 35 percent at Springfield

High School. Students from low-income homes tend to score lower on standardized tests, meaning schools with high proportions of low-income students usually post lower scores overall.

Lanphier has been on the state’s “academic watch list” for about nine years, but a 2008 report from the City of Springfield’s Office of Education Liaison and The Springfield Urban League showed the problem of low achievement at Lanphier goes back at least as far as 2001.

Standardized test results from Lanphier show that fewer than half of students meet academic benchmarks for reading and math. The most recent data for 2012 show that only 42.1 percent of Lanphier students met benchmarks for reading, while only 32.2 percent met benchmarks for math. Despite a few years showing improvements, standardized test scores at Lanphier have dropped about 10 points over the past decade. From 2007 to 2011, juniors at Lanphier taking the Prairie

State Achievement Exam performed worse than their counterparts at Southeast High School and at Springfield High School.

The data also show large achievement gaps between white and black students. While 52.6 percent of white students met the reading benchmarks for 2012, only 22 percent of black students met the same benchmarks. Likewise in math, with 41.2 percent of white students and only 10 percent of black students meeting benchmarks.

Lanphier’s graduation rate has decreased each of the past three years, from 89.7 percent in 2009 to only 64 percent in 2012. The graduation rate counts students who earn a diploma in four years or fewer, and it accounts for students who transfer in or out of the school. The current rate of 64 percent is down from a high of 98 percent in 2003. Meanwhile, dropouts increased rapidly from a low of 0.9 percent in 2008 to 5.9 percent in 2011. The most recent data show dropouts declined in 2012 to 4.4 percent.

In addition to the poor

academic performance, the school previously had a reputation for

heavy-handed discipline that accomplished little. During the 2009- 2010

school year, Lanphier administrators handed out nearly 1,300

suspensions, which remove troublesome students from the school but also

increase the number of days those students miss classes, potentially

putting them further behind. Many of those suspensions were for

fighting, using profane language and blatantly defying teachers.

The

poor academic performance and discipline problems at Lanphier over time

created a negative public perception of the school. A history section

on Lanphier’s website bluntly sums up the school’s reputation.

“Many

believe the stereotype that Lanphier is inferior to the other local

high schools,” the website states. “Yet, all students who attend (and

have attended) Lanphier have a strong pride for their school.”

The transformation

Danielle

Cougan is a senior at Lanphier and president of the Student Government

Association. She wants to attend college for business and coach

volleyball. Compared with her freshman year, Cougan says, the school now

holds students to a higher standard, and the quality and depth of

teaching has improved.

“I

feel like we’re getting into deeper learning and teaching from bell to

bell and being on-task,” Cougan said. “It’s higherlevel thinking, more

asking the question ‘why’ and comparing it to events that will happen in

your daily life.”

Ryan Edwards, senior class president at Lanphier, said he has noticed a huge change in the “culture” of the school.

“I

would have to say that the Lanphier of my freshman year is not at all

the same Lanphier that we have today,” Edwards said. “Discipline was a

much larger problem back then. There were kids openly defying teachers

in the hallway. I rarely, if ever, notice that today.”

He

says the school’s half-hour “enrichment” time has helped him learn

about several topics like student loans for college and how to manage

credit cards.

“I’m not

gonna lie: at first enrichment wasn’t the most productive thing in the

world, but come second semester of my junior year, I felt the ACT prep

was very beneficial – especially taking practice tests and stuff,” he

said.

Jessica Pickens

is president of the parentteacher organization at Lanphier, with two

children already graduated from the school and another child who is a

sophomore. Pickens jokingly called herself “that ridiculous parent” who

obsessively checks to make sure her children are doing their homework.

“I

have seen a tremendous change in the discipline,” Pickens said.

“There’s not anywhere near as many fights breaking out. When teachers

say ‘Hey, pull your pants up,’ the students respond. There’s not the

pushback that there was when I first started coming up here three years

ago. There’s definitely a shift and a change. There’s not kids roaming

around now the way there were a couple of years ago.”

Pickens

says communication with teachers has also improved, and parents can now

set up appointments with teachers and administrators quickly.

“Everything

is always very open, and it’s very clear that everyone here is looking

forward to improving things for the students,” Pickens said.

What caused the change? The catalyst was a $5.2 million federal School

Improvement Grant, and the improvements required a lot of

self-examination on the part of Lanphier’s leadership.

The

School Improvement Grant (SIG) is a federally funded grant meant to

help turn around struggling schools. An eligible school is one that has

not made adequate yearly progress for at least two years or is in the

bottom fifth of schools statewide with regard to academic performance.

Lanphier applied for the grant in 2010 and was denied, but the school

applied again and received the $5.2 million grant in 2011.

The

grant money paid for several items like new school supplies and

equipment, for access to online learning and assessment tools, and for

teachers to attend several professional development courses. It also

helped compensate teachers who took on additional duties when Lanphier

extended its school day. At least three new faculty members were hired

with grant money, including Sharon Kherat, Lanphier’s transformational

officer.

Kherat

formerly taught and served as a principal in Peoria public schools, and

at Lanphier she oversees the implementation of the school’s

“transformational plan.” The plan includes increased teacher

accountability, a big push for parent and community involvement in the

school, an early warning system for struggling students, and more

in-depth tutoring to keep those students from failing and

ultimately dropping out. Kherat says Lanphier is focusing on

“empowering” students to do well on their own in the long term.

“We give them a lot of control and ability to get involved in decision making, and then we hold them accountable,” Kherat said.

The

grant-fueled changes seem to be working. During the State Board of

Education visit in December, board members praised Lanphier as being the

highest performing school among all Illinois schools that received the

School Improvement Grant. The school posted an 11 percent gain in

reading benchmarks, and teachers at Lanphier say their students are

becoming better prepared for standardized tests like the ACT.

The

number of suspensions at Lanphier fell below 400 during both the

2010-2011 and 2011-2012 school years, following a change in disciplinary

focus. For the current school year, administrators have given out a

little more than 150 suspensions, which means this year’s total could

come in significantly lower than recent years. Fewer suspensions means fewer

students missing crucial days of class, along with a decreased

likelihood that those students will drop out of school instead of

returning once their suspension is over.

Lanphier

principal Artie Doss says he and his staff specifically focused on

improving discipline at Lanphier with the same approach that Doss used

while principal at Southeast High School and at Springfield Learning

Academy alternative high school.

“The

kids saw that, and they began to buy into it and to like the respect

they were given and that they were able to reciprocate,” Doss said.

Prolonging the change

Prolonging the change

The

efforts to transform Lanphier seem to have been successful so far, but

what happens when the grant money runs out? Doss sums up his hopes in

three words: change of culture.

“As

we look at the initiatives we’ve put in place, we think that we have

sustained a push that has allowed our teachers to grow and our parents

to understand that we’re here to work together,” he said. “Challenges

are still going to be there. We have students coming in at the

ninthgrade level who are behind, and about 50 percent of them are

reading below grade level. So the work and the challenges are going to

continue. But we need to make sure that as we grow, we retain what we’ve

learned, so we can continue to put these practices in place.”

Doss

started as principal at Lanphier in August of 2010. He replaced Shelia

Boozer, who is now principal at Black Hawk Elementary School. The

replacement of Boozer was part of a federally mandated changeup in

administration: any school that receives a School Improvement Grant must

replace the principal and implement several other changes aimed at

improving a school’s leadership – changes like more in-depth

professional development for teachers, a new system of teacher

evaluations and specific efforts to recruit and retain quality staff.

All of those things cost money that won’t likely be available once

Lanphier exhausts its SIG money.

Doss

lauds the work of the teachers and says his staff is already looking

ahead in anticipation of when the grant is exhausted. He says teachers

have started coming up with SLOs – student learning objectives – which

are customized benchmarks created by teachers in their own classrooms to

measure their own students’ progress. The teachers are also creating

their own professional growth plans that will guide their continued

development as instructors. Doss says he and his staff are looking at

other school districts to see how they’ve attempted to maintain momentum

after finishing a grant. He says they’re focusing on how to “sustain

the partnerships we’ve built to move the students forward.”

Partnerships

with parents and the community at large can remain intact without grant

money, given enough deliberate effort, but partnerships with paid

consulting firms and professional development providers cost more than

just time and goodwill. Likewise, equipment and other items already paid

for can continue to benefit students even after the grant ends, but

funding for certain programs and the extended school day will likely dry

up.

Ultimately, the

long-term success or failure of Lanphier rests on the shoulders of its

teachers and staff, who may have to sacrifice time and voluntarily

continue working harder even after the grant is finished. But with

District 186 superintendent Walter Milton and the District 186 School

Board grappling over a tight budget that includes cuts to popular

programs, Lanphier’s transformation could end before it is complete.

“We

know that we can help all students be successful,” Doss says. “The work

continues, and we’ve seen the impact and the growth already. Yet we

know there’s a lot of work to be done.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].